The Wall Street Journal JULY 10, 2010

![The Submarine Deals That Helped Sink Greece 8 [SPARTAP1]](http://sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-AW167_SPARTA_NS_20100709200901.gif)

By CHRISTOPHER RHOADS

ATHENS–As Greece slashes spending to avoid default, it hasn’t moved

to skimp on one area: defense. The deeply indebted Mediterranean

nation, whose financial crisis roiled the global financial system

this year, is spending more than a billion euros on two submarines

from Germany. It’s also looking to spend big on six frigates and

15 search-and-rescue helicopters from France. In recent years,

Greece has bought more than two dozen F16 fighter jets from the

U.S. at a cost of more than EU1.5 billion.

Arne Lutkenhorst Among Greece’s questioned costs is more than a

billion euros on new submarines.

Much of the equipment comes from Germany, the country that has had

to shoulder most of the burden of bailing out Greece and has been

loudest in condemning Athens for living beyond its means. German

Chancellor Angela Merkel has admonished the Greek government “to

do its homework” on debt reduction. The military deals illustrate

how Germany and other creditors have in some ways benefited from

Greece’s profligacy, and how that is coming back to haunt them.

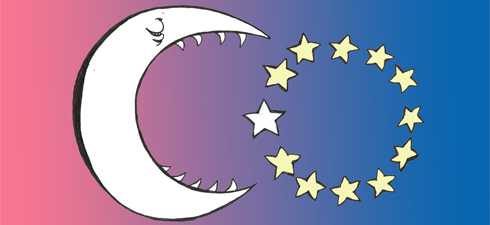

Greece, with a population of just 11 million, is the largest importer

of conventional weapons in Europe–and ranks fifth in the world

behind China, India,

the United Arab Emirates and South Korea. Its military spending is

the highest in the European Union as a percentage of gross domestic

product. That spending was one of the factors behind Greece’s

stratospheric national debt. The German submarine deal in particular,

announced in March as the country lurched toward bankruptcy, has

cast a spotlight on the Greek military budget and

on the foreign vendors supplying the hardware. The deal includes a

total of six subs in a complicated transaction that began a decade

ago with German firms. The arms sales are drawing heat from Turkey,

Greece’s neighbor and arch-rival. “Even those countries trying to

help Greece at this time of difficulty are offering to sell them

new military equipment,” said Egemen Bagis, Turkey’s top European

Union negotiator, shortly after the sub deal was announced. “Greece

doesn’t need new tanks or missiles or submarines or fighter planes,

neither does

Turkey.”

Greece’s deputy prime minister, Theodore Pangalos, said during an

Athens visit in May by Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan

that he felt “forced to buy weapons we do not need,” and that the

deals made him feel “national shame.” Other European officials have

charged France and Germany with making their military dealings with

Greece a condition of their participation in the country’s huge

financial rescue. French and German officials deny the accusations.

A spokesman for German Chancellor Merkel says the submarine transaction

was the culmination of an old contract signed long before Greece’s

debt crisis. In May, France’s defense ministry said Greek authorities

have confirmed their willingness to pursue talks on several

arm-procurement deals.

In May, Greece’s economic crimes unit began investigating all weapons

deals of the past decade–totaling about EU16 billion–to determine

if Greece overpaid or bought unnecessary hardware.

Bloomberg News Prime Minister George Papandreou and his government

have been chided over spending by Germany’s Angela Merkel. German

prosecutors are investigating whether millions of euros in bribes

were paid to Greek officials in connection with the sub deal. In

May, the chief executive of one of the German companies helping to

build the submarines, called

Ferrostaal AG, resigned amid the probe. For some prominent Greeks,

the latest submarine deal was the last straw. In late

April, Stelios Fenekos, a 52-year-old vice admiral of the 22,000-person

strong Greek Navy, resigned his position, bringing a three-decade

Navy career to an end. He says he did so to protest the Greek defense

minister’s decision to purchase the subs, as well as other decisions

taken in recent months that Mr. Fenekos considers “politically

motivated.” “How can you say to people we are buying more subs at

the same time we want you to cut your salaries and pensions?” says

Adm. Fenekos, in his first interview with a reporter. He was referring

to the government’s 5% cut in most pensions and even deeper slashes

to public-sector wages enacted in response to the crisis. The Greek

Navy, he says, cannot afford to maintain the additional submarines.

It currently has eight subs. A spokesman for the Greek Ministry

of Defense said Mr. Fenekos’ resignation was accepted. In stepping

down, “Mr. Fenekos did not refer to the submarine deal,” he said.

Greece became the first battleground in the Cold War, with the U.S.

backing anti-Communists in the Greek civil war in the late-1940s

against Communist insurgents. The conflict led U.S. President Harry

Truman, in 1947, to pledge unlimited military support for nations

under Communist threat, known as the Truman Doctrine. While the

rest of Western Europe used U.S. aid to rebuild its economy from

the second World War, in Greece, the emphasis was on building up

the military.

“Greece became the front line in the Cold War, and that began, right

then and there, the Greek economic crisis of today,” says Andre

Gerolymatos, a professor of Hellenic studies at Simon Fraser

University in Vancouver. By the mid-1950s, the U.S. pulled back

aid, much of which had been in the form of military hardware,

shifting much of the burden for Greek military spending to

Athens.

By this time, Greece’s worsening relations with Turkey led to yet

more arms spending. Despite being fellow members of the North

Atlantic Treaty Organization, the two nations are bitter rivals.

The discovery of oil in the northern Aegean Sea and disagreements

over territorial waters and airspace became the source of numerous–and

expensive–altercations between the two countries.

An incident in 1996, involving a Turkish ship running aground on a

rocky, uninhabited Greek islet, almost led to war. Greece later

that year announced a 10-year modernization program of its armed

services, costing nearly $17 billion. The U.S. over the years

catered to the two NATO members under a 7:10 ratio, meaning for

every $7 million dollars of equipment it sold to Greece it sold $10

million to the more populous Turkey. It was in that environment

that Greece in 1998 went shopping for submarines. It decided on

three German-built class-214 submarines, a state-of-the-art

diesel-electric powered vessel, with the option of buying a fourth–for

a total of EU1.8 billion. The first was to be built at the Kiel

headquarters of Howaldtswerke-Deutsche Werft GmbH, with the others

built at the affiliated Hellenic Shipyards SA, in Skaramangas,

Greece. The arrangement, called the Archimedes Program, would

preserve thousands of jobs

at the Greek shipyard. Greek officials in 2002 expanded it to

include the modernization of three older class-209 submarines–work

to be done at the Skaramangas shipyard using materials

and help from the Germans. The increase would cost another EU985

million.

The German side consisted of a company owned by German truckmaker

MAN SE, called

Ferrostaal, and Howaldtswerke-Deutsche Werft, now owned by ThyssenKrupp

Marine Systems AG. (MAN has since reduced its stake in Ferrostaal

to 30%.) The total cost of the new and renovated subs: EU2.84 billion.

As the military expenditures rose, Greece’s two main political

parties used them

as a political football, each trying to make the budget deficit

figures look worse when the other was in charge. When the Socialist

government first bought the submarines, it post-dated the accounting

for them to the day when the vessels were to be delivered, rather

than when they were purchased.

The government at the time was struggling to meet budget criteria

for entry into

the euro zone, which it joined a year behind other members in 2001.

Pushing back

the expenses saddled the bill with the Socialists’ successors, the

conservative New Democracy party, which came to power in March 2004.

The New Democracy government that year then used a similar tactic,

by

retroactively accounting for the expenditures on the date of purchase.

That inflated the budget deficits of the previous government–while

making it easier for the New Democracy government to meet its own

deficit goals.

Both accounting methods at the time were allowed by the European

Union. The resulting massive deficit revisions made in 2004 for the

previous years–4.6% of gross domestic product versus 1.7% for

2003–triggered an investigation in 2004 by Eurostat, the European

Union’s statistics agency, to understand what caused the revisions.

The findings did not result in any sanctions.

Military spending accounted for nearly a quarter of the difference

in the 2003 figures, and even more in revisions made on the deficits

for preceding years.

After the Socialist party, PASOK, returned to power in October 2009,

it made a similar maneuver: It announced the federal deficit was

much worse than the outgoing government had let on, mainly due to

public hospital debts, setting in motion the financial crisis.

Meanwhile, not one of the subs had been delivered. When Greek

officials traveled

to Kiel to test the first sub, called the Papanikolis, they said

that they found

that in certain sea conditions the submarine listed to the right.

“The Navy said

we cannot accept this sub,” said Mr. Fenekos, the admiral who

recently resigned.

“But the politicians did not want to stop it because they needed

the production for the workers in the shipyard here.” ThyssenKrupp

Marine Systems said the criticism was baseless and was made to delay

payment. By last fall, Greece had paid EU2.032 billion, about 70%

of the total owed. With the deal at an impasse, the German companies

cancelled the contract. Finally, in March, the two sides announced

they had begun negotiating a new deal. Instead of having three older

subs modernized, just one would be modernized, and Greece would buy

two additional new ones, bringing the total to six new submarines–costing

a total of EU1.3 billion.

Abu Dhabi MAR LLC, a shipbuilding company in Abu Dhabi, would buy

75.1% of the Greek shipyard, with the expanded submarine deal a

condition of the sale. The Greek government finally accepted the

sub, with the understanding it would immediately resell it. No deal

has been finalized.

Greece’s defense minister, Evangelos Venizelos, speaking to the

Greek parliament

in March, explained that the deal was an attempt to end the mess,

to “sever the Gordian knot” that the new government had inherited.

With 1,200 shipyard jobs at stake, Germany demanding concessions

on the complex deal, and Greece having already paid two billion

euros without receiving a single sub, the new arrangement was

necessary, he said.

But in February, just as a solution appeared to be at hand, German

prosecutors in Munich began turning up evidence of unsavory dealings,

according to records of their investigation.

Ferrostaal executives authorized payments worth millions of euros

to politicians

to win the initial deal in 2000, through a Greek company called

Marine Industrial Enterprises, according to the Munich prosecutor’s

records.

To do this, Ferrostaal used sham consulting contracts, according

to the records.

That company then distributed payments to “officials and decision-makers”

in Greece, according to the records. The investigation is ongoing.

No charges have been filed.

Adamos Seraphides, chairman of MIE Group Limited, a successor company

to a division of Marine Industrial Enterprises, said he doesn’t

believe that the company’s prior leadership was involved in bribery.

In March, police searched Ferrostaal offices, in Essen, seeking

evidence of bribe payments. In May, several executives stepped down.

“Ferrostaal will continue to pursue the intensive dialogue with the

state prosecutor’s office in Munich and has pledged full and

comprehensive support and

cooperation,” says a Ferrostaal spokesman.

A ThyssenKrupp spokesperson says the company got into the business

only in 2005,

when it bought Howaldtswerke-Deutsche Werft. Despite the tortuous,

decade-long journey of the submarine deal–and Greece’s precarious

financial standing–Germany stands ready for more business. Guido

Westerwelle, the German foreign minister, in February told a Greek

newspaper that Germany doesn’t want to force Greece to buy anything.

But “whenever it comes to the point when it’s ready to buy fighter

planes,” a European fighter-plane consortium, which Germany represents

in Greece, “wants to

be considered in the decision.”

A spokesman for Mr. Westerwelle says the minister didn’t discuss

fighter sales with the Greek government during the visit.–Alkman

Granitsas, David Crawford and

David Gauthier-Villars contributed to this article.

![The Submarine Deals That Helped Sink Greece 8 [SPARTAP1]](http://sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-AW167_SPARTA_NS_20100709200901.gif)