How To Play Turkey’s Shale Boom

By Chris Mayer | 03/13/13

I grabbed a taxi and headed up to the Le Meridien Hotel in Etiler, a neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey. I was on my way to have breakfast with N. Malone Mitchell III. He is the CEO, chairman and 40% owner of TransAtlantic Petroleum (TAT).

Malone’s company is the best way I’ve found to play a fascinating emerging energy story. It comes with risk, but offers a potential two–five times return on your money over the next few years…

Let me start with the big picture in Turkey.

The country sits on large untapped resources of shale gas. Nobody yet knows just how much natural gas Turkey might hold. One guess puts Turkey’s shale gas reserves at 20 trillion cubic meters. A fraction of that in Ukraine drew a $10 billion investment from Shell last month.

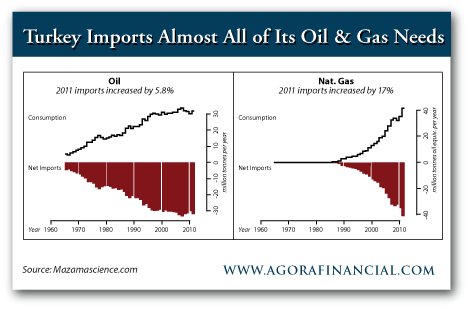

The irony is that Turkey depends heavily on expensive imports for both oil and gas. The two nearby charts tell you all you need to know. The first shows you how Turkey imports nearly all of its oil needs. The second shows you the same story for natural gas with an even steeper curve.

On the day of my meeting with Malone, Reuters released a story on Turkey’s gas potential. Malone got it on his phone while we were eating breakfast and showed it to me. A key excerpt:

With domestic gas consumption rising and [Turkey’s] geographic location meaning it is also well placed to supply international markets, major exploitable reserves could be a game changer for Turkey’s economy and highly lucrative for whoever finds them.

“We are keen to exploit this method and we must make economic use of shale gas,” energy minister Taner Yildiz told Reuters, saying it would be a priority for the near future.

This sets up the macro appeal of TransAtlantic. The other part of the appeal is in the micro, which begins with the talented Mr. Mitchell himself. He is a self-made oil and gas billionaire, a successful builder of companies. He is also, as I noted above, a big shareholder. And he has been buying more of late.

I’ve been following TransAtlantic for a few years now. It has been a longtime holding of my Mayer’s Special Situations newsletter. I share it with you here because it is one of the most intriguing ideas I have in Turkey and a good way to get exposure to a unique energy story.

It has not been a happy story to date. Over breakfast, Malone and I talked about the challenges TAT has had so far.

There has been a big learning curve in figuring out the geology. In many ways, TransAtlantic’s experiences mimic those of other successful unconventional plays. “It can take two years of failures before it all comes together,” Malone said.

There has also been the challenge of finding the right mix of people and getting the right systems in place. Malone told me about the intricacies of Turkish tax accounting, for instance. And he related some stories about personnel issues.

It is always easier to draw up the blueprint than to put it into action — especially in emerging markets. On the positive side, Malone said doing business in Turkey was as easy as doing business in Texas or Oklahoma from a regulatory point of view.

And though there have been setbacks, the plum of Turkey is as ripe as when Malone got involved in March 2008. He said Turkey then was like Texas in 1938 — a practically virginal land flush with oil and gas possibilities.

I asked him if he was still as excited about it as he was then. “Yes,” he said, “but I wish we knew then what we know now. Knowledge comes at a price.”

Frustrated by delays in ramping up production, the market has all but abandoned the shares. They now languish at around $1. Even just the value of its proved reserves — the so-called SEC PV-10 value — is about $1.75 per share (pretax). That gives the company no credit for whatever lies in its 5 million acres of underexplored land area. Yes, 5 million acres.

I asked Malone what he thought the market was missing with TransAtlantic.

“Well, the market thinks we aren’t going to do anything,” he said, thinking about that languishing share price. “The truth is if we weren’t a public company, I’d be fine about where we are.”

Indeed, the company is in a good position in a strategic sense. It has those 5 million acres locked up on long-term leases. It was early enough that it grabbed some of the best acreage. There are only three oil companies of consequence in Turkey: the national oil company, a privately held oil company and TransAtlantic. Everybody who comes after gets the crumbs left by these three.

Besides, TransAtlantic is already doing its bit to provide oil and gas to Turkey’s thirsty industrial base. In the Thrace Basin, TransAtlantic gas supports the city of Bursa. About 60 miles southeast of Istanbul, the Ottomans captured the city in 1326 and made it their first capital. Surrounded by forested hills and fruit orchards, it was once a Silk Road city. Today, there are nearly 2 million people in Bursa and it is home to thriving automotive and textile industries.

And there are a couple of big catalysts on the horizon that could make 2013 the year when the cards finally turn up right for Malone and his fellow shareholders.

First, Turkey’s unconventional oil and gas plays are getting more attention. Just a couple of days after our meeting, Malone would attend Turkey’s first shale gas and oil conference at the Bilkent Hotel in Ankara. There is an excitement in the air about what could happen in Turkey. And it is still very early.

The buzz could help Malone as he is trying to nail down a joint venture to accelerate the development of TransAtlantic’s acreage. The JV, Malone has said before and repeated at breakfast, could be as big as the sale of Viking (the company’s oil field services arm). For reference, this sale brought TransAtlantic $164 million, gross. As the whole market cap of TAT is only about $370 million, a JV that brought in that kind of cash would be huge. (And it is gravy on top of the $1.75 SEC PV-10 value I mentioned earlier.)

Second, the company is drilling some potentially high-impact wells. We should get the results on these wells within in the next six months. Malone was optimistic that these would bring strong results. Exciting results here could also light a fire under the stock.

I was glad to meet up with Malone. I have confidence he will figure it out and make it work. I think he is honest. He also owns a bunch of stock — an owner-operator, for sure. His track record of success is beyond dispute. All in all, a good mix, in my experience.

Reflecting on what TAT is building, I thought about how a bigger oil outfit will one day want to own it all. “Someday, somebody is going to want to write you a big check,” I said.

Malone said nothing, but his expression and his eyes told all. Exactly, they seemed to say. Exactly.

Sincerely,

Chris Mayer

Read more: How To Play Turkey’s Shale Boom http://dailyreckoning.com/how-to-play-turkeys-shale-boom/#ixzz2NUtPxnh0