26 October 2011, Wednesday / HATİCE AHSEN UTKU, İSTANBUL

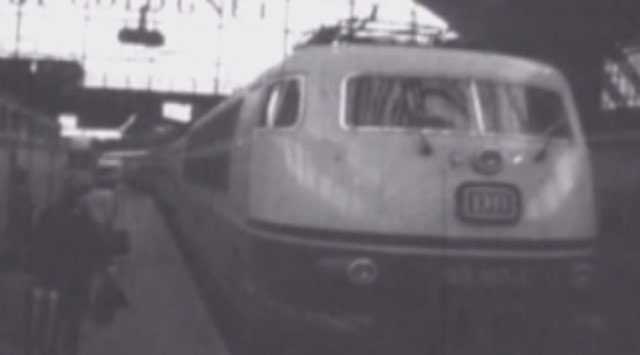

It was 50 years ago when thousands of Turkish workers, all filled with hope and expectations, waved at their families and loved ones from trains headed for Germany.

It was the year 1961 when the bittersweet story that was to connect Turkey and Germany started. It was when the word “immigration” would gain new meanings and dimensions for Turks. It was when Turkey and Germany signed the Gastarbeiter protocol — the Worker Recruitment Agreement. During the 50 years that have passed since, many things have irreversibly changed.

The 50th anniversary of such a seminal event is now being commemorated via a host of art events by the Goethe-Institut İstanbul, from stage plays to films, and from conferences to concerts, workshops and exhibitions from Oct. 20 through Dec. 10.

One of the main events of the project, an exhibition titled “Fiktion Okzident” (Fiction Occident), features the works of 18 artists at the Tophane-i Amire Cultural Center. Another event on the lineup, a film program titled “Karşıdan Bakış — Göç ve Sinema” (A Look from Across: Migration and Cinema), provides a selection of films exploring the perspective of “the other.” Other events include concerts and workshops by Turkish-German hip hop artist Sultan Tunç at Babylon; the project “Gidenlerin Öyküsü” (The Story of Those who Left), which will be detailed in an upcoming documentary that follows a train headed for Munich from İstanbul’s Sirkeci Railway Station on Oct. 26; and the conferences “Ulusaşırı Göç” (Supranational Migration) and “Göç ve Edebiyat” (Migration and Literature) at Bilgi University’s Dolapdere Campus. Finally, a musical titled “Yaşamayı Beklerken” (Waiting to Live), written by Anja Tuckermann and Haluk Yüce, will be staged at the Beyoğlu Kumbaracı50 as the closing event.

“In order to focus Turkish attention on the positive developments of the migrants in Germany and to bring the two cultures closer together, the Goethe-Institut is organizing a wide-ranging program with exhibitions, readings, lectures, concerts, workshops, theatrical performances and a film series,” explains Claudia Hahn-Raabe, the director of the Goethe-Institut İstanbul in an interview with Today’s Zaman.

“… German-Turkish cultural history is characterized by mutual projections, romantic fantasies and prejudices. These imaginary worlds exist on both sides. They are part of the mental foundations of the social, cultural and political German-Turkish reality. When on Oct. 10, 1961, a recruitment contract with Turkey was signed and millions of workers from Turkey were recruited, these notions were put on an entirely new and much broader social and cultural footing. A large percentage of the 2.4 million people of Turkish origin now were born in Germany. They know Turkey only from travels and from what they were told. While many are successfully integrated, there are still strong feelings of alienation on both sides, in large part caused by cultural differences and ignorance. These feelings result in rejection by some groups of the native population and partial withdrawal into the oft quoted ‘ethnic niches’ by some of the Turks. So this program will reflect the cultural, political and social effects of a shared history,” she explained.

For Hahn-Raabe, there are many lessons to be learned — for both the Turkish and the German sides — from this long-term experience. “The cultures of both countries need to be aware that an appropriate manner of dealing with the history of migration is overdue,” she notes. “Germany needs to come to terms with the fact that it is an immigrant country. It must expand its integrative efforts and take care to avoid negatively biased press coverage. Above all, it needs to oppose the negative connotation of the terms ‘Turkish immigrants’ and ‘Germans of Turkish origin.’ The same is true of the Turkish side,” she notes. “‘Against each other’ needs to become ‘with each other,’ but this can only happen when both sides know and respect one another. Exchange between the two countries therefore needs to intensify, especially in the cultural sector.”

In this context, the Goethe-Institut felt committed to undertake a project that would cover the issue in the broadest way possible. “We have decided on a wide-ranging program with an exhibition, readings, lectures, concerts, workshops, a theater performance and a film series in order to present our mutual history in as many facets as possible,” says Hahn-Raabe. “And as a matter of principle, all of the events are organized together with Turkish partners,” she adds.

Shift in time, shift in perspective

This is definitely not the first time that Turkish workers’ migration to Germany has been the subject of art and literature; on the contrary, there has been quite a large number of works on the issue. However, was there no shift in perspective since 50 years ago? According to Hahn-Raabe, is answer is affirmative. “At the beginning of the ’70s, the problems of the guest workers were primarily dealt with. The term ‘guest workers’ in itself is telling,” she explains, and continues: “In the ’80s, the so-called second generation became the focus. These people were either already born in Germany or had moved there at an early age. They differed from the first generation in the importance they gave to questions of identity and their existence between two cultures. The term ‘guest worker’ was now changed to ‘migrant’.”

For Hahn-Raabe, the following decade and the following generations were destined to be more promising in terms of coexistence. “Since the ’90s, the differentiation between the generations has faded,” she says. “Now, artists of Turkish background are individually noticed, known by name and accepted as part of the German cultural landscape.”

This evolution has its reflections on productions as well. While films and stories about the adaptation and identity problems of the Turkish immigrants were very popular in the earlier decades, the focus of the artwork has shifted to a different point of view as well. “By now the image of the erstwhile guest worker has changed considerably,” indicates Hahn-Raabe. “The artists and their works are increasingly perceived as detached from possible historical or problematic connotations. Eminent examples are the film director Fatih Akın, the writer Zafer Şenocak and the music group Microphone Mafia.”

Given this shift in time and perspective, the project is expected to reflect this variety. “We would like to show as diverse a picture of our common history as possible and underscore the changes that have happened,” notes Hahn-Raabe. “Therefore, we have invited artists of the first, second and third generations, and have organized cooperation opportunities between German artists, artists of Turkish descent living in Germany and Turkish artists. For the central exhibition project “Fiction Occident” 18 contemporary artists whose work deals with these imaginary worlds and their clash with reality were invited. Among them are artists who were born in Turkey and today work in Germany, artists who were born in Germany and commute between the two countries and artists in Turkey who reflect the consequences of internationalization.”

Happily, the project is not confined to İstanbul, as it also incorporates Germany. “Parts of the program series will also be seen in Germany,” explains Hahn-Raabe, adding: “For instance, the exhibition ‘Fiction Occident’ will go to Berlin in the spring of 2012, and the concert with Microphone Mafia and Ayben may go to Munich in cooperation with TRT Türk. All German migrants in Turkey are invited to the events and politicians such as Cem Özdemir, Dr. Anna Prinz from the German Foreign Office and North Rhine-Westphalia Minister of Labor Guntram Schneider will participate. Moreover, many events will be organized by German cities.”

Ahmet Davutoglu met Christian Turkish citizens at the Saint Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church and St Petrus and Paulus Church in Cologne.

Ahmet Davutoglu met Christian Turkish citizens at the Saint Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church and St Petrus and Paulus Church in Cologne.