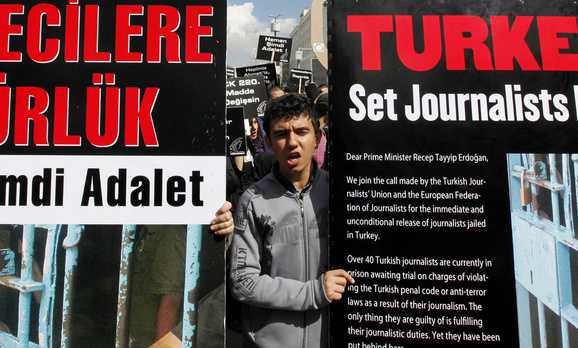

Turkey holds a notorious world “championship” title: it’s the country that keeps the largest number of journalists behind bars. And no one in the world no longer questions whether Turkey is being done injustice.

About This Article

|

Summary : Kadri Gursel writes that by criminalizing any press article that seems sympathetic to the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), the Turkish government worsens its image as a leading violator of press freedom.

Author: Kadri Gursel |

All major international groups advocating press freedoms agree that Turkey fully deserves the championship in imprisoning journalists.

Most recently, the World Press Freedom Index 2013, released by the Paris-based Reporters Without Borders (RSF), listed Turkey among the worst offenders, ranking it 154th among 170 countries. Thus, Turkey fell six places down the ladder compared to last year.

The RSF said Turkey is “currently the world’s biggest prison for journalists” and that the imprisoned journalists include “especially those who express views critical of the authorities on the Kurdish issue.”

To get a better idea of the situation, one should note that Finland, which topped the list as the country where the press enjoys the greatest freedom, had a violation score of 6.38, while Turkey got 46.56. And Sudan, ranked 170th at the bottom of the list, scored 70.06.

Turkey’s bad grades led the RSF to place it in the category of countries where press freedom is in a “difficult situation.”

The report stressed that, “The state’s paranoia about security, and itstendency to see every criticism as a plot hatched by a variety of illegal organizations, intensified even more during a year marked by rising tensions over the Kurdish question.”

Earlier, on Dec. 1, 2012, the New York-based Committee for the Protection of Journalists (CPJ) released a report on jailed journalists around the world and declared Turkey the champion with 49 journalists behind bars. Iran came second with 45 journalists in prison, followed by China with 32.

Obviously, the situation poses a grave image problem for Turkey and its leadership at a time when they claim the country’s democracy is an example for the Middle East.

The Turkish leaders, however, seem to believe they have found easy short cuts to supposedly manage this image problem.

A persistent, systematic rhetoric claiming that the imprisoned journalists are in fact terrorists used to be one of their methods.

They must have decided that this was not convincing enough because they are now accusing international press groups which raise the problem of Turkey’s jailed journalists of “collaborating with terrorists” and “writing made-to-order reports.”

Take, for example, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Speaking at his party’s parliamentary group meeting last week, he said: “Supporters of terrorism are in prison holding press cards. The chap gets caught with a gun, gets caught for killing a member of the security forces. And then what does he say? That he is working in the press. international organizations that say we have a negative attitude towards the press have gone as far as to issue made-to-order declarations depicting developments in Turkey in a negative light.”

In early December, Deputy Prime Minister Bulent Arinc told a visiting delegation from the International Press Institute (IPI) that not more than three journalists were imprisoned in Turkey.

In March 2012, Minister in charge of EU affairs Egemen Bagis argued on the BBC’s Hard Talk show that no Turkish journalist had been imprisoned for practicing his or her profession, and that those in jail had landed there for crimes such as murder, bank robbery and sexual assaults.

Indeed, international press freedom groups assume a great responsibility when they take on the arduous task of determining how many journalists are behind bars and whether they have been imprisoned in relation to their professional activities or for other offenses.

To defend as “journalist” a person standing trial for non-journalistic activities that constitute a genuine crime would before all damage the credibility of those organizations.

In a special report released last October under the title of “Turkey’s Press Freedom Crisis,” the CPJ said it was able to establish that 76 journalists were behind bars in Turkey, and that 61 of them had been imprisoned in relation to their professional activities. The situation of the others, it said, remained under examination.

Two months later, the CPJ unveiled its “2012 Prison Census” report, which revised the number of Turkey’s imprisoned journalists down to 49 as some were released in the meantime.

The fact that the overwhelming majority of journalists in Turkey’s prisons are Kurds is not a coincidence. Those journalists work for media outlets that support the Kurdish movement. Naturally, political activists have the right to do journalism on a selective agenda as long as they respect professional ethics.

The problem in Turkey, however, stems from the way the judiciary and the security apparatus regard journalistic activities that sympathize with the ideological and political line of the PKK, considered to be a “terrorist organization.” They tend to directly criminalize that type of journalism as “terrorist organization activity” and those journalists as “members of a terrorist organization.” And this propensity, which results in restrictions on press freedom, is backed by the government.

When more than 30 employees of the Dicle News Agency and the Ozgur Gundem newspaper were arrested in late 2011 on grounds they belonged to the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK), an outlawed Kurdish organization, the prosecutor who drew up their indictment listed basic and simple journalistic activities as evidence of their membership in a terrorist group.

To convince the international community that the imprisoned journalists are terrorists drawing on this legally flawed approach of the Turkish judiciary is impossible.

It seems government officials are now attempting to discredit those who refuse to be convinced by Turkey’s official reasoning.

An extreme example of those attempts came early last week when Star and Yeni Akit, two newspapers close to the AKP government, published reports alleging that the RSF had provided financial support for members of Turkey’s outlawed Marxist-Leninist Communist Party (MLKP).

The RSF rejected the allegations as “grave, disgraceful and absurd.”

In an article addressing those newspaper reports and Erdogan’s remarks, CPJ director Joel Simon wrote:

“In indictment after indictment reviewed by the CPJ, prosecutors have said that journalists who express dissenting political views are being directed by terrorist groups. Thus, the government reasons, they are themselves terrorists.

‘’These kind of attacks do nothing to change international public opinion, which is united in the view that Turkey is the world’s worst jailer of the press. In fact they reinforce the perception that an intolerant government deliberately conflates critical expression with terrorism in order to intimidate its perceived opponents.”

Kadri Gürsel is a contributing writer for Al-Monitor’s Turkey Pulse and has written a column for the Turkish daily Milliyet since 2007. He focuses primarily on Turkish foreign policy, international affairs and Turkey’s Kurdish question, as well as Turkey’s evolving political Islam.