By JOE PARKINSON

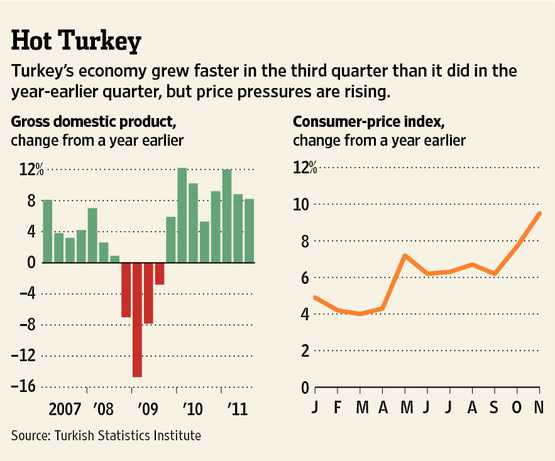

ISTANBUL—Turkey’s central bank governor warned Monday that inflation was his No.1 problem, as data confirmed the economy expanded 8.2% in the third quarter, smashing economists’ expectations and underscoring its reputation as Eurasia’s rising tiger.

Monday’s official growth figure, compared with the same period a year earlier, dramatically exceeded market forecasts of a 6.6% gain and followed an 8.8% expansion in the second quarter.

Monday’s official growth figure, compared with the same period a year earlier, dramatically exceeded market forecasts of a 6.6% gain and followed an 8.8% expansion in the second quarter.

Turkey’s rapid growth momentum comes at a time when many of Ankara’s neighbors in the Middle East and Europe are struggling with political turmoil and bailouts.

In August, Turkey’s central bank cut its main policy rate, citing concern over economic turmoil in the European Union. The bank has since moved to raise other interest rates as it battles rampant credit growth. Its concern over inflation—which rose sharply in recent months, driven by the Turkish Lira’s 30% fall against the dollar—stands in contrast to the stance of many emerging markets, which have begun cutting interest rates to spur growth amid concerns over the deteriorating global outlook.

Speaking to reporters in London following the publication of the economic growth figures, Governor Erdem Basci said that inflation, which rose at its fastest pace in 1½ years in November to hit an annual rate of 9.5%, was now the “No. 1 problem” for the Turkish economy and that Ankara was ready to tighten policy further “if necessary.”

At the same time, he said he was confident the bank’s decision in November to effectively double the overnight borrowing rate for commercial banks to 12.5% would be enough to combat the pressure.

The governor’s comments appeared designed to soothe investor nerves over the prospect of a pronounced rise in prices after Turkey’s stellar gross domestic product figures confirmed the economy’s 10th consecutive quarterly expansion and a 9.6% expansion in the first nine months of the year.

Market reaction to the data underscored those concerns, as the lira initially trimmed gains Monday before falling to trade almost 1% lower against the dollar. Turkish stocks extended losses after opening lower on mounting investor nerves over the global outlook.

The selloff also came despite positive data on Turkey’s hefty current-account deficit, considered by many investors to be the economy’s Achilles heel. The deficit narrowed to $4.2 billion in October, after a $6.8 billion expansion in September, according to the central bank. That figure also beat market expectations of a $5 billion expansion, and suggested a marked turnaround in the balance in the growth of imports and exports. Import growth in the third quarter versus the same period a year ago slowed to 7.3% from 19.2%, while exports expanded 10.8% in the third quarter after a 0.6% rise in the previous period.

Turkey’s Deputy Prime Minister and most senior economic policy maker Ali Babacan said the data suggested 2011 growth would expand more rapidly than the government’s expectation of 7.5% and that Turkey would be one of the “world’s fastest-growing economies in 2012,” Turkish television channel CNBC-e reported.

Although economists were united in their surprise at the pace of growth, which prompted upgrades to Turkey’s GDP forecasts at several brokerages, many appeared to disagree on whether the data underscored Turkey’s momentum or spotlighted the imbalances in the economy.

“The Turkish economy is unstoppable … importantly, seasonally adjusted sequential quarterly growth in the third quarter was 1.7%, which was a surprise to us and probably to market players, since we have expected a very mild increase,” said Ozgur Altug, chief economist at Istanbul-based BGC Partners.

Royal Bank of Scotland said the data showed that Turkey continues to show “Asian-style growth dynamics,” but stressed there was little evidence of a marked improvement in the current-account deficit, which is expected to hit around 10% of GDP this year.

Turkey’s red-hot growth stands in contrast with most neighbors in the European Union, in particular Greece, whose former Prime Minister George Papandreou called on his citizens to emulate the success of his country’s old rival in bouncing back from economic adversity. Rapid growth swept Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan to re-election June 12, cementing his position at the head of the region’s emerging political and economic power.

A breakdown of the third-quarter GDP figures showed broad-based rises in output, with construction expanding 10.6%, manufacturing 8.9% and financial institutions a whopping 15.8%. Private consumption, which has propelled much of Turkey’s stellar rebound from recession as consumers have binged on cheap credit, also continued to expand strongly, posting 7% growth.

But some economists cautioned that the lagging third-quarter figures didn’t contain the impact of the central bank’s moves to tighten policy by widening the interest-rate corridor and restricting liquidity. Capital Economics said in a research note that “while today’s data were stronger than anticipated, we think the following quarters’ data are likely to get worse … The data do not yet reflect the impact of tighter monetary policy since late October. This has pushed up interbank rates and is likely to weaken domestic demand even further by restricting access to credit.”

Write to Joe Parkinson at [email protected]

via Turkish Economy Booms – WSJ.com.