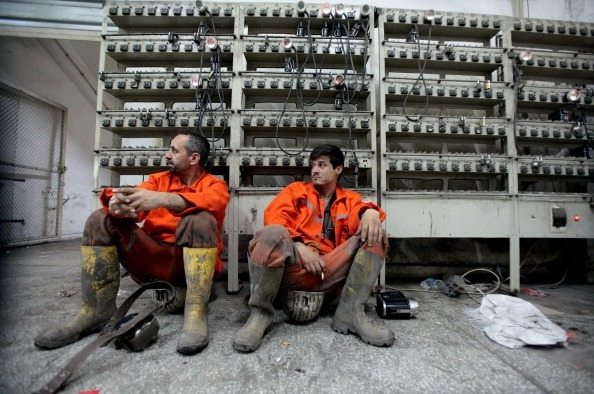

A protester is detained in front of the General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration headquarters in Istanbul on May 14.

A protester is detained in front of the General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration headquarters in Istanbul on May 14.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- NEW: Foreign Minister defends PM, says Erdogan “always feels the pain of the people”

- PM’s aide seen kicking a protester tells Turkish media he regrets not staying calm

- Minister says 283 are confirmed dead after fire inside a mine in western Turkey

- Protesters lay symbolic coffins at government buildings, rail against PM Erdogan

Soma, Turkey (CNN) — The image of an aide to Turkey’s Prime Minister kicking a man protesting the mine disaster that has claimed nearly 300 lives has prompted outrage — and has become a symbol of the anger felt against the government.

The incident occurred as Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan visited the western city of Soma a day after the devastating mine fire.

The man, detained by special forces, can be seen lying on the ground as the suited adviser to Erdogan, identified as Yusuf Yerkel by Turkish media and CNN Turk, aims a kick at him.

The shocking image outraged many in Turkey, prompting an outpouring of anger on social media, and is seen as symbolizing the increasingly polarizing impact of Erdogan’s authority on the country.

Turkish PM’s aide kicks a protester

Turkish PM’s aide kicks a protester

Mine disaster leaves families devastated

Mine disaster leaves families devastated

Mass funeral held for Turkish miners

Mass funeral held for Turkish miners

Turkey shaken by mine disaster

Turkey shaken by mine disaster

It’s been nearly a year since anti-government protests first roiled Istanbul, prompting a response from authorities that was widely criticized as heavy-handed.

Yerkel was quoted by Turkey’s semi-official Anadolu news agency as saying that he had been deeply saddened by Wednesday’s events. “I am sad that I could not keep my calm in the face of all the provocation, insults, and attacks that I was subjected to that day,” he reportedly said.

Besides the anger prompted by the photo, Erdogan’s speech Wednesday to relatives of dead and injured miners was seen as insensitive and drew scathing criticism.

As public anger mounted through the evening, hundreds took to the streets in anti-government protests in Istanbul and Ankara, with police answering, in some cases, with water cannons and tear gas.

In Ankara, the nation’s capital, some left black coffins in front of the Energy Ministry and the Labor and Social Security ministry buildings. Meanwhile, unions called for strikes across the country on Thursday.

At the mine, where what has become more of a recovery effort than a rescue continued, the mood was sullen, but there was little sign of the burning anger seen elsewhere over the accident.

Energy Minister Taner Yildiz said the number of coal miners confirmed dead had risen by one to 283, as of Thursday evening.

Three injured miners remain in the hospital, he said. The recovery operation is expected to continue overnight and into Friday.

A ‘sorrow for the whole Turkish nation’

President Abdullah Gul offered words of comfort as he visited the western city, a day after his premier attracted public ire.

The mine fire is a “sorrow for the whole Turkish nation,” Gul told reporters, and he offered his condolences to the victims’ families.

Onlookers listened silently until a man interrupted Gul with shouts: “Please, President! Help us, please!”

An investigation into the disaster has begun, Gul said, adding that he was sure this would “shed light” on what regulations are needed. “Whatever is necessary will be done,” he said.

He commended mining as a precious profession. “There’s no doubt that mining and working … to earn your bread underground perhaps is the most sacred” of undertakings, he told reporters.

Gul had entered the mine site with an entourage of many dozens of people — mostly men in dark suits — walking through a crowd of rescue workers who were standing behind loosely assembled police barricades.

Rescue and recovery workers retrieved more bodies Thursday from the still smoldering coal mine.

Resignation marked the workers’ faces after they had stood and sat outside the mine for hours, idle and waiting. Some of them passed the time talking on cell phones, others smoking or taking off their hard hats and burying their faces in their hands.

With hope of finding survivors nearly gone, it appeared there was little they could do.

Funerals amid grief

Smoke and fumes are hindering efforts to reach more of those still missing below the surface and lessen the chances that any more will be found alive, even in special “safe” chambers equipped with oxygen and other supplies. Fourteen bodies were found in one such chamber.

More than a day has passed since anyone was pulled out alive.

Rescuers saved at least 88 miners in the frantic moments after a power transformer blew up Tuesday during a shift change at the mine, sparking a choking fire deep inside.

Since then, the bodies of nearly 200 miners who were trapped in the burning shaft nearly a mile underground have been returned to their families.

Mine rescue efforts temporarily suspended

Mine rescue efforts temporarily suspended

Family: ‘Let this mine take my life too!’

Family: ‘Let this mine take my life too!’

Map of the mine location

Map of the mine location

Photos: Coal mine disaster in Turkey

Photos: Coal mine disaster in Turkey

Turkish opposition demanded mine reforms

Turkish opposition demanded mine reforms

“Enough, for the life for me!” yelled one woman — her arms flailing, tears running down her cheeks. “Let this mine take my life, too!”

Funerals took place Thursday in a community stricken with grief.

Autopsies on dozens of bodies revealed the miners died of carbon monoxide poisoning.

Erdogan said Wednesday that as many as 120 more were trapped inside the mine, though that was before rescue crews grimly hurried a series of stretchers — at least some clearly carrying corpses — past the waiting crowd.

In his much-criticized speech to the relatives of the dead and injured, the Prime Minister glossed over the issue of mine safety, describing the carnage they had suffered as par for the course in their dangerous business.

Apparently on the defensive, he rattled off a string of horrible past accidents, even going back to an example from 19th-century Britain.

As he took a stroll through the city, onlookers showered him with deafening jeers as well as chants of “Resign, Prime Minister!”

Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu defended the government’s response and Erdogan during an interviewwith CNN’s Christiane Amanpour on Thursday.

“All the efforts will be done to check what was wrong, if there was anything wrong during this disaster or before,” he said, stressing the country’s standards are “quite high.”

About Erdogan, Davutoglu said: “He was feeling all these pains in his heart. Everybody knows that our Prime Minister is always with the people, and always feels the pain of the people. Otherwise, he wouldn’t get such a high support in eight elections in (the) last 10 years.”

Scathing engineers’ accusations

A group of engineers investigating the cause of the inferno made a scandalous accusation.

“WHAT HAPPENED IN SOMA IS NOT FATE, IT IS MURDER,” a local branch of the Chamber of Electrical Engineers wrote in all capital letters at the top of its official statement Wednesday.

Although the group is not known for any party affiliation and comprises serious experts, such barbs have become common in a country riven with political division, where street protests and water cannons have become a familiar sight.

The statement also reflects the anguish that has shaken Turkey after what looks to be the deadliest mine disaster in its history.

5 worst coal mining disasters

1942 Honkeiko Colliery, China: 1549 dead

1906 Courrières, France: 1,099 dead

1914 Hojo Colliery, Japan: 687 dead

1960 Laobaidong Colliery, China: 682 dead

1963 Mitsui Miike, Japan: 458 dead

The latest death toll already tops a mining accident in the 1990s that took 260 lives.

The chamber of electricians also contradicted the official version of how the fire started, saying: “The fire was not caused by an electrical situation as presented to the public in the first statements.”

The assessment from inspectors from the chamber’s local branch in Izmir on what happened suggests negligence may have played a part.

“The inspection revealed that the systems to sense poisonous and explosive gases in the mine and the systems to manage the air systems were insufficient and old,” they said.

The blaze started as a “coal fire” at 700 meters deep, and then air fans pushed the flames and smoke farther through the mine, the chamber concluded. The ventilation was not corrected until “much later.”

The miners were trapped and inundated with smoke and fire.

Soma’s public prosecutor’s office has started an investigation of its own into the fire, Turkey’s semiofficial Anadolu news agency reported.

Political bonfire

The chamber’s accusations land on top of those already heaped on Erdogan’s government by his political opponents.

Opposition politician Ozgur Ozel from the Manisa region, which includes Soma, filed a proposal in late April to investigate Turkish mines after repeated deadly accidents.

He has said that he is sick of going to funerals for miners in his district.

Several dozen members of opposition parties signed on to his proposal, but Erdogan’s conservative government overturned it. Some of its members publicly lampooned it, an opposition spokesman said.

The mine, owned by SOMA Komur Isletmeleri A.S., underwent regular inspections in the past three years, two of them this March, Turkey’s government said. Inspectors reported no violation of health and safety laws.

Waiting on dead friends

For Veysel Sengul, a miner waiting by the mine’s entrance for more of his friends to emerge, the mourning may go on much longer than the three days of official grieving ordered by Erdogan.

After what’s happened, he said, he’ll never work in a mine again.

Rescuers haven’t given up hope that some miners reached emergency chambers stocked with gas masks and air and could still be alive.

But Yildiz, the energy minister, said “hopes are diminishing” of rescuing anyone yet inside the mine.

Sengul has already given up. The miner knows that at least four of his friends are dead.

Despair, anger, dwindling hope after Turkey coal mine fire

Diana Magnay, Ivan Watson and Gul Tuysuz reported from western Turkey; Ben Brumfield reported and wrote from Atlanta and Laura Smith-Spark from London. CNN’s Michael Pearson, Greg Botelho and Talia Kayali contributed to this report.

A protester is detained in front of the General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration headquarters in Istanbul on May 14.

A protester is detained in front of the General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration headquarters in Istanbul on May 14.