Chinese authorities blame foreign activists for inciting violent protests this week in Xinjiang, and say the Internet enabled them to do it. Uighur groups have used the Internet to rapidly get out images from what they say was a provocative government crackdown on a peaceful demonstration.

Following Sunday’s violence in Xinjiang region, Chinese authorities were hasty to point fingers.

Following Sunday’s violence in Xinjiang region, Chinese authorities were hasty to point fingers.

At a news conference Monday, Xinjiang’s police chief Liu Yaohua blamed the World Uighur Congress, an international Uighur rights group.

Liu accused the organization of distorting China’s ethnic and religious policy to stir up conflict. But he especially singled out the Internet, describing it as the main medium that foreign forces use to communicate with Uighurs in China.

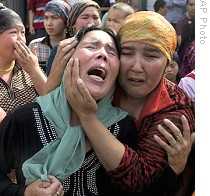

Uighur activists say a peaceful demonstration Sunday in Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi, turned violent after police began cracking down. Chinese authorities accuse groups like the World Uighur Congress of masterminding a riot from afar, in an effort ultimately aimed at creating an independent Xinjiang.

Twitter disabled

The government has acted quickly to block access to information. Authorities acknowledge that Internet service in Urumqi has been interrupted, but they do not say how long it will be out. They say the interruption was done legally, and is necessary to maintain social stability.

In Beijing, the Twitter messaging system, which protesters in Iran recently used to report on police crackdowns there, has been disabled. And while cell phone connections in the Xinjiang capital, Urumqi, still operate, getting a call to the city, or making an international call from there, is proving difficult.

Xiao Qiang teaches journalism at the University of California at Berkeley. He also edits China Digital Times, a round-up of Chinese-language content on the Internet.

Internet is playing a bigger role this year,” Xiao noted. “Partially because what happened in Urumqi was immediately exposed by lots of cell-phone cameras, digital cameras, videos – there’s a lot of witness(es), people [who] immediately wrote and sent out video images on the Internet.”

Internet gains importance

Xiao compares what happened in Urumqi to the events last year in the capital of Tibet, Lhasa, when scores of Tibetans clashed with security forces there. He says Internet use in Urumqi is much more than in Lhasa.

He says Chinese authorities immediately began removing all Internet references to the Urumqi protest, and blocking social networking sites.

There are ways of getting around Web restrictions. Xiao says Chinese Internet users have been engaging in a tactic called “tomb digging.” Users on a bulletin board forum post an up-to-date response to an older post that mentions Xinjiang and has not yet been deleted.

“It’s basically a covered-up way to discuss those banned issues, under the nose of the editors of those forums, and it could be very effective,” Xiao said.

What caused violence?

Xiao says the opinions on Internet forums are much more varied than those in official Chinese media. Some support the government and the use of force to crack down on chaos. But other users are mistrustful of the government’s handling of the situation and are more reflective about the cause of the violence.

The Uighurs are a mostly Muslim ethnic group with cultural and linguistic ties to Central Asia. For years, many have complained that country’s ethnic majority, the Han, are taking over their traditional home, Xinjiang, in western China, and that they face government discrimination.

University of Washington Chinese studies Professor David Bachman says the images of the crackdown he has seen show the use of force has been “extensive” and “in some ways merciless.” Despite the government’s criticism of the Internet, the wide dissemination of pictures like those also helps spread Beijing’s stern warning.

“Clearly, the Chinese government is saying to Uighurs and to others in Xinjiang and to Tibetans and other minority groups, or for domestic protesters in the heart of China, that protests will be met with strict and harsh measures. Don’t even think about it,” Bachman said.

Possible solution

Bachman says cracking down – on both a restive minority and on public access to information – may solve short-term problems, but will only breed more resentment and opposition in the long run.

He says there is no quick fix to the long-standing tensions between Han Chinese and Uighurs. He says any efforts to make the problem better, though, should first focus on deeper issues, such as trying to alleviate perceived imbalances, discrimination and inequality.

Voa News