KONYA, Turkey — The anniversary of the death of Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi, the 13th-century Sufi poet who died in 1273, took place on Dec. 17. Nowhere is this more evident than in this south-central Turkish city, which draws thousands of tourists each December to see the most important Whirling Dervishes ceremonies.

You might be hard-pressed otherwise to find many parties in this religiously conservative city. The fact that Konya’s biggest festivities honor someone’s death speaks volumes. On Saturday nights, you are more likely to find people hanging out at barbershops than at bars.

If you go

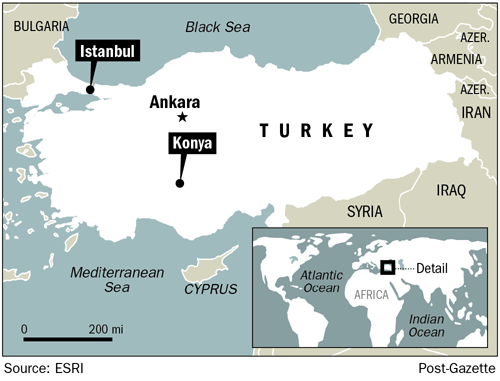

For a trip to Turkey, Istanbul is the best entry point. Turkish Airlines flies direct from New York or Washington, D.C., although other airlines fly through Europe.

From Istanbul, flights to Konya and cities in central Turkey are inexpensive, and a trip to Konya would be well paired with a few days spent in nearby Cappadocia, famous for its cave churches, underground cities and unusual landscape best seen from a hot air balloon.

It is less glamorous than Turkey’s more popular tourist destinations of Istanbul, with its elaborate architecture; Bodrum, with its pristine beaches; and Cappadocia, with its caves. But as the city in Turkey where Rumi (known as Mevlana in Turkish) spent much of his life after moving from Persia, Konya gets to play host to the Mevlana Festival every year (Dec. 10-17), when the Whirling Dervishes — members of the Mevlevi Order that follow his teachings — give their most famous ceremonies at the Mevlana Cultural Center.

My weekend trip to Konya to see the dervishes was well worth the visit — not merely for the dervish ceremonies that occur regularly throughout the year and the special December performances but also for Konya’s other offerings. The museums, featuring ancient artifacts, Mevlana’s relics and centuries-old handicrafts, are understated but rich; most important, they reveal a depth and tradition unrivaled in most places, and a window into the regular lives of people who lived thousands of years ago.

I am in Istanbul for 10 months on a post-college traveling fellowship to study Turkish music and didn’t want to miss the festival. I had made arrangements with my friend Bekir, whom I met last summer while interning at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, to stay with his extended family in his brother’s apartment in Konya.

Bekir’s father secured a ticket to the Saturday afternoon Whirling Dervishes ceremony for me. The biggest ceremony occurs Dec. 17, but tickets to that event are especially difficult to come by.

Besides these arrangements, I did not know what to expect. I knew that Bekir’s family spoke only Turkish, and I spoke very little. As a secular American, I was coming to stay with a family in a city known for its faith.

Bekir’s parents met me at the airport on Dec. 14. His father was holding a sign that read “Liz.” We walked to his car, where Bekir’s head-scarfed mother eagerly welcomed me, holding my hand, and chatting quickly in Turkish. When I understood anything she said — a rare occurrence — I would excitedly respond, Evet, meaning “Yes.” I would get good practice on my Turkish throughout the weekend, especially with the word Anlamiyorum, meaning, “I don’t understand.”

When we arrived at the apartment, Bekir’s mother and I shared Turkish tea and cornflakes. I understood the universal motherly insistence on taking food, and grabbed a few handfuls. We tried our best at conversation; she thumbed prayer beads. The other members of Bekir’s extended family — young nieces and nephew, sister-in-law, and brother — started coming home for the evening.

I was anxious to see what the weekend would hold.

While the festival particularly commemorates Mevlana’s death, the Whirling Dervishes (sema) ceremony also represents a mystical journey of man’s ascent through mind and love to “Perfect,” according to a website operated by Mevlana’s descendants. Whirling toward truth, he deserts his ego; and he returns from this spiritual journey having reached maturity and greater perfection, so as to love and to be of service to the whole of creation. (The ceremony on Dec. 17 — the anniversary of Mevlana’s death — is his “wedding night” with God).

At more than seven centuries old, the ceremony in December was a mix of old and new; advanced lighting technicians splashed blue and green and yellow hues onto the circular stage. The accompanying orchestra included traditional Turkish instruments, such as a kemenche, a Turkish violin played vertically, and a ney, a wooden flute.

A vocalist began singing; his voice was guttural and throaty, and amazingly controlled, like the ney in the orchestra. His voice bent, nasal, fluttering, using notes and motions foreign to American music.

The dervishes, all men, entered the stage wearing black robes and hats. The tall hats represent the tomb for the ego, according to the website. Early in the ceremony, the dervishes removed the black robes, revealing white robes with skirts (the shroud for the ego). The audience, meanwhile, wore no special attire — jeans, or headscarves. To music from the orchestra, they gathered in pairs; they bowed to each other; they whirled, pivoting their right foot around their left. They held up their hands, one hand pointed to heaven, the other to earth. Their heads cocked, their skirts swaying in and out, they moved counterclockwise, twirling like well-trained figure skaters.

I wondered whether they got dizzy. The effect was simultaneously mesmerizing and calming. They moved between the whirling, the pairing, and the bowing, for about an hour.

At the end of the two-hour ceremony, the dervishes put their black robes back on. The vocalist sang anew. Together, the audience joined in singing a prayer, lifting their hands, a community brought together by the ceremony. It was not merely a spectacle.

Bekir’s cousins, all under the age of 15, were eager to show me their English books, “The Berenstain Bears” and “The Little Engine That Could” among them. They pelted me with basic questions in English, about my favorite color and sport and so on. Deeper questions would require a combination of my broken Turkish and Google Translate. They asked me about my religion, about whether I drank and I ate pork, before our delicious Turkish dinner of borek (cheese pastry), yogurt soup, beans, meat and bread.

After-dinner festivities involved watching YouTube videos with the cousins, to both Turkish and non-Turkish songs, such as PSY’s “Gangnam Style.” They told me they liked President Barack Obama, but didn’t like former President Bill Clinton or President George W. Bush; they really liked Turkey’s Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan, the head of Turkey’s ruling conservative AK Party. At 11 p.m., the children brought out an enormous picnic for us, blanket and all. We sat on the floor to eat salted and sugary chickpeas, sunflower seeds, figs, fresh fruit and pistachios.

After being overfed (a common condition in Turkey), I went to bed, stuffed by food and warmth, humbled by my host family’s hospitality.

Besides the Whirling Dervishes ceremony, my favorite sites in Konya were the Mevlana Museum and the Archaeology Museum.

The crowded Mevlana Museum, which serves as a mausoleum and as a former lodge for the Whirling Dervishes, had magnificent collections illuminating both ordinary and extraordinary lives. Rumi’s massive tomb and clothes juxtaposed a collection of old Qurans stretching back to the ninth century. A clipping of Muhammad’s hair sat in a display case, which has a small hole through which museum-goers eagerly smelled the hair of the Prophet.

At the Archaeology Museum we were the first to arrive, a few minutes after 11 a.m. It looked closed; the operator opened it up for us and turned on the lights. He let me take photographs.

The collection was full of objects thousands of years older than anything I had seen at home in America, excavated from local archaeological sites. Tombs from Roman times, a bath from the Assyrian Colony period (1950-1750 B.C.), a human skull from 6300 B.C., cups and pots and lamps and wine vases for the thousands of years in between.

We spent an hour in this museum. Most of the museums we visited were small, requiring fewer than 20 or 30 minutes to browse, and admission cost just a few dollars. Among them, they gave a glimmer of what life was like centuries or millennia ago.

After attending the ceremony, I joined Bekir’s extended family for dinner at Akyokus Park, a large restaurant atop a hill, with a view of Konya. I ate firin kebabi, soft meat on top of flat bread.

After dinner, as we had done the previous night, we stayed up late with the extended family at another sister’s apartment, talking and dancing to videos. The adults asked me about my religion, how I prayed, whether there were Muslims in America. The children (myself included) wore costumes for photographs and role-plays. Upon returning home, we stayed up until 2 a.m., discussing Turkish and American politics, with Google Translate’s help.

I bid Bekir’s family farewell on Sunday at the airport. We connected on Facebook, and they invited me back to their home. Their hospitality far exceeded anything I could have had the audacity to expect. I will always remember their warmth and openness to a barely Turkish-speaking American — someone who was radically different from them, but who could share conversation and humanity over Turkish tea.

In all, Konya, through its museums and ceremonies showed me the stuff of ordinary life, in lives radically different from mine, from thousands of years ago — how they drank, bathed, played music, decorated, buried their dead. Many of those customs continue today.

It was a brief window into an entirely foreign world. Indeed, it’s worthwhile to understand how others far removed from your ordinary life live their ordinary lives.

First Published January 20, 2013 12:00 am