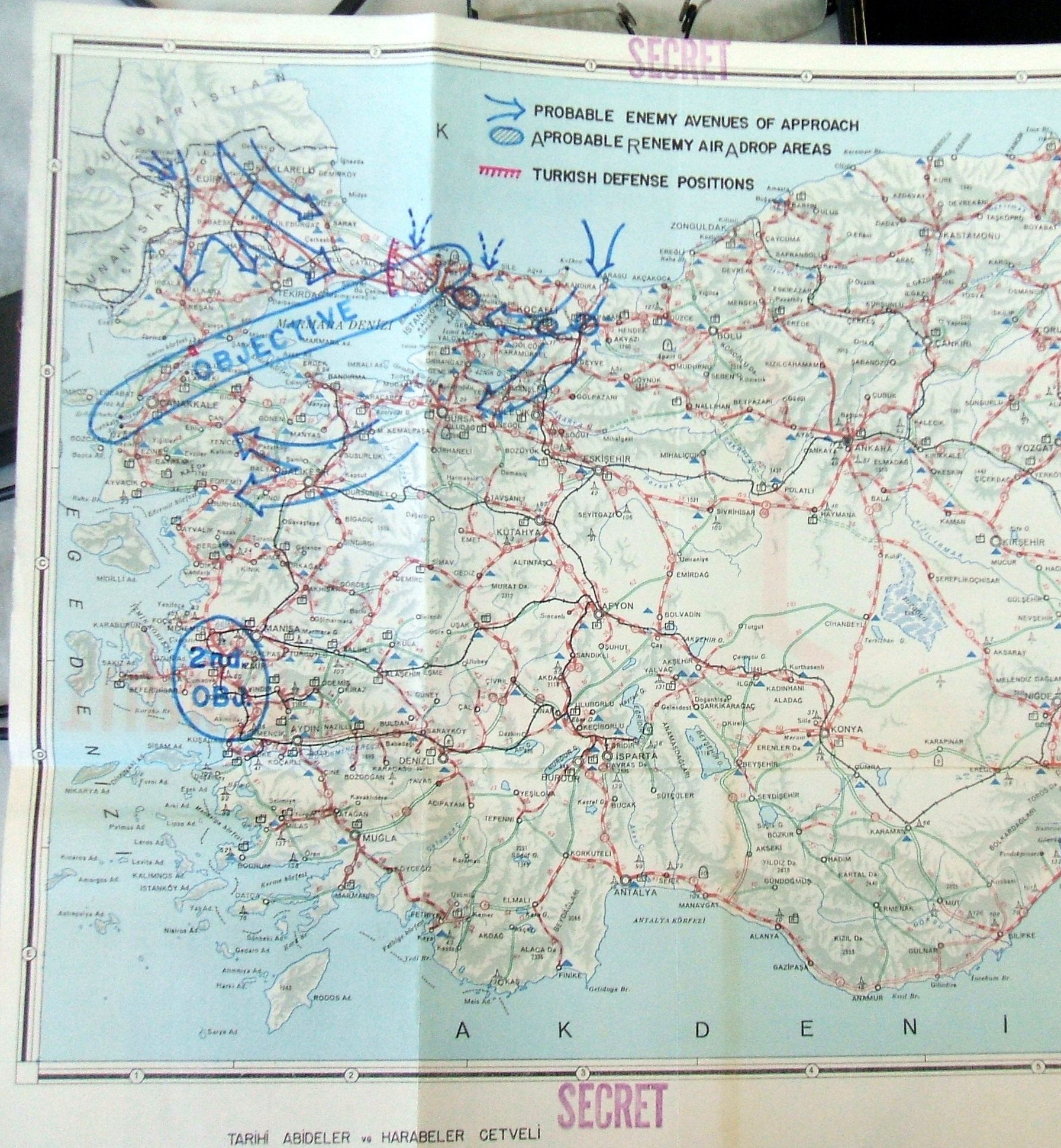

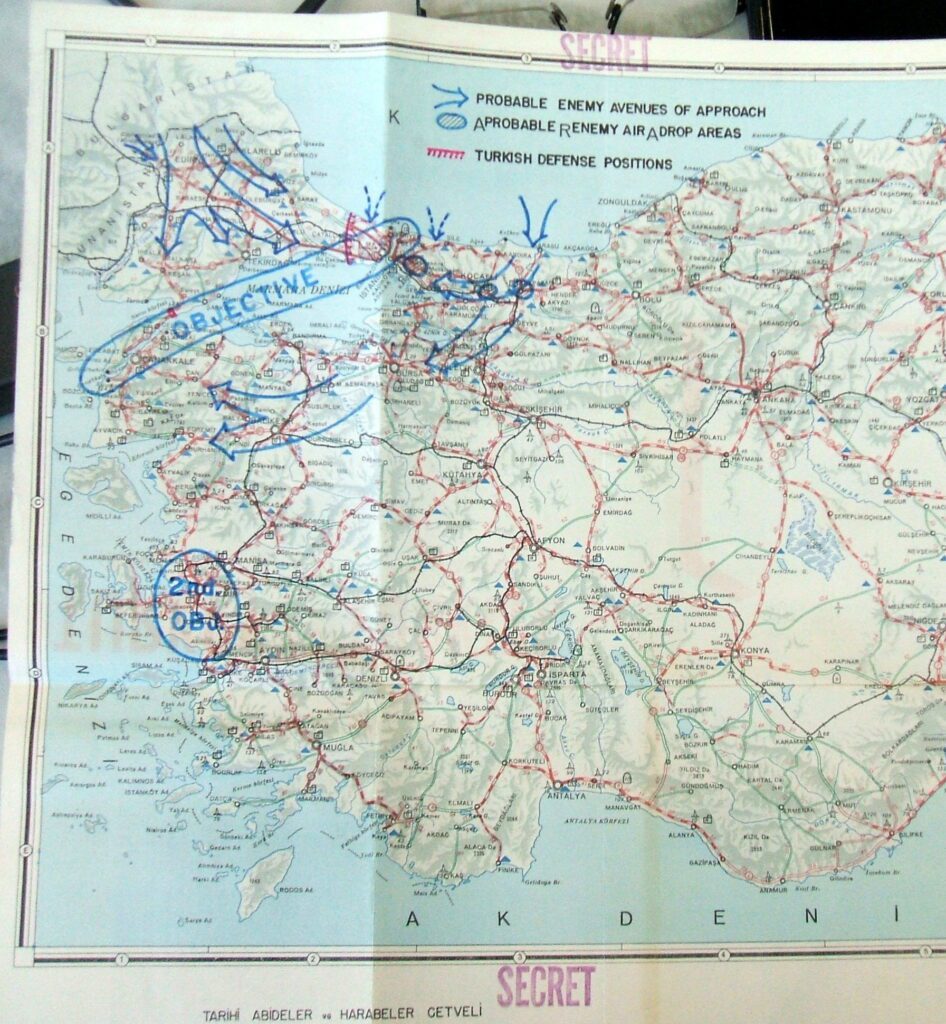

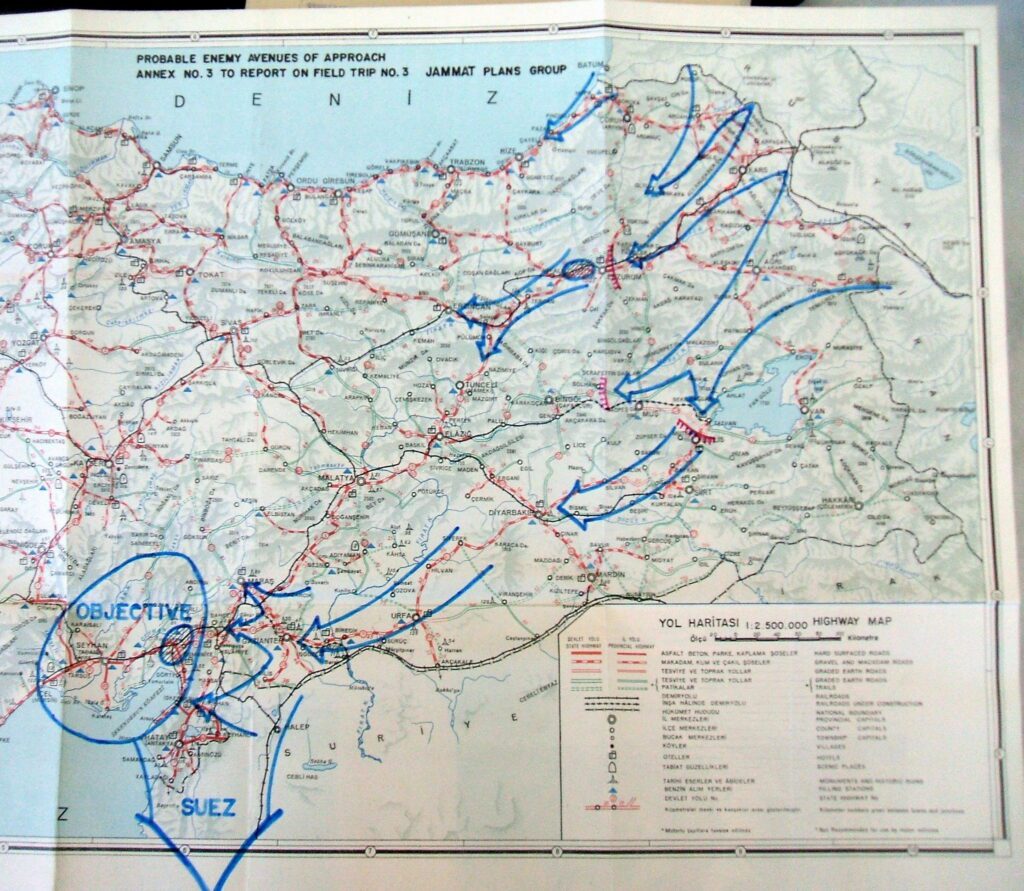

Probable Enemy Avenues of Approach

30 years later, of course, Turkish-Russian relations were even worse. These maps, from the Joint American Military Mission for Aid to Turkey reflect early cold war American expectations about how the communists would attack Turkey. Though a good deal of strange conspiracy theories have arisen from the mistaken assumption that whatever the military makes plans for reflects its official policy, these maps at the very least are a reminder that at the time, an invasion like this and the world war it would trigger were considered real possibilities.

A direct attack on the straights accompanied by an invasion from Bulgaria

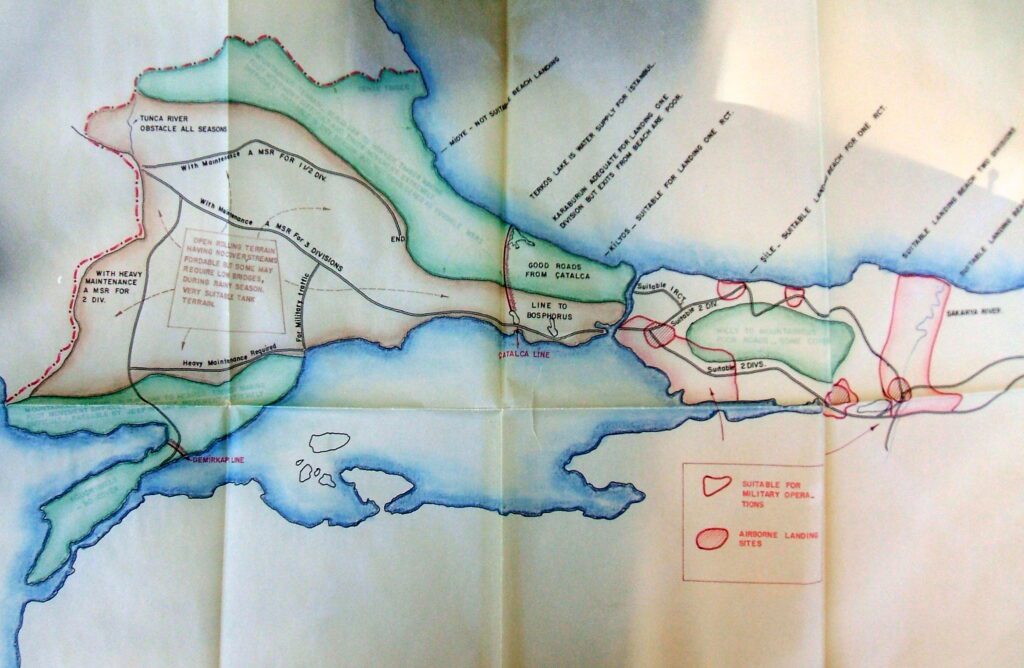

The Turkish defense of Istanbul at this time was centered around the Catalca line, running across Thrace on the raised ground north of Buyukcekmece, the same point where the Ottoman army held off Bulgarian forces in 1913. A more controversial subject, between American military planners and their Turkish colleagues, was where America would mount its defense. One plan, understandably unpopular with Turkish leaders, involved writing off most of Anatolia and trying to stop the Russian advance into the Middle East at the Taurus mountains north of Adana.

Finally, though not suitable for an amphibious landing, Midye, now called Kiyikoy, is a delightful place for a weekend trip from Istanbul.

Source: midafternoonmap.com/2013/01/the-russians-are-coming-or-still-seeing.html