By Nicola Stanbridge

Today Programme

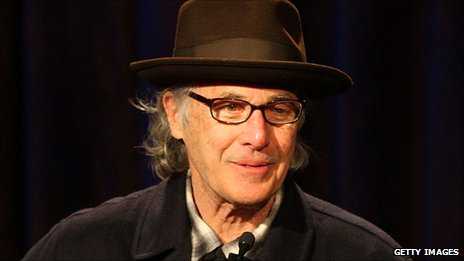

The guitarist Ry Cooder is most famous for his Buena Vista Social club recording, which he used to highlight his opposition to America’s trade embargo on Cuba.

In his new album he continues his political stance, claiming he will use his music to take on bankers and give voice to “ordinary working people”.

Pull Up Some Dust And Sit Down completes the circle with the musician’s first albums, which covered songs by Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly that evoked the desperate times of The Great Depression.

The opening track on your album is a song about bankers. How do you see your role – venting spleen, recording events, or as a modern day protest singer?

All those things are good. I don’t look at it that way, though. I’m an older guy now and I’ve been making records for so darn long, I look upon it as the life that I have. As Albert Einstein used to say, you do the best you can with what you’ve got.

What have the bankers done to you?

This is déjà vu – what caused the great depression has caused it all over again. The banking laws that FDR put in place in the 1930s worked very well until it was all deregulated during Reagan’s time. So now, 40 years later, we have this problem that nobody can solve.

So what the Republicans were trying to do over this period, wasn’t just to deregulate banking so that you could have unlimited profits. What they wanted was a return to a period of “pristine capitalism” when there were no unions, and there was no labour movement and there were no protections for the working people and profits were maximised.

It was a wonderful time for the working elite. This is what they’re trying to recreate and, man, they’re succeeding.

So it’s not the bankers themselves – although, of course they’re driven mad by their greed for money. And I’m sorry for them because that’s a crappy kind of lifestyle to have. How many BMWs do you need? How many Rolex watches you gonna wear in your lifetime, for crying out loud? What is it about that kind of desire? I don’t understand it.

In another song you dream of sending in Jesse James to sort out Wall Street. And you say “my 44 will do the talking”. I didn’t think violence and inciting hatred were allowed in America…

Well, see, the point here is that Jesse James was a primitive white man from the 19th Century. And in those days the hero was a one-man, one-gun hero. It’s a very popular American myth.

But what Jesse doesn’t realise [in the song] is that while he’s been up in heaven, the forces massed against him… He can’t overcome the growth of the corporate, military-industrial equation. He can’t walk down Wall Street and shoot up the place. No-one would even pay attention to him. The hero is outnumbered and outgunned. The wagons are circling, but what’s he going to do? What’s anyone going to do?

Do you own a gun?

No! No guns please!

My neighbour does, though. He told me so. He says to me, “my guns are in a bomb-proof safe”. I said, “what are you preparing for?”. He said, “when the zombies come.” That was the end of that conversation.

Tell us the story of Quicksand

Well, in the Sonoran desert, right around the US-Mexican border, the temperatures get up around 140F (60C) . You can’t live in that kind of heat, but there’s a trail leading from the Mexican side through Arizona. It’s called the Devil’s Highway and it’s been a migrant trail for 200 years.

People go out there and try to do it on foot, but if you make one mistake and go five minutes out of your way, you become disorientated and dehydrated. And they find these mummified bodies out there. The heat has just baked them through. And the people who live through it often refer to having a vision of the Virgin of Guadalupe flying overhead. This is a very common vision when the dehydration sets in.

So in the song the person says, “I see in my mind my mother, at home. And now I’m seeing the Virgin – take a message back to my home.”

What’s your take on immigration to the US?

It’s been a political issue in California for hundreds of years. We’ve had migrant workers here for almost 300 years – Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Mexican, Italian… my own grandfather.

Would you say the economy is dependent on immigrants?

Oh, totally. But in political times, you will have the forces of repression wanting to say, “hey, they’re taking your jobs, send them back”. We had a Chinese expulsion, Japanese expulsion. Woody Guthrie wrote a great song about deportation.

They’re playing political games, but a terrible price is being paid by people.

It’s often the case, though, that immigrants are forced to take the tougher jobs…

Sure, immigrants will do work that no-one else will do. There was even a movie about it – A Day Without Mexicans. In Los Angeles everything would come to a screeching halt.

You seem to favour stories about unlikely heroes – Harry Dean Stanton was one in Paris, Texas. Can we see thematic links in your work through time?

I suppose you can. I always say I’ve got three ideas and I keep recycling them.

What are the three ideas?

I forget what the other two are – but the bottleneck guitar was a nice thing I was introduced to. Records were my first teachers, and then people showed me how. I asked [pioneering steel guitarist] John Fahey, “what is that sound?” and he said, “well, you get a bottle, you put it on your little finger and you play”.

I had a lot of luck in meeting great musicians who were kind enough to show me things. Otherwise, I don’t know what I’d be doing today. Probably sacking groceries. I wanted to be a car pinstriper but there was nobody to teach me how to do it. So I said, “music’s good too. I’ll do that maybe, since I can’t work out how to do this pinstriping”.

Do you ever find yourself trying to recapture the public acceptance you had for Buena Vista Social Club?

Well, those master musicians of Cuba were a revelation to many people. To the non-Latin people who bought that record in great numbers, this was a door opened. This music, the sound of Cuba coming through the voices and the artistry of these older masters.

They had a “pre-media mind”. Before radio, before television, minds were formed by other kinds of human association and music. That can never be recaptured. So that album is one of those “adios” experiences. Wave goodbye, it’s the last remnant of this sound. The record was successful for that reason.

www.bbc.co.uk, 24 September 2011