A Blog on Russia, Central Asia and the Caucasus

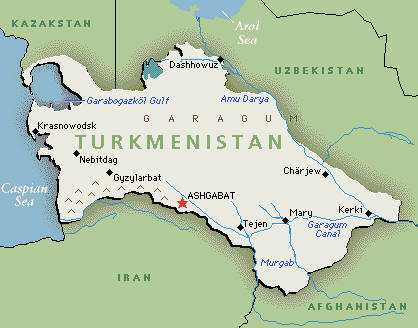

On Thursday, a ceremony in the State Department will mark the retirement of Steven Mann, Coordinator for Eurasian Energy Diplomacy, after 32 years with the U.S. diplomatic service. The 58-year-old Mann served most of the last 17 years in senior positions in the Caucasus and Central Asia: He opened the U.S. Embassy in Yerevan in 1992, was ambassador to Turkmenistan, and tried to negotiate a deal between Armenia and Azerbaijan on Nagorno-Karabakh. For the last several years, Mann was America’s man on the spot in the New Great Game on the Caspian Sea.

I visited Mann at his Chevy Chase home. Amid stacked up magazines and books, Mann told me that Europe’s “energy security” is not necessarily at peril. And, for O&G readers, he broke one bit of historical news: Remember the demise of the trans-Caspian pipeline in the chapter An Army for Oil? The one in which then-Turkmen President Saparmurat Niyazov persisted in demanding a $500 million bribe of the Bechtel-General Electric consortium? It turns out that Niyazov originally requested $5 billion. The edited interview:

Q – Does the U.S. need a high-level ambassador on Eurasian energy? And what is your advice going forward?

A – Yes it is helpful. But we also have to get away from Nabucco hucksterism.

Q – What is that?

A – In terms of the wrong lessons learned from [the Baku-Ceyhan pipeline], the wrong lesson learned is to adopt a project and attempt to bring it about through political will. I think so much of the governmental activism on both sides of the Atlantic the last few years has been devoid of a commercial context. There have been quite a number of officials who know very little about energy who have been charging into the pipeline debate. Nabucco is a highly desirable project, don’t get me wrong. But there are other highly desirable projects besides Nabucco. And the overriding question for all these projects is, Where’s the gas?

Q – South Stream was Putin’s response to Nabucco. Did the U.S. blunder by promoting Nabucco before having the commercial context?

A – In terms of whether we are talking EU or US diplomacy, I think you have to be credible. All too often we’ve gotten out ahead of the commercial realities of Nabucco. You have to be able to point to an upstream supply. You have to have a commercial champion. And governments don’t build successful pipelines. Consortia do. The object of any envoy should be to get all those stars aligned before you give the full embrace to any project.

I think Secretary Clinton will bring a more unified focus to the U.S. effort. In the previous administration, we had six special envoys on energy in the State Department, and three deputy national security advisers on the [National Security Council] staff.

Q – Is that too many?

A – It’s four too many in State. And three too many at NSC.

Q – The stated reason for Nabucco is to diversify Europe’s energy supply. Is that a valid enough reason for U.S. involvement? And is European energy security a genuine issue?

A – Anyone who makes that argument knows very little about energy. And I often heard those arguments in the White House Situation Room. Diversification is an objective good. But it can be achieved in ways other than pipelines. The best thing Europe could do for its security is to link its energy grid, which it’s already doing.

Q – Is there alarmism on the subject?

A – The January cutoff of gas through Ukraine only affected 2-3% of European consumers.

Q – So it is overplayed.

A – Yea, I think it was overplayed. What also was underplayed was how successful the Europeans were in shifting gas, linking grids. That’s the untold story of [the January cutoff].

Q – The corollary – that Russian domination of supply equals a political threat in Europe – is that also alarmist?

A – With the EU, I think it’s hard to make that case. That’s the kind of argument that has to be dissected on a country-by-country basis. But Gazprom has been an extremely reliable supplier for 25 years. And I think Gazprom will continue to be an extremely reliable supplier to Europe.

Q – So really one should not be vexed if and when Nord Stream and South Stream are built? And if it takes some time for the ducks to be lined in a row for Nabucco, so be it?

A – Basically, yes. I think Nabucco is far more important to Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan than it is to the EU.

Q – In the late 1990s, there was the initial effort by Bechtel and GE Capital to build a trans-Caspian pipeline from Turkmenistan to Baku.

A – What happened was that Niyazov, with his Soviet mentality, demanded so-called preliminary financing. That is, an upfront payment to do the project. [The consortium] already paid a signing bonus of $10 million. But then Niyazov demanded in the range of $5 billion. Then it came down to $3 billion. And the consortium said, ‘This is utterly unrealistic.’ Niyazov thought they were bargaining. So he dropped the demand to $1 billion; then it came down to $500 million. The consortium said, You have until March 2000 or we walk. And at that time, they walked.

The fundamental problem, and it’s relevant today, is that a foreign investor cannot rely on a governmental entity [in Turkmenistan] to supply the upstream, to supply the product.

Q – Was it ever realistic that Niyazov was going to hook up with the East-West Corridor?

A – It was and it is realistic. Without alternatives to the Gazprom monopoly, Turkmenistan has to accept the price that Gazprom is willing to pay. There is a powerful commercial logic to a trans-Caspian pipeline.

Q – What is the best way today for a Caspian republic to get along in the region?

A – Kazakhstan is a good model of how to develop a Eurasian energy sector. You’re good partners with Russia, but you take advantage of foreign technology and capital.

Q – Does Russia have a role in helping to create a thaw between the U.S. and Iran?

A – Every time there is a substantial political change in the U.S., the oil and gas industry gets up on its tip-toes and says, ‘Aren’t we about to have a change in policy?’ You saw this with the Bush-Cheney election in 2000; the industry thought now was the time it would happen. You saw it after the [2001] invasion of Afghanistan, with certain cooperation and contact between the U.S. and Iran. You’re seeing it now with the advent of the Obama administration. So this is something that the oil and gas industry is always waiting for – that change.

Q – You are saying that this is nothing new.

A – It is nothing new.

Labels: Azerbaijan, Caspian, Kazakhstan, Nabucco, nord stream, oil, south stream

http://oilandglory.com/

ANTALYA (A.A) – 03.07.2009 – The Turkmen tourism minister expressed his country’s willingness to make use of Turkey’s tourism experiences.Gurbanmammet Ilyasov, the head of the Turkmen State Committee for Sports and Tourism, visited the Turkish Mediterranean city of Antalya, and said Turkmenistan wanted to benefit from Turkey’s tourism experiences.

ANTALYA (A.A) – 03.07.2009 – The Turkmen tourism minister expressed his country’s willingness to make use of Turkey’s tourism experiences.Gurbanmammet Ilyasov, the head of the Turkmen State Committee for Sports and Tourism, visited the Turkish Mediterranean city of Antalya, and said Turkmenistan wanted to benefit from Turkey’s tourism experiences.