By Neville Teller — (March 19, 2013)

It was in April 1987that Turkey knocked on the EU’s door and asked to be let in. Twenty-five years later, Turkey is still lingering on the threshold.

One key factor barring the way to Turkey’s full membership occurred many years before it applied.

The population of Cyprus has historically consisted of about 75 per cent Greek and 25 per cent Turkish origin. Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Greek Cypriots began to press for Enosis − union with Greece. Matters came to a head in 1974 when the military junta then controlling Greece staged a coup in Cyprus and deposed the president. Five days later, Turkey invaded and seized the northern portion of the island. The Turkish invasion ended in the partition of Cyprus along a UN-monitored Green Line. In 1983 the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus declared independence. Turkey is the only country in the world which recognises it.

Greece itself was admitted to the EU as far back as 1981; Cyprus (the portion, that is, not occupied by Turkey) became a full member in 2004. So one major stumbling block to Turkey’s accession is the fact that the country is at daggers drawn with two established EU members.

But that is only one stumbling block among several. Also to be considered is the direction that Turkey has been taking on the international scene since its current government came to power.

From the time Recep Tayyip Erdogan became prime minister in 2003, Turkey’s old secularist, pro-Western stance began to change, and support for Iran and the Islamist terrorist organisations Hamas and Hezbollah began to dominate Turkey’s approach to foreign affairs.

Erdogan, a charismatic politician, acquired his pro-Islamist sympathies while still at university. In 1998, when mayor of Istanbul, they earned him a conviction for inciting religious hatred, and he went to jail for several months. All the same, in 2002 his Islamist AKP party won a landslide victory in the elections, and Erdogan became prime minister.

Rooted as he is in hard-line Islamism, Erdogan’s unqualified condemnation of Israel’s incursion into Gaza in November 2008 came as no great surprise. Nor did his refusal to accept the 2011 UN report into the Mavi Marmara affair, which concluded that the Israeli blockade of the Gaza strip was legal, and raised “serious questions about the conduct, true nature and objectives of the flotilla organizers, particularly IHH” – a Turkish Islamist organisation supported by the government.

A report on Israel-Turkey relations prepared by the Centre for Political Research concluded that: “for Erdogan, Israel-bashing is a way of bolstering his status with Islamic and Middle Eastern states, which Turkey would like to lead.”

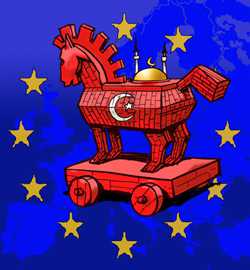

An Islamist axis led by Turkey? Only a few years ago the idea would scarcely have been feasible. Today the mere possibility represents one further obstacle on Turkey’s path towards full membership of the EU. For there is rooted opposition among a tranche of EU members to the very idea of clutching an Islamist viper to their Judeo-Christian bosom.

Chief among them is Germany. “Accepting Turkey to the EU is out of the question,” said Angela Merkel in 2009, and there is no reason to believe that she has changed her mind. Her chief of staff, Ronald Pofalla, said on his website: “I ask myself how a country that discriminates against Christian churches could be a member of the EU.” The most that German opinion-leaders would like to offer Turkey is “privileged partnership” in the EU.

France under President Nicolas Sakozy was equally rooted in its opposition to Turkey’s accession. With the change of president to socialist François Hollande, Turkey hoped, in the words of Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, that “a new course in Turkish-EU relations will gain momentum”. But Hollande, during his presidential election campaign, said that while France has long accepted the principle of Turkish accession to the EU, major conditions have not been met and may not happen for several years.

Austria – perhaps recalling that Muslim forces of the Ottoman empire twice stood at the very gates of Vienna, beseiging the city − have proved strong opponents to Turkey’s entry to the EU. The USA and the UK, on the other hand, with shorter memories, apparently discount the threat that Islamism poses to the West and remain strong supporters of Turkey’s bid.

But is Turkey as committed to joining the EU as it once was? After all, Turkey’s economy is booming, while the EU is in dire financial straits. Moreover, Kristina Karasu, writing in Der Speigel, points out that following the AKP’s overwhelming re-election in June 2011, Turkish desire for reforms has stalled.

“Even as Prime Minister Erdogan likes to position his country in the Arab world as a role model for Muslim democracy,” she writes, “thousands of Kurds, students and more than 100 journalists are sitting in jail in Turkey based on what are sometimes absurd charges.”

For the Turkish bid to be successful, EU member states must unanimously agree. In December 2011, a poll carried out across Austria, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain and the UK, revealed that 71 percent of those surveyed were opposed to the EU admitting Turkey as a full member.

A hesitant bridegroom and a bashful bride. The prospect of an early marriage is not bright.

About Neville Teller

Neville Teller is the author of “One Year in the History of Israel and Palestine” (2011) and writes the blog “A Mid-East Journal”. He is also a long-time dramatist, writer and abridger for BBC radio and for the UK audiobook industry. Born in London and educated at Owen’s School and St Edmund Hall, Oxford, he is a past chairman of the Society of Authors’ Broadcasting Committee, and of the Contributors’ Committee of the Audiobook Publishing Association. He was made an MBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours, 2006 “for services to broadcasting and to drama.”