Aaron Stein and Rao Komar

For special access to experts and other members of the national security community, check out new the War on the Rocks membership.

After months of halting and costly progress, the Turkish military and allied Syrian rebels are in a good position to take the Syrian city of al-Bab from the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). With the capture of al-Bab, Turkey will have accomplished the clearly defined goals of its “Operation Euphrates Shield” intervention in northern Aleppo governorate: driving ISIL from the Turkish border and blocking hostile Kurdish forces from linking their territory to Turkey’s south.

But after al-Bab, Euphrates Shield has nowhere to go, and, if Turkey’s gains are to be sustainable, its forces may be unable to leave. With Euphrates Shield, Turkey may have thrown itself into a Syrian quagmire. It has no clear exit strategy and only a poor set of options for escalation. Turkey seems committed to an indefinite but precarious occupation of a piece of northern Aleppo governorate that, perversely, may further weaken Syria’s political and territorial integrity and strengthen Turkey’s adversaries.

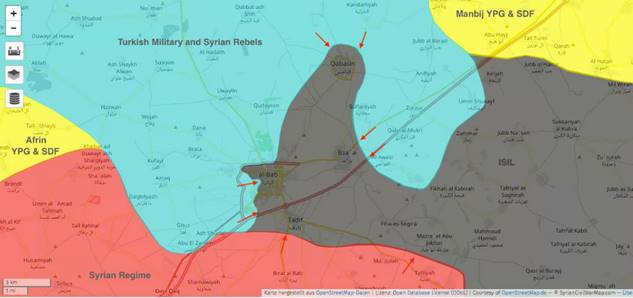

The Syrian regime is poised to take Tadif from ISIL, while al-Bab will likely fall to the Turkish military and Syrian rebels. (SyrianCivilWarMap.com, February 2017)

The Syrian regime is poised to take Tadif from ISIL, while al-Bab will likely fall to the Turkish military and Syrian rebels. (SyrianCivilWarMap.com, February 2017)

Where to After al-Bab?

The Turkish government has not announced a plan to govern the territory it now controls in Syria or to transfer power to a civilian authority capable of administering services in war-torn Syria. Instead, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has recently signaled his intention to expand the operation to target the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the People’s’ Protection Units (YPG). The YPG is the Syrian branch of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the Kurdish-led militia that has waged an insurgent campaign in southeast Turkey since 1984. The YPG also acts as the backbone of the SDF, the United States’ closest partner in the Syrian conflict. This proposal, it seems, is part of a Turkish effort to create a 5,000-square kilometer “safe zone” free of the Islamic State and the YPG. This zone would include both Manbij and Afrin, two well-defended YPG and SDF-controlled areas along the Turkish-Syrian border.

Turkey’s actions after al-Bab falls could have considerable implications for the ongoing American-backed SDF offensive north of Raqqa, the Islamic State’s administrative hub in Syria. A Turkish offensive against Manbij, for example, would force the YPG to move forces from the outskirts of Raqqa, perhaps delaying a planned offensive against the city. The Turkish military could expand its operations after al-Bab, but its potential adversaries are prepared to defend against a Turkish-backed assault. The defenses are similar to those that have slowed Turkey’s operations around al-Bab, risking another set of bloody battles for Syrian cities without any coherent mechanism to govern and then withdraw from territory taken.

The risks of a prolonged Turkish occupation are considerable. Turkey’s difficulties around al-Bab have also allowed for the Syrian Arab Army and allied militias, backed by Russian airstrikes, to push east from Aleppo City. The Syrian Arab Army and its allies are now in control of the high ground overlooking the main road connecting al-Bab with Raqqa, effectively blocking any Turkish offensive toward Raqqa. At the time of writing, the Turkish and Syrian armies appear to be pushing to take the same city, Tadif, although Russia may have succeeded in brokering a ceasefire along the dividing line between northern Tadif and the southern entrance to al-Bab.

Turkey and its rebel allies are slowly advancing in al-Bab, and will eventually push ISIL out of the city. To the south, regime forces have pushed towards Tadif and have cut the al-Bab/Raqqa road, rendering a Turkish offensive towards Raqqa unlikely. (SyrianCivilWarMap.com, February 2017)

Turkey and its rebel allies are slowly advancing in al-Bab, and will eventually push ISIL out of the city. To the south, regime forces have pushed towards Tadif and have cut the al-Bab/Raqqa road, rendering a Turkish offensive towards Raqqa unlikely. (SyrianCivilWarMap.com, February 2017)

The division of territory has temporarily calmed tensions around the city, but the reality is that Turkish forces and a coalition of loosely aligned proxy militias now share a frontline with the Syrian regime, embedded Russian advisers, and Alawite militias. These two fractious coalitions are now within mortar range of one another, a state of affairs that is inherently destabilizing.

Further still, the regime’s advance south of al-Bab limits Turkey’s options and all but rules out any potential Turkish plan to expand Operation Euphrates Shield to push south toward Raqqa. Ankara had previously touted this proposal to U.S. officials and to the international media as an alternative to a SDF-led offensive for the ISIL-held city. Now, Turkish forces could only do this if they were willing to fight through the Russian-backed regime positions to the south of al-Bab and then come back into contact with ISIL on the outskirts of Raqqa. As this would trigger open war with the Syrian regime, it seems like an unlikely path for Turkey. Instead, Turkish forces could still seek to expand operations around Tel Rifaat or Manbij, two cities Turkey has occasionally pledged to target as part of Euphrates Shield.

The Tel Rifaat Offensive: Turkish Options and Limitations

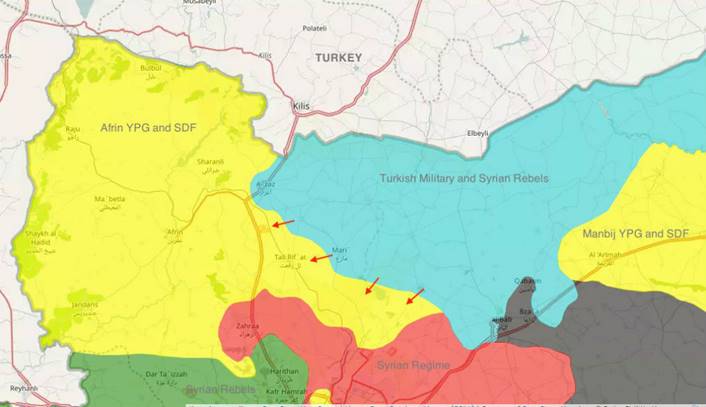

In the northwest of Syria, the YPG holds the Afrin canton, a mountainous and largely Kurdish area abutting the Turkish-held territory in Syria. One option, often floated by Syrian rebels and the Turkish government, is an assault on the YPG in Afrin to capture Tel Rifaat, an Arab-majority town near the western border.

A rebel offensive on Tel Rifaat (Tall Rif’at) in Afrin would involve an attack along the entire frontline south of A’zaz. (SyrianCivilWarMap.com, February 2016)

A rebel offensive on Tel Rifaat (Tall Rif’at) in Afrin would involve an attack along the entire frontline south of A’zaz. (SyrianCivilWarMap.com, February 2016)

Tel Rifaat has been under YPG control since February 2016, when the group captured it from rebels with the support of the Russian and Syrian air forces. The Syrian rebels are therefore motivated and willing to fight the YPG in this area. The Turkish military and its rebel allies have clashed with YPG in the past around Tel Rifaat. On October 22, 2016, Free Syrian Army factions, backed by Turkish air and artillery strikes, began their assault on the town, but were pushed back. Three days later, Turkish-backed rebels lost two villages southeast of Tel Rifaat to a YPG counterattack.

Unlike the rebels of Operation Euphrates Shield, who have been constantly fighting ISIL since March 2016, the YPG in Afrin is well-rested and has largely not been involved in the grueling back-and-forth civil war. Turkish-backed rebels have a manpower deficit. They are heavily dependent on poorly trained fighters recruited from Syrian refugee populations in Turkey, local fighters from northern Aleppo, and some rebels who moved from Idlib. While these manpower sources would be appropriate for administering a smaller sized territory, they have been significantly depleted by the recent internecine conflict in Idlib and years of battle with ISIL and the Syrian regime. This manpower deficit would complicate any attack on Tel Rifaat. With over 175 kilometers of militarized frontline to defend, Syrian rebels would have to mass their forces in one area for an offensive without leaving other frontlines dangerously undefended from an Islamic State counter attack, SDF forces outside of Manbij, or regime forces south of al Bab. The Afrin YPG has a much shorter frontline to defend, so they can bring more forces to bear if needed.

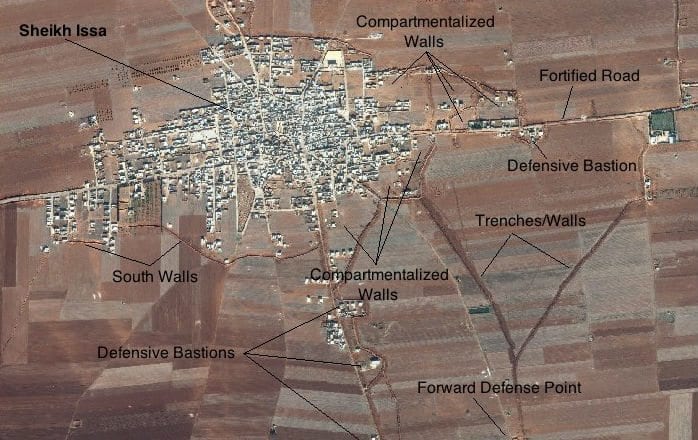

The YPG has been expecting a rebel offensive to retake Tel Rifaat ever since it captured the town in early 2016. The YPG and its SDF allies have spent over a year building up defensive fortifications, such as earthen berms, checkpoints, and trenches. Afrin now has some of the most extensive defensive fortifications seen in northern Syria, similar to those ISIL employed to great effect to slow the Turkish-backed offensive on the al-Bab’s western entrances.

A satellite image of the defenses surrounding Sheikh Issa, one of the satellite towns that Euphrates Shield would have to take before reaching the Tel Rifaat defensive lines. (Terraserver, November 2016)

A satellite image of the defenses surrounding Sheikh Issa, one of the satellite towns that Euphrates Shield would have to take before reaching the Tel Rifaat defensive lines. (Terraserver, November 2016)

Tel Rifaat’s extensive defensive network, consisting of a web of walls and fortified towns, would impose costs on advancing Turkish forces, risking a prolonged campaign to take the city. With the Afrin YPG, Russia, and the Syrian regime in a tacit alliance, Turkey and its rebel allies may end up facing off with YPG ground forces backed up by two air forces if they attack and risk escalation with Russia or the Syrian regime. Russia and the regime have already demonstrated a commitment to use force in the area, even when Syrian troops are within mortar range of Turkish soldiers. A Russian airstrike killed 3 Turkish soldiers in February, while a second strike, attributed at various times to Russian, regime, or Iranian air assets, also killed Turkish soldiers operating near al-Bab in late November 2016.

Consolidating the Eastern Flank: Options for Manbij

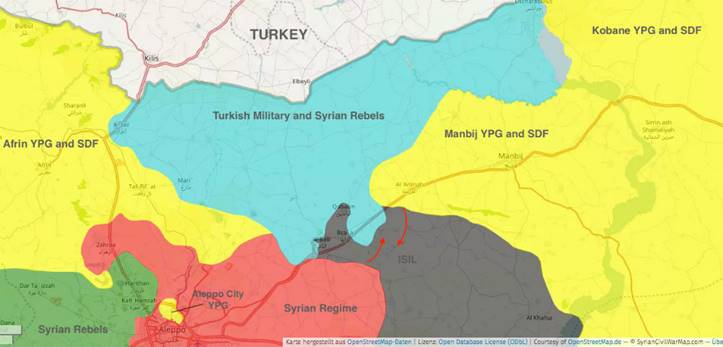

South of al-Bab, the Syrian regime, backed by Russian airstrikes, have advanced to within 1.5 kilometers of the city. Regime forces now share a 10 kilometer-long frontline with Turkish-backed forces on the city’s southwestern outskirts. This Syrian move threatens to link its frontline just south of Tadif with SDF-held positions west of Manbij, potentially creating an alternative route to link SDF-held territory with Afrin, south of al-Bab. This would undermine the intended goal of Euphrates Shield of preventing the formation of a contiguous Kurdish region in Syria. The Syrian regime could use this as a point of leverage with the YPG in future peace negotiations, and Russia is working to facilitate this course of action with various Kurdish and regime interlocutors.

The Syrian Regime and the Manbij YPG could easily launch a coordinated offensive against ISIL, cutting off Turkey’s route for expansion. With this, the YPG could effectively connect Manbij to Afrin using Syrian regime territory following Russian-facilitated negotiations with the regime. (SyrianCivilWarMap.com, February 2017)

The Syrian Regime and the Manbij YPG could easily launch a coordinated offensive against ISIL, cutting off Turkey’s route for expansion. With this, the YPG could effectively connect Manbij to Afrin using Syrian regime territory following Russian-facilitated negotiations with the regime. (SyrianCivilWarMap.com, February 2017)

To prevent this, Turkey could choose to launch an offensive against SDF territory to the east of rebel-held northern Aleppo governorate. The end goal of such an operation would be to take Manbij, a city that the SDF, backed by U.S. airstrikes and special operations forces, captured from ISIL after a nearly three month-long battle and siege in summer of 2016.

Turkey has fought the SDF in this area before. At the start of Euphrates Shield, the Turkish and rebel forces rapidly pushed the YPG and their SDF allies back north of the Sajur River in a surprise offensive. With the Sajur River forming a natural boundary between the Manbij YPG and the Euphrates Shield forces, an American-backed ceasefire was put in place and has worked to minimize violence along the tense front line.

Some three months later, the situation has changed significantly. The YPG and SDF have dug in and fortified their positions, so Turkish armor and rebel infantry will not be able to rapidly advance as they did at the start of the operation. Political considerations also play a role in making a large-scale Turkish operation against the YPG in this area unlikely. Unlike the Afrin YPG, who cooperate extensively with the Syrian regime and Russia, the YPG and SDF in this region have a close working relationship with the United States and shared goals of pushing ISIL out of northern Syria.

To the east of the Euphrates River and Manbij, the YPG and its Arab allies in the SDF are preparing for an operation targeting Raqqa. American support in the form of arms, air support, and embedded special operations forces will be key to the capture of the city, but the operation is expected to rely heavily on local Syrian Kurdish and Arab forces.

A Turkish-led attack on Manbij would slow the Raqqa operation, as YPG forces would likely move from Raqqa to defend the frontlines in Manbij. Turkish President Erdogan has sought to offer an alternative option for taking Raqqa that would involve Euphrates Shield forces, rather than the Kurdish YPG and Arab SDF. However, the Turkish military and its allied rebels have struggled to capture al-Bab, a city with a pre-war population of only 63,000. Raqqa is nearly four times larger and sits some 180 kilometers south of the current Turkish-held frontline. An offensive against it would require more troops and more complicated and exposed logistical chain, independent of the capabilities of the local partners.

Turkey has one other option: It could invade Tel Abyad, an SDF-held town. Turkey will retain this option indefinitely, but actually pursuing it would entangle Turkish military forces on third front in Syria’s multi-sided civil war. Moreover, taking territory from Kurdish forces in Tel Abyad would likely boomerang back into Turkey, resulting in cross-border YPG attacks against various Turkish targets along the border.

Turkey’s final option is to launch a major military operation on Tall Abyad, clearing out the YPG and SDF, then proceeding to Raqqa. This option will lead to open warfare between the YPG and the Turkish government along the Syrian border and would be a major escalation of Turkish involvement in Syria. (SyrianCivilWarMap.com, February 2017)

Turkey’s final option is to launch a major military operation on Tall Abyad, clearing out the YPG and SDF, then proceeding to Raqqa. This option will lead to open warfare between the YPG and the Turkish government along the Syrian border and would be a major escalation of Turkish involvement in Syria. (SyrianCivilWarMap.com, February 2017)

Boxed In: So, Now What?

The Turkish government has repeatedly stated that it does not intend to stay in Syria in the long term. However, a premature withdrawal may leave the Euphrates Shield rebels weak and ill-equipped to deal with threats from the YPG or the Syrian regime, both of whom have clashed with the rebels in the past.

Prior to the Turkish intervention, the rebels that now constitute Euphrates Shield struggled to defend territory against ISIL attacks. They were nearly wiped out in an ISIL offensive on the city of Marea in the 2016. The Turkish forces will have to reorganize the rebel forces, currently split into dozens of factions, into a force that can independently defend its territory.

Turkey faces a similar problem as other professional militaries that work with local partners to take territory on the battlefield. Tensions between Islamist rebels and less conservative Free Syrian Army factions have often resulted in tit-for-tat kidnappings. Increasingly, internecine warfare breaks out over control of trade revenues and smuggling in Turkish-held territory in Syria. Some Turkish citizens, members of Turkish nationalist groups, have joined the rebel fray in Syria, creating tensions between the conservative and often Arabized Syrian Turkmen and the less religious nationalist Turkish volunteers. The Turkish military presence in Syria has suppressed these tensions for the most part, but they are likely to return once the Turkish military withdraws.

In addition to reorganizing the rebels into an independent and effective fighting force, Turkey faces the challenge of supporting the creation of a unified governing structure across the northern Aleppo governorate rebel territory. Currently governance in the area is split between a mishmash of disconnected and often conflicting sharia courts, civilian-led city councils, rebel militias, and Turkish forces, all operating with little overarching framework. Turkey will have to turn its attention to building institutions to govern the northern Aleppo territory, a slow and complex process with no clear timeframe. Turkey will therefore have to consolidate control over territory taken, regardless of the military choices it makes, either near Tel Rifaat or Manbij.

The consolidation of Turkish-backed governing bodies, while necessary to create the conditions to withdraw, may also contribute to an outcome Ankara has worked to prevent: the decentralization and devolution of the Syrian state, as regional institutions are strengthened at the expense of the central government. This outcome would also help to strengthen the case for empowered local regions, which would benefit the Syrian Kurds’ political aspirations. That said, the decentralization of the Syrian state may now be inevitable regardless of Turkish action.

Turkey will soon achieve its narrowly defined military objective: the defeat of ISIL in al-Bab to ensure that Kurdish-held territory along the Turkish-Syrian border will not be connected. Yet the challenges will persist as Turkey moves to a different phase of operations: state-building. This will create another set of issues to deal with that guarantee Turkish presence in Syria for the foreseeable future.

A special thanks to SyrianCivilWarMap.com for providing maps for this article.

Aaron Stein is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East

Rao Komar (@RaoKomar747) is an Austin based journalist and Middle East/Eurasia analyst.

Bir yanıt yazın