I want to tell you a story. You don’t have to believe it. I didn’t at first, and it happened to me. It was years ago in Istanbul, at the end of a long evening down by the water at Besiktas, when we had all become as dreamy as the waters of the Bosphorus at that hour. I was aching for my bed, but the tide of the night was running towards an iskembe joint, and I could already taste the garlicky vinegar of the tripe soup on the air. I pleaded mercy – a godawful early start for Salonica – when a young guy at the edge of the group touched my arm. “If you are going to Salonica, you must eat the borek,” he said, and began to write down directions to the best bougatsatsidiko in the city.

He had never been to Thessaloniki himself, but his grandfather had been born there. Even his grandmother, who came from Hania, with all the Cretan pride that entails, had to admit that Salonicans made the best borek/bougatsa on the planet – the lightest, flakiest filo, just greasy enough to cut the goaty kick of the young mizithra cheese flecked with oregano and mint.

He handed me a napkin with a line drawn across it to show the sea, a fortress on a hill, a hamam with three domes, and between them the Turkish names of some streets.

But hadn’t Thessaloniki been Greek since December 1912? Hadn’t it been burned to the ground, bombed, rebuilt, knocked down and rebuilt again since then? Hadn’t it endured two world wars, various occupations, a civil war, a dictatorship and the worst that precast concrete can inflict? Hadn’t its Turks been sent back to the eternal exile of “home” and its Jews, the soul of the city, who made up the majority of its remarkable mix of peoples, been all but exterminated at Auschwitz?

None of this seemed to phase him. It should be there. “People still have to eat borek.”

Two days later, using his scribbled directions, I found a bougatsa shop just where he said I would, next to a patsas place that was still serving the Greek variant of that hangover tripe soup I had missed in Istanbul to the last of the night’s stragglers.

Greek troops arriving at Salonica, now Thessaloniki, in 1915The owner was a refugee, too. But his family had come from Smyrna, now Izmir in Turkey. His Borekci grandfather had taken over from a man who had been given the key by a blond-haired Turk the day he and his family were deported in 1924 with the last of the city’s Muslims. And yes, the bougatsa was fit for a bishop.

Greek troops arriving at Salonica, now Thessaloniki, in 1915The owner was a refugee, too. But his family had come from Smyrna, now Izmir in Turkey. His Borekci grandfather had taken over from a man who had been given the key by a blond-haired Turk the day he and his family were deported in 1924 with the last of the city’s Muslims. And yes, the bougatsa was fit for a bishop.

I took a photograph of the owner with two customers – one an Armenian Greek, the other a Cappadocian, though neither had set foot in the places they claimed to be from – and sent it to my friend in Istanbul. A few weeks later I received a reply.

He’d shown the photo to his grandfather, then well into his 90s. I’d got the wrong borek shop. The place never got sun like that in the morning.

I am telling you this story because to me it says a lot about the people who live in Salonica or have lived there, and people who have only inhabited the city in their dreams or in the stories of their parents or grandparents, but for whom it is still in some ways home.

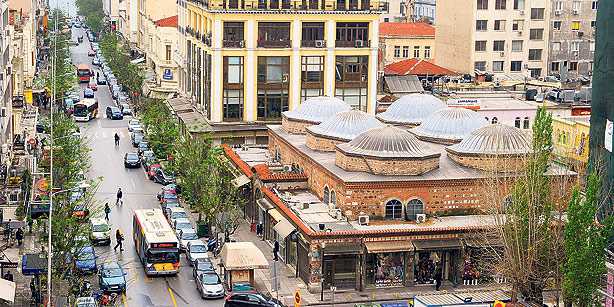

The guide books will tell you that Thessaloniki is Greece‘s second city, a port of a million people that doesn’t make the best of its spectacular setting and architectural heritage, its Byzantine churches lost in a permanent chaos of traffic and concrete.

I can’t say they are wrong. But then there is Salonica, Selanik, Solun and Salonika, the New Jerusalem, the city that was once a candidate to be the capital of a Jewish Promised Land, the second city of the Byzantine empire and later of the vast Ottoman emirate when it was up there with the Ming as the most dominant, dynamic dynasty on earth. This is the city that is the real capital of the Balkans, its missing heart, the lodestar of a whole swathe of the eastern Mediterranean, from the Adriatic to Alexandria. But all that post-Byzantine bustle was an embarrassment to the city and to Greece generally.

Arriving in Thessaloniki any time in the past 50 years, you would have found a city that had gone into exile from itself. This flight began the day the Greek army marched into Salonica in 1912 just ahead of the Bulgarians to “liberate” a city that wasn’t that Greek, and became practically pathological after the last transports left for Auschwitz carrying its Spanish-speaking Jews 32 years later.

The people who moved into their shops and apartments had themselves arrived, traumatised barely two decades earlier from Istanbul, Asia Minor, the Black Sea, Cappadocia or the Caucasus, or in endless refugee columns that had snaked from the Crimea, Bulgaria or Eastern Thrace. These new “old Greeks” of Magna Graecia were joined in the 1980s by Greeks from Russia, Tashkent, Kazakhstan, Georgia and Armenia, who now muddle along with the latest arrivals from Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia and more recently Libya, stuck in the island in the moat of Fortress Europe that is Greece today, unable to get into Europe proper, and too ashamed or broke to go home. Thessaloniki is such a place in exile that its biggest football team, PAOK, has been playing away from home for more than 80 years. Its real home turf is Istanbul – Costantinopoli – its colours shared with Besiktas.

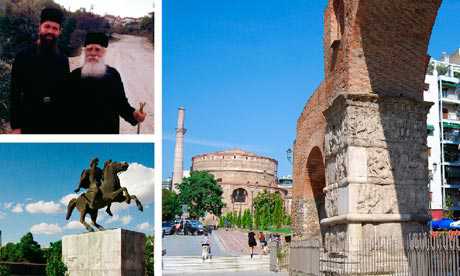

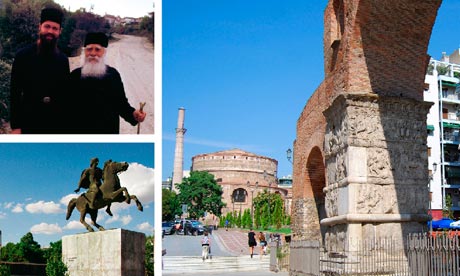

The church of St GregoryNothing is quite what it seems. To really see Thessaloniki for what it is, you have to see not just the living but the dead. You have to look out towards Olympus and the mists that roll in off the Thermaic Gulf and see Pierre Loti rowing Aziyadé away from her husband; or see the last true sultan, Abdulhamid II, step ashore into house arrest from the imperial caique with his harem and carpentry tools in tow (as well as being a paranoid, bloodthirsty tyrant, he was a very nifty cabinet maker).

The church of St GregoryNothing is quite what it seems. To really see Thessaloniki for what it is, you have to see not just the living but the dead. You have to look out towards Olympus and the mists that roll in off the Thermaic Gulf and see Pierre Loti rowing Aziyadé away from her husband; or see the last true sultan, Abdulhamid II, step ashore into house arrest from the imperial caique with his harem and carpentry tools in tow (as well as being a paranoid, bloodthirsty tyrant, he was a very nifty cabinet maker).

You have to imagine, too, those same women herded off a few years later into the saddest of travelling circuses ever to cross Europe. It is not for nothing that Mark Mazower subtitled his magisterial history of the place City of Ghosts.

This is a city of conspiratorial corners, where you cannot help turn detective as you climb up from Paralia through the Modiano market to Ano Poli and the city walls of the upper town, the Turkish quarter that looks so Greek. You don’t have to look too hard to see churches that have been mosques and mosques that are now churches, old women lighting candles at shrines to holy men that were both saints and dervishes, or find the Moorish mosque-cum-Andalusian synagogue that served the city’s Muslim Jews. Yes, you read right, Muslim Jews – the Ma’aminim or Donme, followers of Sabbatai Sevi. Thessaloniki did unlikely syntheses with the same ummatched elan as it do bougatsa. My God, they’ve tried, but no amount of wrecking balls or chauvinistic brainwashing has been able to destroy entirely the glorious diversity of its DNA. In any case, its unmentionable origins are laid out for all to see three times a day in its fantastic food, and in the songs that are sung in its skyladiko (literally “doghouse”) clubs and rembetiko tavernas every night.

There is no getting away, however, from the fact that Thessaloniki is still the most conservative, nationalistic city in Greece – where the Orthodox church could bring thousands on to the streets to threaten war with the fledging republic of Macedonia for trying to “steal the name of Macedonia” and the heritage of Alexander the Great. And there are plenty of Orthodox Taliban on the nearby monastic republic of Mount Athos, which has its embassy in the city, ready to pounce on any slackening of national-religious fervour. Which makes it all the more remarkable that earlier this year the radical winemaker and ecologist Yiannis Boutaris swept into office as mayor on a platform of getting Thessaloniki to come out about itself, to embrace the cosmopolitan city that in living memory had shop signs in six alphabets.

He first promised to build a new mosque and a monument to Salonica’s most famous son, Ataturk, and the Young Turks, whose revolution began there. And the doors should be thrown open to all the Jews, Turks and others who trace their roots to the city. The bishop of the city threatened to kill himself rather than swear Boutaris in and vowed to do everything in his power to stop this “Bulgarian traitor”, a reference to the mayor’s roots in the Latin-speaking Vlach minority. Boutaris branded him a “mujahideen” and took his own “cosmic vows”.

He’s going to need every bit of karmic help he can get. Thessaloniki has been run into the ground by a cabal of churchmen and extreme rightwing demagogues these past 20 years. The corruption and incompetence is on such a phantasmagoric scale that the city ran out of petrol to keep the handful of working dustcarts on the road. There is the small mattter, too that Greece is bankrupt. There is no better reason to bail out Greece again than to give Yiannis Boutaris a chance.

Essentials

EasyJet (easyjet.com) flies London-Thessaloniki in summer from £58.99 one way. Daios Luxury Living Hotel (+30 21 0923 6760; thessaloniki cityhotels.com) has doubles from €110

Seventy two fifth-graders from the Mandoulides elementary school, Thessaloniki will travel to Turkey, where along with 17 students from the Zografeion Lyceum will take part in the musical-theatrical performance, A Magical City, based on a fairy-tale by Helen Priovolos

Seventy two fifth-graders from the Mandoulides elementary school, Thessaloniki will travel to Turkey, where along with 17 students from the Zografeion Lyceum will take part in the musical-theatrical performance, A Magical City, based on a fairy-tale by Helen Priovolos

Greek troops arriving at Salonica, now Thessaloniki, in 1915The owner was a refugee, too. But his family had come from Smyrna, now Izmir in Turkey. His Borekci grandfather had taken over from a man who had been given the key by a blond-haired Turk the day he and his family were deported in 1924 with the last of the city’s Muslims. And yes, the bougatsa was fit for a bishop.

Greek troops arriving at Salonica, now Thessaloniki, in 1915The owner was a refugee, too. But his family had come from Smyrna, now Izmir in Turkey. His Borekci grandfather had taken over from a man who had been given the key by a blond-haired Turk the day he and his family were deported in 1924 with the last of the city’s Muslims. And yes, the bougatsa was fit for a bishop. The church of St GregoryNothing is quite what it seems. To really see Thessaloniki for what it is, you have to see not just the living but the dead. You have to look out towards Olympus and the mists that roll in off the Thermaic Gulf and see Pierre Loti rowing Aziyadé away from her husband; or see the last true sultan, Abdulhamid II, step ashore into house arrest from the imperial caique with his harem and carpentry tools in tow (as well as being a paranoid, bloodthirsty tyrant, he was a very nifty cabinet maker).

The church of St GregoryNothing is quite what it seems. To really see Thessaloniki for what it is, you have to see not just the living but the dead. You have to look out towards Olympus and the mists that roll in off the Thermaic Gulf and see Pierre Loti rowing Aziyadé away from her husband; or see the last true sultan, Abdulhamid II, step ashore into house arrest from the imperial caique with his harem and carpentry tools in tow (as well as being a paranoid, bloodthirsty tyrant, he was a very nifty cabinet maker).