Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mehmet Seyfettin EROL, Gazi University, Deputy Head of International Relations Department

The “Millennium Development Goals” (MDG) project which is being implemented under the leadership of the United Nations (UN) focusing

to solve the eight fundamental issues facing the human beings at the global level, regarded as a courageous step for the future. The realization of the goals

will be a historical turning point in terms of the great philosopher Immanuel Kant’s “Perpetual Peace” which is still regarded to be a utopia today without any

doubt. In other words, the UN has undertaken a mission issued by the leaders in the Millennium Summit 11 years ago and targeting a more prosperous, just and

peaceful world.

Well, how much is it possible to implement this project which is almost challenging the next millennium in the name of improving the welfare and quality of life of

the humanity? Especially, how will this issue be solved when materialistic perception of globalism that is being made dominate the world and subsequent

problem of evaluating moral-subjective values are considered? Will the UN be able to get over this paradox in an atmosphere in which quantity forestalls

quality and, with regard to this, “imposing” proposed solutions are put on the market as “standard” packages under

different names and an atmosphere in which all these “standard” packages cause more problems?

No doubt neither at present nor in the medium-term it is easy to answer these questions. Especially approaching to the issue in this way and seeking for

“yes-no” answers to the said questions will mean dynamiting the way to the solution. Anyhow, such an approach will go against both the spirit of social

sciences and the methodological understanding. Our goal here is, through this kind of questions, to bring up the matters that should have been asked and

raised in the first place and to ensure the development of possible solutions, may be by saying “the Emperor is bare.” For this reason, there is no need to

enter into philosophical discussions and very complex methods. Even putting the reality of the world and the statements in the published declaration will be enough

to depict a certain number of challenges in front of the process. Accordingly, although the MDG are launched as a project to find a common solution to the

problems of the humanity at the global level, in practice they are open to be attributed different meanings as long as a common road map cannot be introduced.

Especially after the post-Cold War era within a context where some local issues which could be solved locally are globalized over the concepts are brought into intervention tools, so it is inevitable for some nation-states to consider this type of UN based projects cautiously. Therefore, it seems that it wouldn’t be so easy for our world experiencing ebbs and flows between the globalization and nation-state process to realize the targets set in the MDG in terms of the implementing developments and practices

about “human rights-democracy- governance” understandings on national, regional and global basis. In other words, this cautious approach will endure unless the

mentality does not change and an objective viewpoint considering the local in many respects and in this context balancing the local-global with collaboration

is not put forth instead of top-down approaches and interventions. On the other hand, as it is partially mentioned above, this is not a problem that

cannot be overcome. The key to overcome it lies in listening the local, trying to grasp its realities, and taking its journey, experience, values and

sensibility into consideration. Hence, it is time to recognize the local as a solution partner rather than taking it only as the source and field of

problems. After all, the locals are global in total and today goals stated with regard to the MDG are predicated on the solution of the problem that grows out

of the locals within the pioneering powers of the globalization. Additionally, it should be accepted that the problems formed with regard to the MDG are not

belong just to the century or millennium we live and that their roots originates in centuries before.

As of today, it cannot be a coincidence that almost the whole of the problems which are on the spotlight of the world agenda and tried to be solved in the

context of the MDG are seen in the former colonial countries, too. As a matter of fact, the said problems’ moving away from their limited and local image,

spreading, deepening, gaining a global character and, at the end, turning into threats to and elements of instability for the future of the whole humanity

have their roots in the centuries before.

In such an environment how can geographical discoveries, colonialism and, as an inevitable outcome of these, imperialism together with the globalization be

kept out of all these? What can be said for materialism that tramples all moral values-beliefs by making material forestall meaning and what can be said for

distorted understanding of modernization that turns people into consumption slaves? Today how many of the problems emerging in the context of the MDG has followed a development process independent from these mentioned points?

We know that projects are represented as they are very much humanistic in the global manner. However, since they are kept limited to certain regions for

certain reasons and are launched as peculiar to these regions, they can face some challenges in practice. As a result, in resolution of such kind of

problems it is necessary first to have a clear and well-intentioned position and second to take steps accordingly. Then, what can be done at this point?

There is no need to go so far to find an answer to this question. To find an answer, it will be enough to look at successful approaches and practices that this

region contains within and implements in line with its realities and values, that have their roots in centuries before, that maintain their existence today,

and that take human as its base. In this context, two leading practices of civil society perception and solidarity in Uzbekistan are noteworthy. Focusing

on these practices shows that indeed they are successful models for a significant part of the problems drawn out of the MDG.

As a result of the historical practices and experiments, the civil approach understanding in Uzbekistan is based on the protecting the people from many

difficulties and threats and aiming social justice, equality and healthy social structure in such an unstable region like Central Asia. It is known that these

human based practices have the capacity to solve many interdependent social-individual problems with on time interventions. This nongovernmental

approach which is taking the family as the base and the woman and the children in the family as the focus and imposing the necessity of all types of good education is a successful practice within the power of the local completely. These practices are called “Makhalla System” and “Kamalat Youth Movement” and as mentioned above briefly they have got human based nongovernmental understanding, a deep history and tradition in the country.

The governing idea of the “Makhalla System” that has been implemented after the independence of Uzbekistan as one of the most concrete examples of participationary and direct

democracy is making the system, in which the basis of social structure is formed, the ground which prepares the youth for the future. With another words, “Makhalla is a big family”, “Makhalla is the cradle of education” idea and together with “Economic development starts from the Makhalla” understanding constitutes the core of this model.

Constituting the first stage of the participatory administration, “Makhalla Foundations” started their activities in small Makhalla with 5000-7000 residents in which everyone knows each other. They have a spiritual, educational, informative and ability improving attitude. In this context, education, social assistance, environmental health and development; solution to social problems of the residents; help for the ill, aged and needy; employment and construction of social facilities for the youth; attachment of importance to women and their problems; and “Women Affairs Commission” working on a voluntary basis are outcomes of the “on-site and on time solution” perception of this model.

Moreower, “Kamalat Youth Movement”, formed in 2001, accepts young people aged between 14 and 28 as members and prepares them for the future with the necessary facilities. It is a civil society movement working actively on the issues such as unity of the youth, protection of their interests, improvement of their abilities, solutions to their problems, teaching them their social rights and guiding them in the way of entrepreneurship, and sport.

Therefore, as it is seen in this study primarily some problems emerged at the local-global basis from the aims put forth in the MDG and some concerns carried

by the local and ignored realities will be considered, firstly. Then, the importance and role of Uzbekistan will try to be emphasized in order to understand the

local very well and adaptation of successful practices of it into the global process. At this point, the contributions of “Uzbek Model” and its NGO understanding with “Mahalla System” and “Kamalat Youth Movement” which are based on their historical depths, strong tradition, experience and human based dimensions can be considered as a

successful example and experience in terms of challenging with the fundamental issues facing the human beings at the global level.

In the 40s, Turkiye experimented with elevating the education level in the countryside. `Village institutes’ (Köy enstitüleri) were founded according to the ideas of philosopher-educator John Dewey, who had visited Turkey in 1924. In his opinion classical education had to be combined with practical abilities and had to be applied to local needs. However, it was the central government which regulated this by law. Mid September lessons started for the pupils of the village institutes. They took theoretical and practical lessons which were supposed to be useful for daily life in the village. There was also resistance against this secular and mixed education. It was feared that it would educate ‘the communists of tomorrow’. In 1953 the village institutes were closed.

In the 40s, Turkiye experimented with elevating the education level in the countryside. `Village institutes’ (Köy enstitüleri) were founded according to the ideas of philosopher-educator John Dewey, who had visited Turkey in 1924. In his opinion classical education had to be combined with practical abilities and had to be applied to local needs. However, it was the central government which regulated this by law. Mid September lessons started for the pupils of the village institutes. They took theoretical and practical lessons which were supposed to be useful for daily life in the village. There was also resistance against this secular and mixed education. It was feared that it would educate ‘the communists of tomorrow’. In 1953 the village institutes were closed.

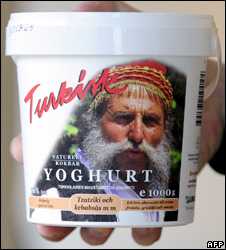

There is evidence of precultured milk products being produced as food for at least 4,500 years. The earliest yoghurts were probably spontaneously fermented by wild bacteria.The oldest writings mentioning yogurt are attributed to Pliny the Elder, who remarked that certain nomadic tribes knew how “to thicken the milk into a substance with an agreeable acidity”. The use of yoghurt by medieval Turks is recorded in the books Diwan Lughat al-Turk by Mahmud Kashgari and Kutadgu Bilig by Yusuf Has Hajib written in the 11th century. Both texts mention the word “yoghurt” in different sections and describe its use by nomadic Turks.

There is evidence of precultured milk products being produced as food for at least 4,500 years. The earliest yoghurts were probably spontaneously fermented by wild bacteria.The oldest writings mentioning yogurt are attributed to Pliny the Elder, who remarked that certain nomadic tribes knew how “to thicken the milk into a substance with an agreeable acidity”. The use of yoghurt by medieval Turks is recorded in the books Diwan Lughat al-Turk by Mahmud Kashgari and Kutadgu Bilig by Yusuf Has Hajib written in the 11th century. Both texts mention the word “yoghurt” in different sections and describe its use by nomadic Turks.