Confused may be an appropriate term to describe Turkey’s current foreign policy in the Middle East and Israel in particular. The source of that confusion — aside from the appalling violence in Syria and earlier in Libya — is Turkey’s own range of mistakes.

The Turkish government’s inconsistency regarding Israel highlights earlier discrepancy in other political contexts. There was a time when Turkey’s top foreign policy priority included reaching out diplomatically to Arab and Muslim countries. Then, we spoke of a paradigm shift, whereby Istanbul was repositioning its political center, reflecting perhaps economic necessity, but also cultural shifts within its own society. It seemed that the East versus West debate was skillfully being resolved by politicians of the Justice and Development Party (AKP).

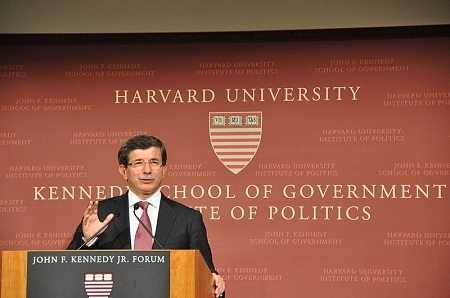

The ‘Zero Problems’ policy

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, along with Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, appeared to have obtained a magical non-confrontational approach to Turkey’s historic political alignment. “The Zero Problems” policy allowed Turkey to brand itself as a bridge between two worlds. The country’s economic growth and strategic import to various geopolitical spheres allowed it to escape whatever price was meted out by Washington and its European allies as a reprimand for its bold political moves — including Erdogan’s unprecedented challenge of Israel.

Indeed, there was a link between the growing influence of Turkey among Arab and Islamic countries and Turkey’s challenge to Israel’s violent behavior in Palestine and Lebanon, and its rants against Syria and Iran. Turkey’s return to its political roots was unmistakable, yet interestingly, it was not met by too strong an American response. Washington couldn’t simply isolate Istanbul and the latter shrewdly advanced its own power and influence with that knowledge in mind. Even the bizarre anti-Turkish statements by Israeli officials sounded more like incoherent rants than actual foreign policy.

Israel’s clout in the region

Political arrogance and U.S.-financed military strength are two pillars by which Israel maintains its clout in the region. The first was childishly applied when the then Israeli Deputy Foreign Minister, Danny Ayalon, publicly snubbed Turkey’s Ambassador, Ahmet Oguz Celikkol, in January 2010 by placing him on a lower sofa. He then asked Israeli journalists to take note of the insult. The second came in May 2010 when Israeli commandos descended on the Turkish ship Mavi Marmara, carrying humanitarian aid to Gaza, and killed nine Turkish citizens in cold blood.

“Idiocracy” is how Israeli columnist Uri Avnery described Israel’s behavior toward Turkey, which was once one of Israel’s most vital allies. But idiocy has little to do with it and Turkey knew that well. Israel wished to send strong messages to the Turks, that its strategic and political maneuvering was of no use here and that Israel would continue to reign supreme in the face of Erdogan’s ambitious policies. The real idiocy was Israel’s miscalculations, which failed to take into account that such behavior could only speed up Turkey’s political transformation. The fact that the U.S. was losing its once unchallenged grip over the fate of the Middle East had also contributed to Turkey’s sudden rise as a country with far-reaching ties and long-term political vision.

Turkey’s new political priorities

Erdogan quickly rose to prominence. His responses to Israel’s provocations, and to what was essentially a declaration of war, came in the form of strong words and measured actions. He conditioned any rapprochement with Israel on a clear apology over its transgressions, compensations to the victims and the families of the dead, and ending the siege on Gaza. The last condition further highlighted Turkey’s new political priorities.

As far as Turkey’s regional ascendency was concerned, it mattered little whether Israel apologized. Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was losing favor, even with his own allies in Washington. And unlike Washington, under the thumb of the pro-Israeli lobby, Istanbul was a country with independent foreign policy.

The Turkish government’s inconsistency regarding Israel highlights earlier discrepancy in other political contexts. There was a time when Turkey’s top foreign policy priority included reaching out diplomatically to Arab and Muslim countries

Ramzy Baroud

When AKP triumphed in Turkey’s elections in June 2011, the so-called Arab Spring was still in its early stages. Then, much hope was placed on the rise of popular movements in countries that have been disfigured by Arab dictators and their Western benefactors. Not only did the ruling party disregard the fact that Turkey had taken part in the old political structure in the Middle East, it also escaped them that Turkey was an important member of NATO which unleashed a terrible war on Libya on March 19, deliberately misinterpreting U.N. Security Council Resolution 1973. Yes, Turkey had resisted the war option at first, but it was quick to forgive and forget and eventually recognized and supported its political outcome. Thanks to the war, Libya is now in a permanent state of bedlam.

Victory Speech

Erdogan’s victory speech in June 2011 attempted to paint a new picture of reality regarding future prospects and Turkey’s proposed role in all of this. “I greet with affection the peoples of Baghdad, Damascus, Beirut, Amman, Cairo, Tunis, Sarajevo, Skopje, Baku, Nicosia and all other friends and brother peoples who are following the news out of Turkey with great excitement,” Erdogan said. “Today, the Middle East, the Caucasus and the Balkans have won as much as Turkey.”

But that “win” was short-lived. The euphoria of change created many blind spots, one of which is that conflicts of sectarian and ethnic nature — as in Syria — don’t get resolved overnight; that foreign military intervention, direct or by proxy, can only espouse protracted conflict. Indeed, it was in Syria that Turkey’s vision truly fumbled. It was obvious that many were salivating over the outcome of a Syrian war between a brutal regime and a self-serving, divided opposition, each faction espousing one foreign agenda or another. Suddenly, Turkey’s regional and global ambitions of justice and morality grew ever more provisional because of fear of chaos spilling over into its border areas, the tragic rise of the number of Syrian refugees at Turkey’s borders and the fear of a strong Kurdish presence innorthern Syria.

Erdogan: ‘Israel a terrorist state’

Not even capable Turkish politicians could hide the confusion in which they found themselves. Responding to Israel’s bombing of Gaza last November, which killed and wounded hundreds of Palestinians, Erdogan described Israel as a “terrorist state.” “Those who turn a blind eye to discrimination toward Muslims in their own countries, are also closing their eyes to the savage massacre of innocent children in Gaza. … Therefore, I say Israel is a terrorist state.”

But even then, discussions were under way regarding the text of an Israeli apology to Turkey over the Mavi Marmara attack. That apology had finally arrived as an undeserved gift to U.S. President Barack Obama, who visited Israel in March with a message of total support for Israel.

“In light of Israel’s investigation into the incident which pointed to a number of operational mistakes, the prime minister expressed Israel’s apology to the Turkish people for any mistakes that might have led to the loss of life or injury and agreed to conclude an agreement on compensation/non-liability,” Netanyahu’s apology read. No commitment regarding Gaza was made. Erdogan’s office responded: “Erdogan told Benjamin Netanyahu that he valued the centuries-long strong friendship and cooperation between the Turkish and Jewish nations.” According to Netanyahu, the apology over the “operational mistakes” had everything to do with the need to share intelligence over Syria between both of the countries’ militaries. To balance out Turkey’s hurried retreat to its old political foreign policy, Erdogan is reportedly planning to visit Gaza in April.

“We will take on a more effective role. We will call, as we have, for rights in our region, for justice, for the rule of law, for freedom and democracy,” were the resounding words of Erdogan following his party’s elections victory last year.

It is likely that Istanbul will try to maintain a balanced position, but, as Erdogan himself knows, in issues of morality and justice, middle stances are simply untenable.

_____________

Palestinian-American journalist, author, editor, Ramzy Baroud (www.ramzybaroud.net) taught Mass Communication at Australia’s Curtin University of Technology, and is Editor-in-Chief of the Palestine Chronicle. Baroud’s work has been published in hundreds of newspapers and journals worldwide and his books “His books “Searching Jenin: Eyewitness Accounts of the Israeli Invasion” and “The Second Palestinian Intifada: A Chronicle of a People’s Struggle” have received international recognition. Baroud’s third book, “My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story” narrates the story of the life of his family, used as a representation of millions of Palestinians in Diaspora, starting in the early 1940’s until the present time.

Gaziantep, sixth largest city in Turkey, has been one of the biggest losers from the Arab uprisings

Gaziantep, sixth largest city in Turkey, has been one of the biggest losers from the Arab uprisings Turkey shares an 800km-long border with Syria

Turkey shares an 800km-long border with Syria Turkish officials have explained that they had no choice but to back the Syrian opposition

Turkish officials have explained that they had no choice but to back the Syrian opposition Gaziantep’s factories are exploring alternative export routes and markets for their products

Gaziantep’s factories are exploring alternative export routes and markets for their products