By Julia Harte at SolveClimate

Tue May 10, 2011 5:00am EDT

Installing PV arrays across one half of one percent of Turkey’s landmass could supply the nation’s current electrical capacity

By Julia Harte, SolveClimate News

ANTALYA, Turkey—Turkey’s weak policy support for solar power hasn’t stopped the sun-soaked southern city of Antalya from forging ahead with plans to exploit its solar resource — and to encourage other local governments to follow suit.

In April, Antalya opened its long-awaited “Solar House,” the first step in its push to become Turkey’s first and only solar city.

The environmental education center and renewable energy showcase boasts 24 one-kilowatt photovoltaic (PV) panels, among other clean energy solutions such as a windmill and a track that generates power from bicycles.

The model house cost about $600,000 and was 90 percent funded by Turkish companies and 10 percent by the United Nations Development Program. It will produce and store all the energy it consumes and feed excess power back into the grid — though it won’t profit from doing so.

The country’s energy authority doesn’t yet buy surplus electricity from small producers of solar power. This is partly why the cost of installing solar panels remains prohibitive for nearly all Antalya residents, local observers say.

“We need to show the Turkish people how we can produce solar energy, because it’s a very new concept for most Turks,” Mustafa Akaydın, the mayor of Antalya, told SolveClimate News in an interview.

According to Akaydın, the Solar House is “preparation” for its wider Solar City Green Antalya plan. Over the next decade and a half, the municipality hopes to transform itself into a clean energy dynamo on par with solar cities like Malmö, Sweden and Barcelona, Spain.

Though the financial support structure for the program is still fuzzy, the goal, at least, is clear: “We want to be the pioneers here and show the rest of the country about this solar potential,” said Akaydın.

Massive Untapped Potential

More than one million terawatt-hours of solar radiation hit Turkey each year. Solar leaders Spain and California, by comparison, receive approximately 0.8 million terrawatt-hours annually.

Theoretically, installing PV arrays across some 770 square miles — one half of one percent of Turkey’s landmass — could supply the nation’s current electrical capacity.

At present, PV systems account for just 5 megawatts of installed capacity. Turkey’s 8-gigawatt solar thermal capacity is seen as slightly more promising, but still accounts for less than 1 percent of the country’s overall energy production.

Antalya’s municipal government doesn’t yet have a goal for how much extra solar power capacity it hopes to add. For now, there is no accepted international definition of what it takes to earn the moniker of “solar city,” though several dozen such cities are said to exist throughout the world, including 25 in the United States.

The European Solar Cities Initiative, a project of the International Solar Energy Society, defines solar communities by their “large-scale integration of sustainable energy sources into city planning and urban concepts.”

In that spirit, Antalya is developing other renewable energies besides solar. A new waste management plant, for instance, will collect 60 percent of the city’s sewage and turn it into purified mud, which can then be converted into biogas.

The biogas-to-energy conversion facility is still under construction — a new component was finished the same week the Solar House opened — but in two months it will have a capacity of 2 megawatts, according to Münevver Ateş, environmental director at the plant. Once the facility is able to collect all the sewage in the city, its capacity will double.

More important than its capacity, however, is the fact that Antalya’s plant will produce all the energy it consumes, said Ateş, making it the only sustainable waste management plant in Turkey. “Many Turkish visitors come to study our example.”

Starting with the Rooftops

Antalya’s effort to boost its solar capacity will begin with a campaign to encourage individuals to install solar panels on their houses, though it won’t be easy.

The city currently has between 1 and 2 megawatts of solar power atop local residences, according to Ateş Uğurel, chairman of the Turkish Photovoltaic Industry Association, and founder of Temiz Dunya, the eco-architectural firm that designed Antalya’s Solar House. They may not be able to add much more because many Antalya residences are tall apartment buildings with small rooftops already full of thermal heaters, he said.

“There simply isn’t enough space.”

And then there’s the cost. The average Turkish house requires 3 kilowatts of electrical capacity. That amount of solar power costs approximately $10,000 to install, Uğurel said.

Widespread adoption should have an impact on costs. In about one month, Mayor Akaydın said he expects the passage of a municipal bylaw that would require future apartment buildings to be lit with PV panels.

After the residential campaign, the municipality will install solar power in city parks and gardens; increase its use in Antalya’s abundant greenhouses; and encourage local hotel owners to install solar power.

To date, the municipal government has installed 60 kilowatts of solar power — 24 kilowatts in the Solar House and the remainder in traffic lights.

Solar-Powered Tourism

“Antalya has the biggest solar potential in its tourism sector,” which attracts 50 million visitors a year, said Uğurel.

According to him, rooftops on the city’s hotels are big enough that installing PV panels would be a wise upfront investment for owners, providing free electricity once the systems pay for themselves.

Improving the solar capacity of Antalya’s hotels, Akaydın explained, might also draw more eco-tourists.

“There’s a trend in the world where tourists prefer an ecologically aware city as a destination,” he said. “Because of this, some hotel owners are now starting to use solar energy in new constructions.”

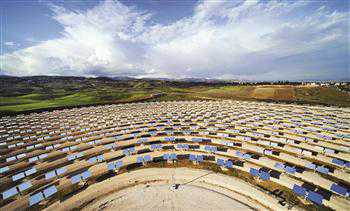

During the final stages of Antalya’s transformation into a solar city, the municipality intends to construct a solar farm and nurture a homegrown PV production industry.

Plans are already underway for a 100-kilowatt solar “forest” near Antalya, with “trees” composed of PV arrays designed by Mehmet Bengü Uluengin, an ecological architect and professor at Bahçeşehir University in Istanbul, who also designed the Solar House.

According to Uluengin, any city aiming to clean up its energy portfolio should start by reducing the amount of energy it consumes.

“That is where the low-hanging fruit are,” he said. “It is much cheaper, and more logical, to eliminate a kilowatt of energy use than to cater to its production via solar.”

Uluengin also pointed out that for solar to become widely used in Turkey the country’s entire energy transmission network would need to be upgraded to a smart grid that could accommodate not only millions of consumers, but also millions of producers.

“Antalya could become a solar city without necessarily using solar energy at high levels,” said Uğurel. “It could educate many people about solar, and use solar architecture to reduce the need for heating and cooling.”

No Political Allies

With the exception of Antalya’s municipal government, solar power has few political allies in Turkey.

The central government passed an amendment to Turkey’s renewable energy law at the end of 2010, introducing a new feed-in tariff for solar power of $0.133 per kilowatt-hour. That’s just under 10 euro cents per kilowatt, far less than the 45.7 and 33 euro cents that Germany and Spain, respectively, offer their solar producers.

In addition, the new amendment restricts the amount of solar power that can be added to the grid over the next two years. Only 600 megawatts of solar power can be connected by December 31, 2013, according to the rule.

“If there is anything positive about the amendment, it has helped to clear out the ‘speculative froth’ in solar,” said Uluengin.

“The [Turkish] Solar Expo in 2010 was packed with investors … This year, the place was virtually deserted. The only people remaining were those truly committed to solar — those with longer-term views and more realistic expectations of returns-on-investment.”

When applications for new solar power projects in Turkey are submitted later this year, it will present a clearer picture of just how much interest there is in developing the country’s solar resource. In the meantime, the government’s meager solar subsidies are discouraging foreign companies from investing in Antalya, Akaydın argued.

“There are a lot of people from all over the world, especially in Germany and China, who want to invest in Antalya’s solar projects,” he said. “The investors are ready, but the legislation is lacking. This isn’t just a task for our municipality; this is a national responsibility.”

The central government’s apathy toward solar power is reflected in Turks’ general lack of knowledge regarding solar.

“People still do not know of photovoltaic technology,” said Solar House designer Uluengin. “At trade fairs, we have people coming up to us pointing at PV panels and asking, ‘Where is the water storage tank for this thing?’ In Turkey, people know solar thermal. They don’t know PV.”

‘Very Healthy’

Still, Uluengin considers Turkey’s solar industry “very healthy” because it is being driven by small-scale and grassroots development.

“Only if an industry is viable on market forces alone will it be able to survive long term,” he said. In coming years, Uluengin believes that most PV systems in Turkey will be installed on the rooftops of commercial users, not in utility-scale applications.

Uğurel is also highly optimistic that the solar industry in Turkey can flourish without increased government incentives.

In a couple of years he expects solar power to reach grid parity, the point at which its price will rival that of conventional grid power. That’s largely because of the rising costs of fossil fuel electricity. Between the first half of 2008 and the first half of 2010, electricity prices climbed roughly 30 percent for Turkish households and industry, according to European Commission figures.

At the same time, the cost of PV systems is decreasing as more small Turkish entrepreneurs try their hand at producing panels, Uğurel said. “Every day, a new company enters the solar power sector.”

See Also: With No Policy Incentives, Turkey’s Solar Entrepreneurs Wait Out in the Cold Italy’s Green Giant Enel to Tap Turkey’s Geothermal Reserves Building of Turkey’s First Nuclear Plant, Sited on a Fault Line, Facing Fresh Questions