July 28, 2010

On Tuesday, July 28, Director of the Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center, Ross Wilson, spoke at a hearing of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, entitled “Turkey’s New Foreign Policy Direction: Implications for U.S.-Turkish Relations.” Soner Cagaptay, Director, Turkish Research Program at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Ian Lesser, Senior Transatlantic Fellow, the German Marshall Fund of the United States; and Michael Rubin, Resident Scholar, American Enterprise Institute, also testified.

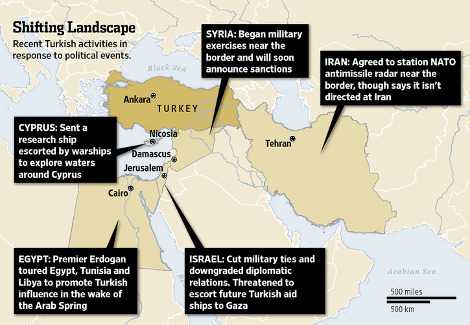

Recent tensions over Iran and Israel have called into question the direction of Turkey’s orientation and especially its role in the Middle East. Ambassador Wilson acknowledged recent problems, urged these developments be viewed in the context of an overall relationship that had important strategic benefits, and emphasized the imperative of more effective engagement of Turkish leaders and public opinion on Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, the Middle East and other issues.

Turkey and the United States: How To Go Forward (and Not Back)

Statement for the Record

Ross Wilson

Director, Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center

Atlantic Council of the United States

July 28, 2010

House Committee on Foreign Affairs

Mr. Chairman, thank you very much for the honor of being invited to speak at this hearing on Turkey and U.S. Turkish relations.

Turkey is a fascinating, sometimes frustrating, often confusing and very important country in a key part of the world for the United States. Figuring it out is a challenge. It is tempting, but always misleading, to see black and white where grays are the dominant colors. One of the most useful observations I heard while I had the honor to serve as American ambassador in Ankara came from a colleague who had been there many years and left shortly after I arrived. He said, “Turkey is one of those countries where the more you know, the less you understand.” I hope that today’s discussions will give me, and maybe others, more knowledge and understanding.

The reasons for this hearing are self-evident. Questions are being asked about whether Turkey has changed its axis and reoriented its priorities, about whether it remains a friend and ally of the United States or is becoming, as Steven Cook of the Council on Foreign Relations recently suggested, a competitor or possibly a “frenemy.” That this debate is happening ought to be disconcerting to Turks who argue – as many in the military, foreign ministry and government did to me – that the United States is Turkey’s most important and only strategic partner. It frustrates the Obama Administration, which has invested heavily in U.S.-Turkish relations, including when the President visited Ankara in April 2009, when Prime Minister Erdogan came to Washington last December, and at the nuclear security summit here several months ago.

Of course, there have always been ups and downs in U.S.-Turkish relations. Those who think they remember the halcyon days of yore should read their history. Looking at reports in the U.S. embassy’s files put my problems into perspective while I was working there. Or consider a Turk’s point of view. He or she might have thought the word frenemy (if it really is a word) applied to the United States when in 2003-2007 we barred cross-border pursuits of terrorists fleeing back into northern Iraq after attacking police stations and school buses, or when the United States imposed an arms embargo after Turkish forces intervened in Cyprus in 1974, or when we accepted the brutal overthrow of Turkey’s civilian government in 1980.

But to stick with our own perceptions and priorities, a lot of mainstream observers think that it is different this time. Whether fair or not, or correct or not – and I think this is not an accurate image, Turkey’s picture in many circles here is monochromatic in unflattering ways: friend to Ahmadinejad and supporter of Iran, friend to HAMAS, shrill critic of Israel, and defender of Sudan’s Bashir. The flotilla incident and Turkey’s no vote on UN sanctions against Iran sharpened the issue. Several weeks ago, a senior U.S. military officer and great friend of Turkey confided to me with exasperation, “What in the world are we going to do with Turkey?” Uncertainty about Turkey and how to proceed with it is widespread. And that is at least as much a problem for Turkey – for Turks who value its five decade-old alliance with the United States, to which I believe Turkey is committed – as it is for anyone here.

One thing we have to do about our exasperation is fill out the picture. How Turkey does see things, and what are its leaders responding to and trying to accomplish? Picture Turkey on a map and go around it.

Iran

Turkey borders on Iran. For Ankara, it is a problematic country, a rival for hundreds of years. Most Turks I talked to believe the recent rise of Tehran’s influence has been fueled in part by the U.S. invasion of Iraq and its consequences and by the unresolved Israel-Palestinian conflict. They regard Iranian actions as inconsistent with Turkey’s interest in a stable, peaceful region, and I think their local geopolitical contest for influence is one we underestimate. But Turks also have to live next to Iran and do not want its enmity. So Ankara’s approach has been non-confrontational and continues to be so. It has worked indirectly to advance Turkey’s interests, including by developing non-Iranian Caspian energy export routes, deploying troops to the UN Interim Force in Lebanon, supporting such moderates as Lebanese Prime Minister Hariri and Iraqi leader Ayad Allawi, and engaging Syrian President Asad, whom it apparently hopes to moderate by lessening his dependence upon – or prying him away from – Iran.

Turkey does not want a nuclear-armed Iran. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and others worked in 2006-2007 to get Turkish buy-in for the approach taken by the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany – the P5+1. They were successful. I believe that Turkish leaders took a tough line on Tehran’s need to reassure the world by complying with its Non-Proliferation Treaty and International Atomic Energy Agency obligations. But the legacy of the Iraq weapons of mass destruction intelligence failures was that most Turks, including in the military and throughout the political elite, doubt the accuracy of Western intelligence on Iran’s nuclear efforts and fear the implications of war more than they fear the possibility of an Iranian bomb. Hence the Turks insistence on negotiations – an insistence on which the Turks are not alone, including among our allies.

Administration officials can speak more authoritatively than I can about how we came to cross-purposes on the Iran nuclear issue this spring. Suffice it for me to say that at the outset Ankara believed, with good reason, that the Obama Administration shared its objectives on the uranium swap proposal and backed its efforts. There were problems of timing, delivery and coordination, but this was not a rogue Turkey heading off in a new foreign policy direction with which the United States disagreed.

Obviously, Turkey’s no vote in the UN Security Council was unhelpful. In figuring out how we proceed on Iran with Turkey now, my overriding priority would be to comport ourselves in such a way as to ensure Ankara is with us in the next acts of the drama. I think the political, defense and security implications of what Iran is doing are very serious. Whatever the future brings, the situation requires us to have the fullest possible support of all our NATO allies, and geography puts Turkey at the top of that of that list. We can accomplish this through the fullest possible information sharing on what we know (and don’t know) and involving Ankara in the diplomacy – not as mediator probably, but also not as a bystander. It is a partner; we expect it to act like one, and we should treat it as one.

Iraq

Turkey borders on Iraq, where we have poured so much treasure and youth. Over 90 percent of the Turkish public opposed the U.S. invasion in 2003, and a greater percentage opposes our presence there now. Despite this, Turkish authorities want us to stay. They fear, and I think the public at some level shares this fear, that we will walk away too early and then Turkey will face a chronic crisis. Or, worse, that Iraq might be taken over by some dangerous new tyrant, fall under the control of another neighboring power, break up, or become a home to anti-Turkish terrorists. The PKK problem along the northern Iraq border is especially serious, but at least 2-3 years ago, so were anti-Turkish al-Qaeda elements in Iraq. Since 2005 and especially after March 2008, Turkey has been a constructive player on Iraq. We asked it to help draw Sunni rejectionists out of violence and into politics, and it did. At our request, Turkey helped facilitate the U.S. engagement with Iraq’s neighbors that the Baker-Hamilton Commission recommended. We asked it to deal with Kurdistan Regional Government leader Masoud Barzani. It has done so, getting help on the PKK problem and making itself a more effective player in supporting the Iraqi political process, which will be important as our own role declines.

Turkey’s role in Iraq is important and positive. To be frank, it got to be that way because American and Turkish leaders decided to overlook the March 1, 2003 disagreement at the start of the war and found common ground in helping Iraq stand back up. While it did not seem so simple at the time, in effect we dusted ourselves off and moved on. That is not a bad model for policymakers now.

Middle East

Turkey borders on Syria and the Middle East. Even before I left for Turkey, I heard people wonder what it was doing mucking about in Middle Eastern affairs. In the U.S. government, the people dealing with the Middle East are generally not responsible for Turkey, which is handled out of offices dealing with European affairs. But Ankara is far closer to Jerusalem than Riyadh is. (For comparison, Ankara is only a little farther from Jerusalem than Washington is from Atlanta.) There is Ottoman baggage with Arab populations that modern-day Turks do not talk much about, but Turkey is a Middle Eastern country. It is not surprising that Prime Minister Erdogan is popular there – of course, his populist rhetoric adds to that, as he intends. In any case, we should forgive Turks for thinking that they have a role there or that they are entitled to their own perspective. This seems especially the case when on the most important issues – Israel’s right to exist, the goal of two democratic states, Israeli and Palestinian, living side by side in peace and security, and the need for a negotiated (not imposed) solution – Turkey’s perspective is the same as ours.

Within Turkey, in Israel and in the West, Prime Minister Erdogan has been criticized for his shrill rhetoric toward Israel, especially on Gaza. Turks do not, of course, universally support his government, but they do almost universally share his underlying view that Israeli-Palestinian stalemate has persisted too long, that what is happening to Palestinians is unfair, and that they need help. I was in Turkey shortly after the “flotilla incident.” I heard many views about whether the government’s backing of the Mavi Marmara was wise, properly done or in Turkey’s interest; no one I talked to, and as far as I could tell none of the people they talked with, thought that it was wrong.

I don’t know what the way forward on Middle East peace issues is. Clearly, Turkey’s estrangement from Israel limits any role it can play for the foreseeable future. At no time soon will Ankara again be able to mediate between Syria and Israel –an effort that showed its value in keeping channels open after Israel’s September 2007 destruction of the Deir ez-Zor nuclear site in Syria. It is constructive that Senator Mitchell has included Turkey among the regional powers that he consults with from time to time, and I hope that continues.

Caucasus

Turkey borders on the Caucasus – Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. I know that you, Mr. Chairman, other members of this committee and many Americans have strong views about the Turkey-Armenia piece and about history that has not been entirely accommodated. The South Caucasus is a volatile and fragile part of the world, as Georgia 2008 reminded us. That conflict gave impetus to reconciliation between Turkey and Armenia. When President Sarksian and President Gul stood together in Yerevan a month after the Russian invasion of Georgia, the two leaders seemed symbolically to say, ‘we have a vision of the Caucasus, it’s not what just happened in Georgia, and we’re determined to take on the most difficult issues between us to try to achieve it.’ Unfortunately, Armenian and Turkish leaders concluded that they could not go forward now to ratify the protocols that called for normalizing relations and opening the border. I think doing so can still build the confidence needed for resolving the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan and for Turks and Armenians to deal with their past, present and future together in a forthright manner. I hope that Congress can support that effort.

In the interest of brevity, I have omitted mention of Cyprus, Greece, the Balkans and the Black Sea, and such other active items in U.S.-Turkish relations as energy, terrorism, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Suffice it to say that, in my view, on each of these we want fundamentally the same things, there are of course differences of view, and the United States and Turkey cooperate pretty well.

Change in Turkey

I noted earlier the rhetorical question of what other American ally borders on so many problems of such high priority to U.S. foreign policy. Looked at another way, is there another ally that has such a large stake in how so many problems that are so important to us get addressed?

A Turkey that is stronger than at any time in a couple hundred years is now inclined to try to influence events on its periphery in ways that it was not in the past. It does so partly because it can, but also because it is good politics. This reflects important and positive changes in Turkey. When it comes to foreign policy, public opinion matters in a way it did not even just a few years ago. Decades of pro-market policies have made Turkey’s the 16th largest economy in the world. Migration from rural areas to the cities and an expanding middle class are two other trends with huge political implications. In this more prosperous and confident Turkey, voters do not want their country to be a subject of others’ diplomacy or a bystander on regional issues. They want to see their country acting. They expect their government to do so. They expect it to act wisely, and I think one of our jobs is to help it do so.

My answer to my military friend’s exasperated question, “what in the world are we going to do with Turkey,” is that we have no choice but to work with it and work with it and work with it. It is hard, it is frustrating, and maybe it is messy. It is harder now with a democratic ally in which power resides in several places – and that is in general a good thing. It is the only way to go forward and the only way not to go back into recrimination and anger that ultimately could put American interests in the region at risk. It requires steady senior-level engagement, visits to Turkey by members of Congress such as you, Mr. Chairman, and not letting differences that are mostly tactical overwhelm our strategic interests. I thought it was highly important that President Obama met with Prime Minister Erdogan on the margins of the recent G-20 Summit in Toronto a month ago. According to the account I heard, the meeting was long, and the President was very direct, tough and critical. That is what it will take.

Thank you.