Sundays usually mean brisk business for Turkish hairdressers. In the town of Reyhanli, on the Syrian border, a small shop is bustling with excited future brides and their relatives waiting to be styled for weddings and engagement parties.

The owner, Hatice Utku, is perming the hair of a woman who looks unusually sombre. Unlike the other customers, she is not accompanied by family members. “A Syrian bride,” Utku explains, sounding slightly disgruntled. “We are getting a lot of those now.” One of her colleagues chips in: “They are stealing our husbands.”

It is three days since Aminah, 27, from Idlib in Syria, first met her 43-year-old Turkish husband-to-be through a matchmaker. “He divorced his first wife and wanted to marry again,” Aminah says timidly. “He has a house and a job in Ankara. My family in Syria has nothing left. He will provide for me.”

Her fiance, a businessman from Ankara, paid about 3,000 Turkish lira (£828) for the introduction to his bride, plus 5,000TL for expenses. The couple communicate through a translator. “He will learn Arabic,” Aminah says. Is she looking forward to her new home in the Turkish capital? She shrugs. “I am happy, I guess. I don’t know.”

Aminah is one of an increasing number of Syrian refugees who opt to marry Turkish men. Women’s rights groups are worried: “A lot of women agree to these marriages out of sheer desperation. All they think about is how to feed their family, how to make ends meet. These arrangements might seem like the only way out, and men exploit this,” says one activist from Gaziantep, who wished to remain anonymous. “At the same time, local women feel helpless and anxious about their own families breaking apart. Women on both sides of the border become victims this way.”

In Kilis, a town where Syrian refugees outnumber local people, a 43-year-old Syrian woman says aid workers from a faith-based charity pressured her to marry her daughter to a Turkish government official, arguing that the man was charitable, had “donated many biscuits” and that “she should be grateful for such a good offer”.

Dr Mohamed Assaf, who works at a Syrian-run medical centre in Kilis, says almost 4,000 Syrian women have married Turkish men in the town since he arrived in 2012. Dr Reemah Nana, a gynaecologist at the clinic, says patients with Turkish husbands sometimes complain about domestic violence, but in general, marriages are happy. Asked about sexual abuse, she concedes: “We hear of cases, but most women don’t want to talk about it.”

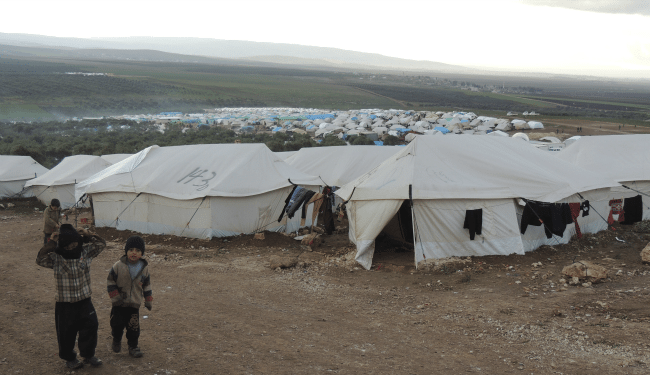

Turkish authorities put the number of Syrian refugees in the country at nearly 1 million, a figure projected to rise by the end of the year to 1.4 million. According to the UN high commissioner for refugees (UNHCR), women and children constitute 75% of refugees in Turkey, with under-18s accounting for 50%. In a 2013 report, the Turkish Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency stated that roughly a fifth of heads of household – inside and outside of refugee camps – were women. Human rights groups have repeatedly pointed out that women refugees from Syria are especially vulnerable, and that many face rape, sexual abuse and harassment. A recent UNHCR report also underlined the dangers facing lone women refugees.

Like many Syrian refugees, Aminah entered Turkey illegally and without a valid passport, making it impossible to register her marriage. The ceremony will be a religious one, performed by an imam, thus leaving her without any protection or rights in the event of a separation or her spouse’s death. According to Kemal Dilsiz, a matchmaker in a village close to the Syrian border, most Syrian women who marry Turks do so without legal registration. “None of these weddings are official since none of the women have passports,” he says.

The Syrian women that Dilsiz “introduces” to his Turkish customers usually come across the river Orontes, on floats, at 100TL a ride. “I married off around 60 Syrian girls,” he says, not without pride. “Men from all over Turkey call me, looking for a wife from Syria. They say Syrian women are more loyal, more obedient, that they don’t talk back.”

Paid matchmaking, illegal in Turkey, is a thriving business in the provinces bordering Syria. According to one hotel employee in Antakya, marriage tourism is common. “We have male Turkish guests from all over the country,” he says. “They come to look for a Syrian wife.”

“Human trafficking and all problems associated with it – abuse, rape and exploitation – have increased since 2012,” says the women’s rights activist from Gaziantep. “We hear of more and more cases of ‘temporary marriages’, basically sex work, but women are afraid to talk about this openly. It is worrying that the idea of temporary marriages is now being normalised in Turkey. It puts the veneer of respectability and religious approval on sexual abuse and exploitation.”

Dilsiz introduces girls to any man who can pay: “It costs 4,000TL for me to arrange a meeting. Then there are the men on the Syrian side, the wedding, the car – all in all it would cost you around 10,000TL to get married to a Syrian girl.” He claims that Syrian marriage impostors have damaged his reputation, and that he has been hesitant to suggest a “serious bride” for a while. “But if you don’t mind running that risk, I can get you a Syrian woman right now,” he says. “You can marry her for a few months, if that’s what you want.”

Outside a non-governmental organisation in Kilis, several women wait for the daily distribution of nappies and food, discussing wedding plans for their daughters. Hanan, 45, says her 23-year-old daughter will become the second wife of a 35-year-old Turk. “He promised to do the house and his car in her name. She will be better off that way.”

Amina, 60, disagrees. “Don’t marry your daughter to a Turk. I know a family who was promised the same thing, and their daughter was sent away after two months.” Hanan says she has little choice. “He will take care of her, she will be provided for.”

Turkish human rights groups warn that polygamy, outlawed in Turkey almost a century ago but still practised in conservative rural areas in south-eastern Anatolia, is on the rise. Second, third, or even fourth wives – called kuma in Turkish – lack legal protection and are especially vulnerable to abuse.

Fatma, 28, from Aleppo province, married her Turkish husband, a farmer, three months ago. She is his second wife. “His first wife is ill and does not want to have any more children,” she says. Fatma is pregnant with her husband’s seventh child. “I am very happy. His first wife is nice to me, she says she is glad that I am here to help her. We share all the housework.” She pauses. “Though it’s hard to share the man you love with another woman, but what can I do? It’s fate.”

Resentment is growing. Women in border towns and cities accuse Syrian women of luring away their husbands, saying their spouses routinely threaten them with taking a Syrian wife.

At the hairdressers in Reyhanli, several local women express their anger. “Syrian women have broken up many families here,” says Kadriye, 36, who owns a bridal wear business nearby. “Our husbands have become real beasts since the Syrians came. The men now make all kinds of excuses to bring in a second wife. They threaten us because of the smallest things: the food, the housekeeping, anything. Some take wives the age of their daughters.”

Hatice Utku nods. “Domestic violence has increased, too. Women put up with anything nowadays, just to hang on to their husbands. ”

The women’s rights activist explains a worrying trend: “Local women are anxious. The constant fear of losing their husbands puts a lot of pressure on them. Domestic violence, threats, psychological pressure and abuse from their spouses have increased. We notice a rise in mental illness, especially depression, but the topic is not being addressed by the authorities.”

She says her organisation tries to assist Turkish and Syrian women: “We do house visits where we discuss this issue with the women here. We try to convince them to put the blame where it belongs. In order to counter this male opportunism, women from both sides of the border need to stick together.”

Some names have been changed.