Lucien Arkas, chairman of Arkas Holding A.S., discusses his LA Wines property at Swissotel Grand Efes in Izmir. Arkas bought out his partners in 2010, renaming it LA Wines. Its vineyards are now certified organic. Photographer: Elin McCoy/Bloomberg via Bloomberg

At a tasting in a World War II cement bunker in Gali winery’s vineyards on Turkey’s Gallipoli peninsula, the 2010 bright, juicy cabernet franc-merlot blend is a big and very pleasant surprise.

One of several dozen small boutique wineries founded in the last few years, Gali is part of the country’s growing wine renaissance. It was the first stop on recent tasting tour that left me highly enthusiastic about Turkey’s wine potential.

After tramping through Gali’s vineyards, with windy views of the blue Aegean Sea, the Dardanelles and Sea of Marmara, I savor the delicious red again on owner Hakan Kavur’s stone terrace with oregano-accented lamb slow-braised in local olive oil.

When it comes to wine, you’re never far from history in this country of more than 800 grape varieties. Though many new vintners in Turkey’s seven wine regions champion international ones like chardonnay and cabernet, I discover the best wines so far come from a handful of Turkish grapes with hard-to-pronounce names like okuzgozu (oh-cooz-goe-zoo) and kalecik karasi (kah- le-djic-car-ah-ser).

Indiana Jones

The centerpiece of my 10-day trip is the EWBC Digital Wine Communications Conference in Izmir on the Aegean. One of the main speakers, Patrick McGovern of the University of Pennsylvania Museum — who is called the Indiana Jones of wine archeology — makes the case for Turkey as wine’s birthplace.

His presentation covers the country’s several thousand years of flourishing drinking culture under the Hittites, Assyrians, Lydians and Byzantine Christians.

Despite that history, Turkey’s 100-plus wineries face serious challenges in a land with a 99 percent Muslim population. The government discourages consumption through high taxes and advertisement bans, and this year prohibited internet sales.

None of that stopped Izmir native Lucien Arkas, chairman of Arkas Holding A.S., owner of 55 companies, and a major art collector, from investing in a 1,168-acre property 45 minutes southeast of Izmir.

As we talk over small glasses of Turkish tea in between the conference’s panels and tastings, Arkas, 67, smiles and shrugs, “People still smoke and drink. Twenty million tourists want to go to the beach, and sip wine.”

LA Wines

The genial, round-faced Arkas, in a dark blue Zegna suit, says he purchased a small share in the 2005 project sight unseen, but bought out his partners in 2010. Now the vineyards are certified organic, and he renamed the winery LA Wines.

I like LA’s pure-tasting 2010 Mon Reve chardonnay/chenin blanc ($16), with its hint of pears and tropical fruit, and the earthy 2010 Mon Reve Tempranillo. I sip them at the Arkas museum in Izmir, while studying Turkish photographer Ahmet Ertug’s stunning pictures of European opera houses and libraries.

Like Kavur, Arkas is wedded to European grape varieties rather than his country’s own.

Happily, both avoid the excessive-oak-aging embraced by many of Turkey’s small estate wineries. Case in point: The Gulor winery founded in 1993 by Guler Sabanci, the chairman of her family’s Sabanci Holding (SAHOL), the second largest company in Turkey, and the first to plant international grapes. Gulor makes a clean, fresh 2012 G Sauvignon Blanc ($11), but its pricier reds taste more of wood than fruit.

Local Grapes

Some of the biggest (and oldest) wineries are now refocusing on indigenous grapes. Doluca dates from 1926, and at its huge new modern cellar hidden away in a vast gray industrial park a 90-minute drive from Istanbul, its French winemaker Pascal Lenzi pours barrel samples of a crisp, lemony white 2012 Narince (nah-rin-djeh) and a lively easy-drinking 2012 Kalecik Karasi, the Turkish answer to gamay, the grape of Beaujolais.

But a few days later, on the high desert plateau of Cappadocia in central Anatolia, I find the most exciting wines of my stay at the traditional Kocabag winery outside Uchisar. The spare, windswept expanse of landscape, where herds of wild horses once roamed and patches of grapevines sprawl like low bushes as they did thousands of years ago, seems vast and timeless.

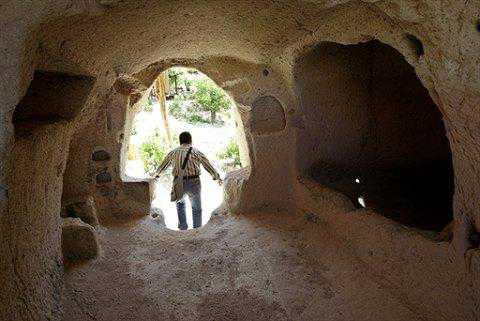

“My grandfather started in 1972 in a simple cave carved from rock,” explains third generation Mehmet Erdogan, as he leads the way into the winery. The stone arches and fermenting and aging vats are all carved from soft, easy-to-work tuff rock made of compressed volcanic ash.

Lamb Kebab

At a wine bar and shop overlooking the strange rock formations in Uchisar’s Pigeon Valley, Erdogan pours Kocabag’s two whites and three reds.

My white pick is tart, appley 2011 Narince, with its floral aromas and wet stone taste. Among reds, the stars are 2011 Kapadokya ($14), a complex earth-and-black-cherry blend of bogazkere and okuzgozu and the subtle, soft cassis and fruit 2010 Okuzgozu ($16), which is perfect with lamb shish kebab. I had to have a second glass.

(Elin McCoy writes on wine and spirits for Muse, the arts and leisure section of Bloomberg News. The opinions expressed are her own.)

Muse highlights include Jeremy Gerard on theater and Martin Gayford on art.