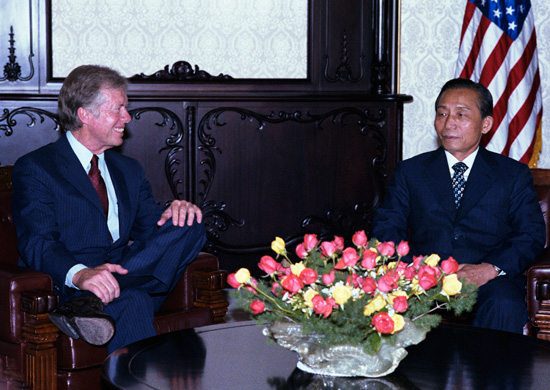

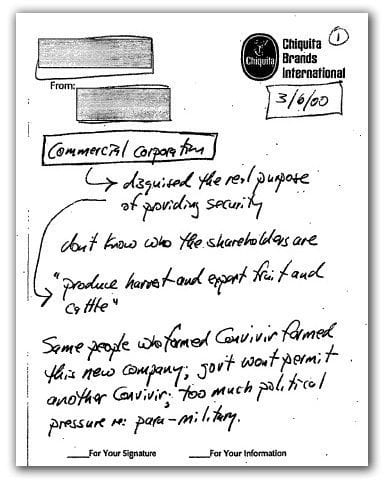

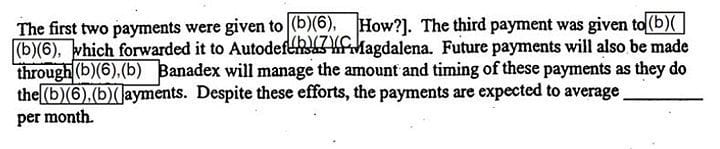

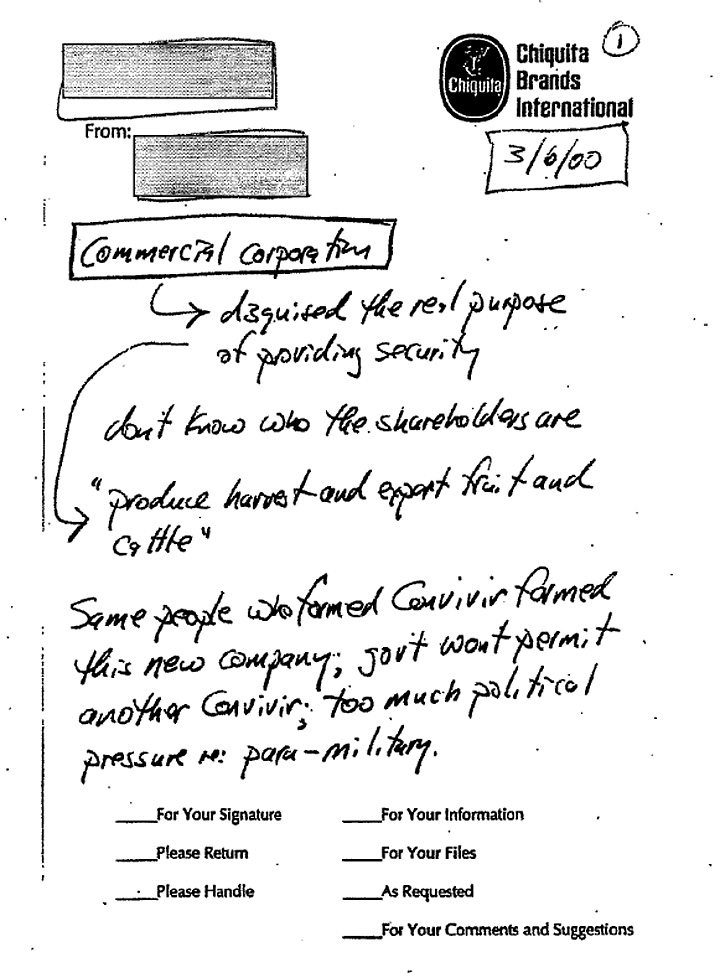

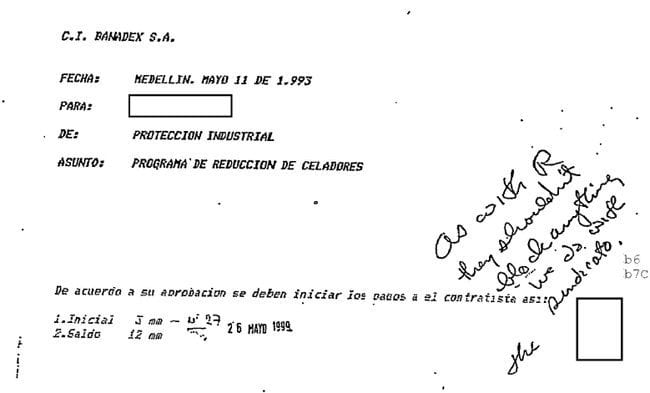

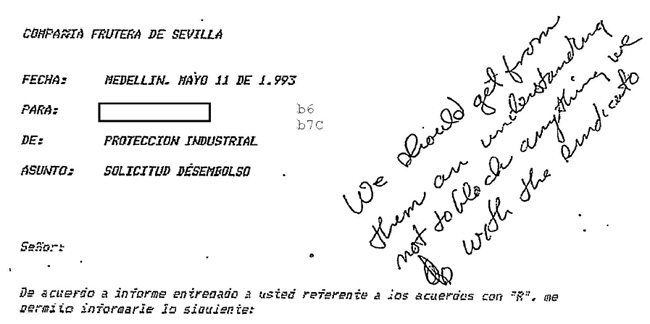

The Carter-Park summit meeting on June 30, 1979. The smile on Carter’s face belied the deep divide between the two leaders over keeping U.S. forces in Korea and human rights. Four months later, Park would be assassinated by the head of the Korean CIA.

Courtesy: Jimmy Carter Library

How Do You Solve a Problem like (South) Korea ?

U.S.-ROK Relations during the Carter Years Faltered over Troop Withdrawals, Human Rights, an Assassination, and a Coup

Carter Faced Pushback from South Korean Leaders and His Own Top Advisers

Posted June 1, 2017

National Security Archive Briefing Book No. 595

Edited by Robert A. Wampler, PhD

For more information contact: Robert A. Wampler, 202/994-7000 or wampler

Washington, D.C., June 1, 2017 – President Jimmy Carter entered office in 1977 determined to draw down U.S. forces in South Korea and to address that nation’s stark human rights conditions, but he met surprising pushback on these and related issues from both South Korean President Park Chung Hee and his own top American advisers, as described in declassified records published today by the National Security Archive at The George Washington University.

Carter made no secret of his deep misgivings about Park’s suppression of his political opposition. When the two met for a summit in June 1979, Park attempted to turn the tables, lecturing Carter rhetorically: “If dozens of Soviet divisions were deployed in Baltimore, the U.S. Government could not permit its people to enjoy the same freedoms they do now.”

At the same time, senior U.S. officials including Cabinet officers tried to put the brakes on U.S. troop withdrawals and other policy initiatives such as holding tripartite talks with the two Koreas. Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Michael H. Armacost complained to Defense Secretary Harold Brown before the summit that the latter was a “lousy idea,” a “loser” and “gimmicky.” The president faced similar resistance from a range of American officials on the ground in South Korea.

Carter was forced to postpone troop reductions for a time while continuing to press for political liberalization. But his challenge grew appreciably greater after Park’s October 1979 assassination by of the head of the Korean CIA, and a subsequent coup in December of that year by strongman General Chun Doo Hwan.

How Do You Solve a Problem like (South) Korea? The Carter Years

By Robert A. Wampler, Ph.D.

It should be no surprise that events on the Korean peninsula have presented early challenges for the Trump administration.[1] History shows that the combination of North Korean provocations and South Korean political crises has repeatedly confronted the U.S. with difficult policy choices. Previous electronic briefing books posted by the National Security Archive have addressed the limits of military options against North Korea [see EBB 322], the difficulties in understanding Pyongyang’s actions and goals [see EBB 421], and U.S. efforts to rein in South Korea’s nuclear weapons program [see EBB582 and EBB584].

For the Carter administration, the rocky course of Korean relations moved from the deep divide between Seoul and Washington created by Carter’s determination to withdraw U.S. forces and his criticism of Park Chung Hee’s human and political rights abuses, to the assassination of Park and subsequent military coup, followed by the rise of coup leader Chun Doo Hwan to the presidency and U.S. concerns over his authoritarian regime centering on the looming execution of South Korean political dissident Kim Dae Jung.

The historical backdrop to the documents posted here today can be sketched quickly.[2] President Carter entered office in 1977 determined to draw down U.S. forces in South Korea, and deeply concerned about Park Chung Hee’s suppression of political opposition. Both of these issues imposed immense strains on the alliance during Carter’s term in office. Carter faced significant push-back on the troop withdrawal issue not only from Park, but also from his senior advisors, particularly his secretaries of state and defense, as well as senior U.S. military officers in Seoul, who seized upon new intelligence estimates that showed a much stronger North Korean military capability to argue against the withdrawals.[3]

Following a tense and contentious summit meeting with Park in June 1979, the U.S. announced that further withdrawals would be put on hold until 1981. For his part, Park agreed to pursue increased military spending and to take steps to release political prisoners, though he continued to press the U.S. not to criticize publicly his actions against the political opposition, arguing that if given sufficient “running room” he would try to avoid “extreme” actions. (See Document 10)

Park would have little time to take any steps to address U.S. concerns, however, for on October 26, 1979, the director of the South Korean CIA would assassinate him during a dinner which was marked by intense and bitter arguments over Park’s handling of political discontent. In the aftermath of the assassination, once the identity of the assassin was determined, U.S. concerns centered on ensuring that this shock to the Korean political system did not result in political instability that could undermine democracy or tempt North Korea to further shake up conditions on the peninsula.

Hopes for an orderly political transition were dashed, however, when a group of “Young Turk” South Korean political officers, led by ambitious Korean Army general Chun Doo Hwan, staged a coup on December 12. In its aftermath, the limits on U.S. ability to influence political events in South Korea become ever more evident, as Chun, using his authority under martial law, imposed his own crackdown on political dissent, including the arrest of Kim Dae Jung, which was the spark that set off the May 1980 Kwangju uprising. The Chun regime brutally put down this uprising, and many South Koreans still see the U.S. as complicit in the crackdown because of claims made by the Chun government of U.S. support. Kim Dae Jung would be sentenced to death for his alleged role in fomenting the Kwangju uprising, and U.S. efforts to secure leniency for Kim would drive much of U.S. diplomacy with the Chun government (Chun, despite denials of political ambition, would be elected president in August 1980) until the end of the Carter presidency. It would be left to the incoming Reagan administration, which entered office determined to restore the alliance relationship, to finally secure commutation of Kim’s sentence.[4]

The documents posted here today come primarily from the Pentagon records of Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, and are supplemented by documents from the Digital National Security Archive collections on U.S.-Korean relations, as well as files obtained from the U.S. National Archives. As secretary of defense, Brown had the unenviable task of being Carter’s point man on defense issues in dealing with Park and then Chun. His role was to advance U.S. policy goals that were less than attractive to the South Korean leadership, as well as to advise President Carter on policy options that the president would find less than ideal.

Among the insights provided by these documents are these:

General John Vessey, the senior U.S. military officer in Seoul, described Park Chung Hee to new president Jimmy Carter as “a lonely man” who seemed to be “withdrawing more and more into himself.” [Document 1]

Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Michael H. Armacost called Carter’s idea for tripartite U.S.-ROK-North Korea talks a “lousy idea,” a “loser” with “atrocious” timing with little chance of success, possibly “ginned up” by the White House PR staff as a Camp David-style TV “spectacular.” [Document 4]

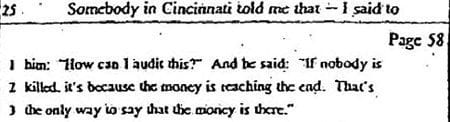

During their summit meeting, Park lectured Carter on human rights: “If dozens of Soviet divisions were deployed in Baltimore, the U.S. Government could not permit its people to enjoy the same freedoms they do now. If these Soviets dug tunnels and sent commando units into the District of Columbia, then U.S. freedoms would be more limited.” [Document 9]

Pentagon analysis of the situation immediately following Park’s assassination warned about the challenges facing the U.S. in trying to influence political developments towards greater democracy, arguing that the U.S., through “sensitive and judicious advice,” may be able to affect developments at the margins. In the short run, Washington needed “to avoid even the appearance of manipulating a puppet.” [Document 11]

South Korean General Lew found it conceivable that a “temporarily deranged” KCIA Director Kim Dae Kyu had decided to kill Park, driven by fears he was going to be replaced because of his “incompetence.” [Document 12]

After the December 12 military coup, Ambassador Gleysteen’s gloomy assessment spoke of how U.S. “missionary work” to guide the new government “seems washed down the drain.” [Document 13]

One Pentagon official referred to coup leader Chun Doo Hwan as the “Pete Dawkins” of the ROK army, a reference to a well known Army officer, who served in Korea in the early 1970s, because of his rapid rise through the ranks and professional achievements. [Document 14]

National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski warned the South Korean ambassador that Chun must avoid letting the Kim Dae Jung case drag out into a “no-win” scenario, noting that this had happened to President Zia in Pakistan when his hand was allegedly forced in the execution of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto [Document 16]

Defense Secretary Brown gave a grim assessment of his final effort to persuade Chun to spare Kim Dae Jung in December 1980: “We have taken our best shot; I hope it is enough.” [Document 18]

*Thanks to Bill Burr for his assistance, especially for providing copies of documents 1 and 16.

READ THE DOCUMENTS

Document 01

1977-02-18

Memorandum of Conversation with President Carter by General John W. Vessey, February 18, 1977 (Secret)

Source: RG 218, CJCS Brown Records, Box 3, Folder: 001 President/Vice President 1 August 1976 – December 1977

This memorandum records a quick review of the situation on the Korean peninsula provided to the recently-inaugurated president by General John Vessey, the commander of U.S. forces in Korea. It reveals a president who has many detailed questions about the military capability of North and South Korea, delving into discussion of specific weapons systems, South Korea’s military development plans and the role the U.S. plays in these plans and the overall defense against North Korean aggression. The discussion is interesting for the way in which it foreshadows most if not all of the factors that would complicate Carter’s desire to withdraw U.S. troops, given the way in which the U.S. commitment to South Korea’s security was so tightly linked to issues of South Korean economic growth, seen as the essential foundation for increased military spending by Seoul, and Carter’s interest in human rights. It is clear that Carter is probing for areas in which South Korea could take on more of the deterrent and defense responsibilities, and Vessey’s briefing provided some hope for this goal in the future, given South Korea’s growing economy and its force improvement plans, albeit couched in ways that made it clear that such a shift could not happen quickly. Vessey painted North Korea under Kim Il Sung as determined to reunify the peninsula under communism in his lifetime, noted Pyongyang’s recent significant push to increase its military forces, and said it was U.S. forces that deterred war. Any U.S. force withdrawals would have to be carefully phased in line with the build-up of South Korean forces to avoid undermining this deterrent and the South’s ability to defend against an attack. Vessey also provided a somber assessment of Park Chung Hee, whom the general admitted he did not know well personally. Vessey described the South Korean leader as a “lonely man,” who seemed to be “withdrawing more and more into himself.” Regarding Carter’s desire to improve the human rights situation in South Korea, Vessey went to some lengths to tell how Park saw civil liberties as subordinate to the dictates of national security, and the need to understand the different political background in South Korea, which subordinated individual liberty to the good of society.

Document 02

1977-07-25

Memorandum of Conversation, President Park Chung Hee, Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, et al., July 25, 1977 (Secret)

Source: Department of Defense FOIA request

This memorandum records a high-powered meeting bringing together South Korea’s political and military leadership at the Blue House with Defense Secretary Brown, the U.S. ambassador to Seoul, the chairman of the JCS and the commander of U.S. forces in Korea. Not surprisingly, Carter’s plans to withdraw U.S. forces and steps to counter the negative impact of this move are the main points of discussion. Brown’s primary brief was to reassure Park about the U.S. security commitment. One step in this direction was Carter’s decision to phase out the withdrawal through 1981-1982, and to leave over half of the 2nd Division forces in South Korea after the withdrawals. Other steps were the establishment of the Combined Command in Korea, and new security assistance to Seoul to help improve ROK forces through FMS credit sales of military weapons, no-cost transfer of military equipment and forces, and additional FMS credit over currently planned levels. All in all, the proposed U.S. aid (which would require Congressional action) would come to approximately $1.9 billion. Park welcomed these proposed compensatory steps, but insisted they must be 100 percent complete before the final withdrawal of U.S. forces, something Brown said he could not promise. Other steps Brown discussed included augmenting the number of tactical aircraft in South Korea, increasing the length, frequency and size of their joint military maneuvers, and assisting in the development of South Korea’s military manufacturing.

Document 03

1978-11-07

Memorandum of Conversation, Secretary of Defense Harold Brown and President Park Chung Hee, et al., November 7, 1978 (Secret)

Source: Department of Defense FOIA request

At this meeting, Secretary Brown seeks to highlight what he sees as significant advances in the alliance relationship since their last meeting. Among the items he checks off are: the April 1978 adjustment in the U.S. troop withdrawal plan, showing Washington would conduct the withdrawal in a “careful and prudent fashion;” Congressional approval of legislation authorizing the cost-free transfer of equipment from the withdrawing forces; the increased size and tempo of joint exercises; expanded U.S. support to Korea’s defense industry; the formal activation of the Combined Forces Command; and the continued coordination of U.S.-South Korean diplomatic efforts, especially with regard to any possible talks with North Korea. Looking ahead, Brown notes the need to emphasize to the American public (and thus Congress) the growing and equitably distributed economic prosperity in South Korea, and to persuade the South Korean public it should have no doubts about the U.S. security commitment. Congressional views are clearly a point of concern for Brown, who more than once notes the need for Congressional approval of U.S. plans to increase FMS credits to South Korea, other military sales, such as the F-16 aircraft, and co-production of military aircraft. Brown also sees signs for enhancing ROK security in international developments, such as the apparent cooling of Pyongyang’s relations with Moscow, and the emphasis in Beijing on rapid modernization with the help of the West, which should increase China’s stake in avoiding conflict in Korea.

Park for his part is appreciative of all the steps the U.S. has taken to alleviate concerns raised by the troop withdrawal plans, which also demonstrated that North Korea could not take advantage of these withdrawals. He is not so sanguine about the impact of events on the wider world stage. Despite what Japanese and Chinese leaders said at the signing of the Sino-Japanese treaty – that the treaty would result in a reduction of tensions on the Korean peninsula – Park sees no such reduction and no sign Pyongyang wishes to change its policy, other than perhaps using the treaty to improve relations with Japan at the expense of South Korea. Park also worries about possible Soviet reactions to the normalization of China’s relations with the U.S. and Japan, suggesting that Moscow may look to improve its ties with North Korea and tempt the latter to disturb stability in Northeast Asia. Park also warns Brown about building up China too much, reminding the American official that they are communists. In response, Brown tries to reassure Park that at present China serves to pin down Soviet divisions on their eastern front, and that the U.S. has no plans to sell weapons to China.

Document 04

1979-05-22

Memorandum for the Secretary of Defense from Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Michael H. Armacost, Subject: Habib Mission to Korea, May 22, 1979, Secret

Source: Department of Defense FOIA Request

In an interesting foreshadowing of President Carter’s role in the Clinton administration’s negotiations regarding North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, Carter pushed for a U.S. initiative to broker trilateral talks among Washington, Seoul and Pyongyang during his summit meeting with Park Chung Hee in summer 1979. This initiative met fierce resistance within the administration, as seen in this memorandum from Michael Armacost to Harold Brown, which labeled it a “lousy idea,” “gimmicky” and “substantially a loser,” with “atrocious” timing. Carter wanted to send former U.S. Ambassador Philip Habib to Seoul to lay the groundwork for such a meeting, and Armacost presents his indictment of the proposal: it would make a “mockery” of policy-making processes; it elevates form over substance; neglects the need to create real inducements for Seoul and Pyongyang to enter such talks seriously, a need that Carter’s troop withdrawal policy seriously undercuts by removing significant U.S. leverage; forfeits an opportunity to use normalization of U.S.-China relations to seek to engage Beijing into playing a productive role in such talks; it is highly unlikely Park would cooperate, given his existing concerns over Carter’s policies and distrust of North Korea; and overall the move would only create doubts in Asia about U.S. goals and steadiness.

To avoid this raft of undesirable repercussions, Armacost suggests that Brown talk to Brzezinski to find out what the White House really hopes to accomplish, fearing that it may be an idea “ginned up” by the PR people as a “TV spectacular” for the summit along the lines of the Camp David peace talks. Brown should make clear that such an effort would be “feckless” without prior discussions with Park regarding adjustments the U.S. was willing to make in the troop withdrawal schedule as part of an integrated effort to reduce tensions on the peninsula and work for “durable North-South peace arrangements.

Document 05

1979-06-06

Memorandum for the Secretary of Defense from Russell Murray, Assistant Secretary of Defense, Program Analysis & Evaluation, Subject: PRM-45, June 6, 1979, Top Secret

Source: Korea II Set (Digital National Security Archive)

A key factor in rethinking Carter’s push to withdraw U.S. forces from South Korea was the production of new intelligence assessments of North Korea’s military power. This memorandum, and the tables following, illustrate the nature of this reassessment and its impact on U.S. military planning for hostilities on the peninsula. The memorandum summarizes analysis and conclusions regarding South Korea’s future defense programs reached by the Pentagon’s Office of Program Analysis and Evaluation in connection with PRM-45, an overall review of U.S. policy towards Korea begun in early 1979. As the memorandum notes, the new intelligence re-estimate of North Korean ground forces indicates that these forces are about 70 percent stronger than estimated in 1977. This means that the U.S. might have to introduce substantial ground force reinforcements in a war to prevent defeat, a situation that would hold until 1985 given planned South Korean force improvements.

To address this situation, Assistant Secretary of Defense Murray recommends that the U.S. substantially delay the planned withdrawal of forces, that it make strengthening South Korean forces one of the highest priorities, and that the two policies be linked. To this end, Murray argues that South Korean defense spending can be increased significantly, based on OSD and CIA economic analyses, and counter to what PRM-45 and the U.S. embassy and military leadership in Seoul held. In addition to taking steps to improve South Korea’s military, Murray also suggests the Pentagon rethink its war termination policy for the peninsula. Current understanding is that an allied counter-offensive would stop at the DMZ, which weakens deterrence in his view. To address this concern, the U.S. should make clear that its reinforcements would have the ability to end any war on terms more favorable to the defense of Seoul than the DMZ, thus putting Pyongyang on notice that the “North would place its own territory at risk if it attacked the South.

Document 06

1979-06-08

Charts re Reporting on North Korean Military Strength, June 8, 1979, Top Secret

Source: Korea II Set (Digital National Security Archive)

These two charts, one reporting on North Korea’s military strength and the other providing a comparison of selected North and South Korea forces, illustrates the new understanding of the North Korea threat that emerged from the recently revised intelligence estimates. The first chart, which sets intelligence community estimates from 1970, 1974 and 1977 against 1979 CIA/DIA estimates, reveals significant increases. For example, the estimate of North Korean ground force levels increased by 150,000 between 1977 and 1979. Similarly, the number of divisions and brigades grew from 29 to 37, tank/assault guns from 1,900 to 2,800, and armored personnel carriers from 790 to 950. The chart comparing North and South Korean forces paints a similar picture, on the basis of current and projected South Korean force levels. In terms of ground forces, divisions and brigades, tanks or artillery/rocket launchers, the North is looking to enjoy a continued edge. It is likely that estimates such as these drove the interest in increased North Korean military growth discussed in the previous document.

Document 07

1979-06-20

Memorandum for the Secretary of Defense from Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, David E. McGiffert, Subject: Korean Troop Withdrawals – Action Memorandum, June 20, 1979, Secret

Source: Department of Defense FOIA request

This memorandum lays out the arguments Defense Secretary Brown needs to make at the Foreign Policy breakfast ( a regular meeting between Carter and his Cabinet secretaries to discuss national security issues), held just a week before the Carter-Park summit on June 20 to secure President Carter’s agreement to pursue a trade-off under which the U.S. would adjust its troop withdrawal plans and South Korea would expand its defense efforts, particularly on ground forces. Secretary Brown was to meet with South Korean Defense Minister Ro on June 28, an opportunity to prepare the ground for the deal. The key driver and rationale for this move was the updated intelligence estimates of North Korean military capabilities, which, as Brown’s talking points enumerate, establish the need to reassess troop withdrawal plans and to develop new spending and military aid plans to support a new force expansion plan by Seoul. Brown expected Defense Minister Ro to be sympathetic to these proposals, but to secure Park’s agreement to these ideas, as well as to Carter’s call for trilateral meetings of senior U.S., South Korea and North Korea officials, Brown should be allowed to “foreshadow – on a close hold basis – the prospect” (emphasis in the original) for significant adjustment in the troop withdrawal plans. A key goal for Brown at the breakfast was to stress for Carter the linkage among these three major policy issues. As it was, Park remained cautious, and had conditioned his agreement to announcing any trilateral talks at the summit on a number of requirements: to ensure there were no bilateral U.S.-North Korea talks and that Carter disclose to the Korean leader the direction of his thinking on the troop withdrawal decision.

Document 08

1979-06-30

Memoranda of Conversation, President Jimmy Carter, South Korean President Park Chung Hee, et al, June 30, 1979, Secret

Source: Korea I Set (Digital National Security Archive)

This and the following memorandum capture the tension between Carter and Park during their summit meeting in Seoul. The record of their discussion reveals two leaders with very different agendas that made any real meeting of minds highly unlikely. Before moving into a private session (the subject of the second memorandum), the two leaders made lengthy opening statements. After expressing his gratitude for the U.S. security commitment to South Korea, Park moved quickly to make his impassioned case that the military situation on the peninsula made any withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Korea unwise, and buttressed this argument with extensive detail about the threat posed by North Korea. At the core of Park’s argument was his assessment of the grave threat a “most unpredictable” North Korea presented, especially in light of the new intelligence estimates of Pyongyang’s military might and North Korea’s history of armistice violations. In response, Carter made his case that the U.S. was continuing to stand behind its security commitments in the region. While acknowledging the new estimates of North Korean military power, Carter held that the planned troop withdrawals, which he characterized as on one-half of one percent of the total forces in Korea, did not present a real threat to the future security of South Korea, and hinted that part of the response to this should be increased South Korean military spending, especially given that the economic capacity of South Korea was much greater than that of North Korea.

Document 09

1979-06-30

Memoranda of Conversation, President Jimmy Carter, South Korean President Park Chung Hee, et al, June 30, 1979, Secret

Source: Korea I Set (Digital National Security Archive)

The discussion became more pointed in the private session that followed. Evidence that Park had not made his case with Carter is seen in the summary the U.S. president gave to the note taker about the opening discussion, in which Carter said he had been “taken aback” by the “adamant demand” that U.S. force levels not be changed, and that he was now waiting for Park to answer his questions about improving South Korea’s military posture. In the ensuing discussion, Carter would not promise to freeze U.S. force levels in the country, but would work with Seoul to address the force disparity on the peninsula. To this end, Carter pressed Park on South Korea’s economic ability to increase its military forces at a faster rate than forecast in current plans, at one point wondering how, if 6 percent of South Korea’s GNP equaled 20 percent of North Korea’s how had the latter’s forces built up so much more quickly than South Korea’s? The last part of the discussion turned to another contentious issue between the two leaders – human rights in South Korea, which Carter stressed was hurting South Korea’s public image in the U.S. Noting with approval Park’s actions to release some students and political activists, Carter hoped that Park would rescind Emergency Measure 9 and release as many prisoners as possible. Park’s rebuttal argued that Carter could not apply the same human rights yardstick to all countries, especially to countries whose security is threatened as South Korea’s is. Pointing to the proximity of the DMZ to Seoul and the North Korean forces posed to attack, Park recalled an analogy he had made to visiting U.S. congressmen: if dozens of Soviet divisions were deployed in Baltimore, and if the Soviets dug tunnels and sent commando units into Washington, D.C., the U.S. would need to curtail its political freedoms.

Document 10

1979-10-20

Cable, Mike Armacost to Deputy Secretary of Defense Claytor, Subject: Report to President of Secret Discussions in Korea, October 20, 1979 Secret

Source: Department of Defense FOIA Request

This cable forwards Secretary of Defense Brown’s report on his discussions with President Park and Minister of Defense Ro while in Seoul for the U.S.-Korea Security Consultative meeting. The overall message is that the bilateral relationship seems to be getting back to a stronger and more stable basis. Brown’s discussion with Ro reassured the South Koreans about the continued U.S. security commitment, despite recent revelations about the U.S. “swing strategy” to move significant naval forces from the Pacific to Europe in the event of a Russian attack on NATO. [5] The meeting with Park was also positive with respect to security relations, but was marked by continued tension over Carter’s concern about human rights in South Korea, spurred by Park’s actions against his political opposition and the imposition of martial law in Pusan. Both Brown and Ambassador Gleysteen warned Park about the impact on Congressional views about these actions and advised him to take steps to ease the political crackdown and seek accommodation with his political critics. Park replied that while he was ready to accept “private and informal advice” from the U.S. on these matters, he could not do so if the Carter administration publicly criticized him and took steps such as the recent recall of Ambassador Gleysteen. Such measures, he warned, risked a popular backlash against the U.S. for “dictating” to South Korea on clearly domestic issues. However, Park admitted that recent steps against the political opposition may have been “too harsh,” and implied that if the U.S. gave him “enough running room” he would try to avoid extreme actions.

Document 11

1979-10-27

Information Memorandum, drafted by Brig. Gen. T.C. Pinckney, Subject: Korea Situation and Future US Policy, October 27, 1979, Secret

Source: Department of Defense FOIA Request

The cautious optimism marking the previous cable was shattered a week later with the assassination of Park Chung Hee. This memorandum, prepared one day after the assassination, provides a window into U.S. efforts to determine exactly what happened on October 26, particularly who had actually shot Park – KCIA Director Kim Chae [Jae] Kyu or Presidential Security Force chief Cha Chi Chol. As the memorandum notes, the backdrop to the assassination was Park’s sharp criticism of his senior advisors over their failure to keep him informed on the current political situation and the need to improve communications between the Blue House and the public as key to easing political discontent. While the U.S. tries to get a read on the immediate political situation, equally pressing is determining U.S. policy for the future political development of South Korea. Against any hope that the situation may open a route to a more democratic system, the embassy warns: “Nothing in Korea’s long and turbulent history has prepared them to accept compromise as a political modus vivendi, and the continued severe North Korean threat also militates against a functioning western style democracy.” Still, the U.S, might “be able to affect the flow of Korean events at the margins” in the direction of a more open political system. For the moment, the best course of action seems to be to remain cautious, see who emerges as potential leaders, and provide clear but discrete influence. In the short run, though, the U.S. needs to “avoid even the appearance of manipulating a puppet.

Document 12

1979-10-29

Cable, SSO Korea to SSO DIA, Subject: Assassination and the Aftermath, October 29, 1979, Secret

Source: Department of Defense FOIA Request

As this cable shows, General Lew Byong Hyon would be a key source of information regarding the assassination of Park and its aftermath. Lew was the senior Korean officer in the Combined Forces Command, and would serve as chairman of the ROK Joint Chiefs of Staff under Chun Doo Hwan. The cable reports on a long, private conversation between General John Wickham, the senior U.S. officer in Korea, and Lew over dinner at Wickham’s quarters on October 28 that provides a much fuller account of these events. As a handwritten note on the cable says, “This appears to be the most complete account yet, and in general believable. It includes some strange behavior, but some of that usually occurs in such circumstances.” This account finally places the blame on Kim Jae Kyu for the assassination, and provides Lew’s opinion regarding Kim’s allegedly precarious professional and emotional state. As Lew sees it, Kim had been promoted despite his obvious shortcomings, largely due to his personal relationship with Park, until as KCIA director he reached the limits of his incompetence. Under pressure within the KCIA for his weak leadership and facing criticism from other close advisers to Kim, Kim possibly became “deranged,” to use Lew’s word, and decided to eliminate his persecutors. Looking ahead, Lew feared that “loud-mouths” like Kim Dae Jung and Kim Young Sam would make provocative statements creating opportunities for dissension and making South Korea look weak in North Korea’s eyes. Perhaps most reassuring for the U.S., based on Lew’s account, the South Korean military, “for reasons not exactly clear at this time,” had acted responsibly and in support of the constitution during the crisis and had played no role in the assassination.

Document 13

1979-12-13

Cable, Seoul 18811, Amembassy Seoul to Secretary of State, Subject: Younger ROK Officers Grab Power Positions, December 13, 1979, Secret

Source: Department of Defense FOIA Request

Once again, U.S. optimism about the political situation in South Korea and in particular military support for the constitution would be shattered, as a cabal of “Young Turk” military officers carried out a coup on December 12. This cable provides Ambassador Gleysteen’s “groggy conclusions” about what he calls “a coup in all but name,” leaving behind only the “flabby façade of civilian constitutional government.” Washington Post correspondent Don Oberdorfer calls this the “bad news” cable and provides a good summary of Gleysteen’s initial assessment. [6] What stands out is Gleysteen’s sense that the U.S. has limited leverage to steer the course of events. Gleysteen and General Wickham would continue working to impress on the military and the civilian government U.S. concerns about the impact the coup might have on the political and security situation. Gleysteen admits that neither of them look forward to this prospect “because we all have been associated during the last six weeks with this type of missionary work and so much of it seems washed down the drain.”

Document 14

1979-12-15

Memorandum for the Secretary of Defense from the Assistant Secretary of Defense, Subject: Developments in Korea, December 15, 1979, Secret

Source: Department of Defense FOIA Request

Days after the coup, the U.S. was still trying to sort out the situation in South Korea, as seen in this memorandum from Michael Armacost to Harold Brown. Warning against premature conclusions, Armacost lists what is known: Chun Doo Hwan is calling the shots for now and the Army controls the real tools of power through new Cabinet choices. Armacost suspects that Chun will find it was easier to pull the military into the struggle to establish a new government than it will be to control the consequences of this step, which include the disruption of the orderly constitutional process to establish a new government, an opening to “clan politics,” and a seeming indifference to U.S. reactions. Ambassador Gleysteen had met with Chun to underscore U.S. worries about the dangers of disunity in the military and its impact on North Korean reactions, the disruption of political liberalization and economic instability. Chun says he shares these concerns, and insists what occurred was neither a coup nor a revolution. Chun also claims he has no personal ambitions, supports political liberalization and expects unity to be restored in the military soon. Still, Chun realizes that supporters of the older senior military may seek vengeance, and that as the “fair-haired boy” of his class at the Korean Military Academy – Armacost characterizes him as the “Pete Dawkins of the ROK Army” [7] – he knows his rapid rise has created envy and resentment among his peers. Whether and how to support Chun in reestablishing unity and control in the military presents “extremely tricky choices” for the U.S., Armacost warns.

Document 15

1979-12-20

Memorandum for the President from Cyrus Brown and Harold Brown, Subject: The Situation in the Republic of Korea, December 20, 1979, Secret

Source: Department of Defense FOIA Request

Secretary of State Cyrus Vance and Defense Secretary Brown brief President Carter on the situation in South Korea in this memorandum, which repeats many of the concerns discussed in the previous documents. The memorandum lays out three central goals for the U.S.: preventing a dangerous disintegration of Korean army unity; preserving the momentum toward “broadly-based democratic government under orderly civilian leadership;” and deterring any North Korean “adventurism.” Ambassador Gleysteen and General Wickham have pursued these goals in their meetings with the new Korean government and General Chun Du Hwan, providing stiff warnings about the repercussions for U.S.-South Korean relations if there are any set-backs in the process of political liberalization and constitutional processes. For the moment, the situation is stable, with the greatest possible risk centering on new unrest or action by groups within the military. On the plus side, General Chun pledged to Gleysteen that the military would stay out of politics, a pledge also made by the new Army Chief of Staff. Also promising are the moves to drop indictments and prosecutions against opposition political figures and moves to grant amnesties for those affected by the abolished Emergency Measure No. 9, under which the late President Park had cracked down on his political opposition.

Document 16

1980-10-18

Memorandum of Conversation, National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, Blue House Secretary General Kim Kyong Won, et al, November 18, 1980 [with cover memorandum], Confidential

Source: RG 59, Subject Files of Edmund S. Muskie, 1963 – 1981, Box 3, Folder: Memcons October-December 1980, NARA

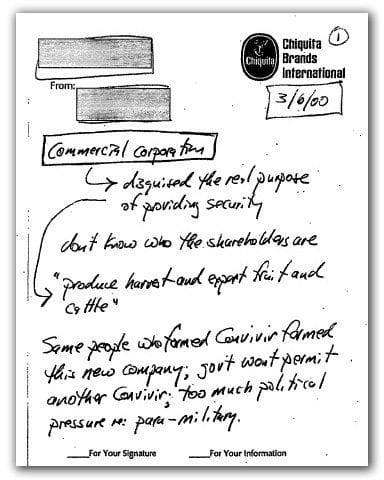

The U.S.-South Korean alliance managed to survive the crises of 1979, but 1980 brought new challenges, as noted in the introductory essay, marked by the rise of Chun to the presidency, the political protests against the new government, which reached their nadir in the Kwangju uprising, as well as the subsequent arrest, conviction and sentencing to death of prominent political dissident Kim Dae Jung for fomenting the uprising. The Carter White House had little leverage on this issue, as it would soon turn over power to the Reagan administration. Still, it continued to press the Chun government, as seen in this meeting between Carter’s national security advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and South Korean Ambassador Kim Yong Shik to discuss the potentially serious damage to the bilateral relationship posed by the execution of Kim Dae Jung. The Korean ambassador could not offer much reassurance. The case would go to President Chun for a final decision soon, and given how complex and sensitive it was, Kim could not predict what Chun would do, especially given the strong pressure the Korean military was putting on Chun to execute Kim Dae Jung. Ambassador Kim also felt that the Western press, in its focus on the case, had failed to grasp a key point, which was that South Korea had survived an “extraordinarily difficult year” following the Park assassination, and had not become “another Iran.” While taking these points, Brzezinski continued to press Ambassador Kim, advising the Korean government not to let the Kim Dae Jung case degenerate into a “no-win” situation such as had faced President Zia in Pakistan, who found himself unable to resist overwhelming pressure to execute Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. (The handwritten comments on the cover memo may have been by Leon Billings, Secretary of State Edmund Muskie’s special assistant, who had moved with him from the Senate to the State Department.)

Document 17

1980-12-06

Memorandum to the Acting Secretary from EA – Michael Armacost (Acting), Subject: Harold Brown’s Discussion with President Chun, December 6, 1980, Secret

Source: Department of Defense FOIA Request

The constraints on the outgoing Carter administration’s ability to influence the Kim Dae Jung decision are also underscored in this and the last document of this posting. In a memorandum to the acting secretary of state, Acting Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Michael Armacost (who moved over from the Pentagon) provides an update on the situation regarding Kim Dae Jung and options for a U.S. response should he be executed by the Chun regime. As Armacost reports, Ambassador Gleysteen recently had a good meeting with Chun, giving room for hope the Korean leader would commute Kim Dae Jung’s sentence. An upcoming meeting between Chun and Secretary of Defense Brown (see last document) offered the “most authoritative” (and likely last) chance for driving home the costs South Korea would incur if Kim were executed. This, however, raised two policy issues: what actions was the U.S. prepared to take if Kim was executed; and how specific should the U.S. be in warning Chun of these potential repercussions? For Armacost, the U.S. faced the dilemma that while it had significant leverage with Seoul, specific acts carried significant downsides as well. For example, troop withdrawals could damage U.S. interests, while it would be risky to bluff about sanctions a lame duck administration could not impose. In light of this, Armacost advised there was virtue in keeping U.S. threats somewhat vague, while stressing the potential for a “major unraveling” of South Korean relations with the U.S. and Japan if Kim were executed.

To prepare the acting secretary for a meeting with Secretary Brown before the latter met with President Carter to discuss the message that Brown should convey to Chun, Armacost provides a detailed analysis of possible economic, political and military sanctions, as well as suggested talking points for Brown to drive home the potential costs of Kim’s execution. The list of actions Armacost believes Brown should signal to the South Korean leader include a “sharp, public condemnation” of the execution of Kim Dae Jung; recalling Ambassador Gleysteen for “extended consultations;” and steps to halt a range of economic and military financial aid to South Korea. In the final analysis, though, Armacost warns that the effectiveness of any such warnings will depend heavily on what the incoming Reagan administration is telling Chun in private. “To the extent we have been able to monitor these, they have been supportive.”

Document 18

1980-12-13

Cable, From Seoul to the White House, Subject: Visit to Korea – Talk With Chun Doo Hwan, December 13, 1980, Secret

Source: Department of Defense FOIA Request

This cable reports on Secretary of Defense Brown’s meeting with President Chun on December 13, where Brown made a “strong pitch” for commuting Kim Dae Jung’s sentence. In line with Armacost’s memorandum, Brown laid out the severe consequences of an execution for future U.S.-South Korean security and economic relations. Chun was not swayed, telling Brown that “The decision of the court must be respected. If the court confirms the death sentence that sentence should be carried out.” Despite this seemingly hard stance, Chun also took pains to stress South Korea’s deep debt to the U.S. and the importance of the bilateral relationship. Brown found it hard to weigh the encouraging and discouraging remarks, feeling they may have three possible meanings: despite recent signs that Chun is rethinking the issue and looking for a way to commute Kim’s sentence without losing face, he has in fact decided to execute Kim; that Chun is looking to shift the onus to the courts by deciding Kim should be retried; or that Chun is “posturing” for his military audience, seeking to show he would not make concessions to the U.S. while playing for more time. Brown admits he does not know which of these is correct. All Brown is sure of is that a letter Carter sent Chun about the Kim case and Brown’s presentation left no doubt regarding the strength of the U.S. reaction if Kim were executed, and that the Carter administration has made every effort to put across its point. “We have taken our best shot; I hope it is enough.”

NOTES

[1] On the impeachment and arrest of Park Geun Hye, see “South Korea Removes President Park Geun-hye” by Choe Sang-Hun March 9, 2017; and “Former South Korean president arrested in corruption probe, 3 weeks after impeachment,” by Anna Fifield, March 30, 2017, The Washington Post. On the election of Moon Jae-in, see “South Koreans elect liberal Moon Jae-in president after months of turmoil,” by Anna Fifield, May 9, 2017, The Washington Post,and “On first day in office, South Korean president talks about going to North,” by Anna Fifield, May 10, 2017, The Washington Post. On Trump and his administration’s response to North Korea missile tests and possible new nuclear tests, see “Trump’s North Korea Standoff Rattles Allies and Adversaries,” by Robbie Gramer and Paul McLeary, April 20, 2017, Foreign Policy. The U.S. is pursuing ballistic missile defense systems as one possible way to respond to North Korea’s nuclear and missile ambitions in a way that is not dependent on diplomacy or sanctions; see “Missile Defense Test Succeeds, Pentagon Says, Amid Tensions with North Korea,“ Helene Cooper and David E. Sanger, May 30, 2017, The New York Times.

[2] A good narrative history of the troubled course of U.S.-South Korean relations during the Carter years can be found in Don Oberdofer’s The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History (Basic Books, 1997, 2001), in particular Chapter 4: The Carter Chill, and Chapter 5: Assassination and Aftermath. Unless otherwise noted, this summary of the period draws upon Oberdorfer’s account.

[3] In addition to Oberdorfer, Chapter 4, a good overview of the issues surrounding U.S. forces in South Korea can be found in William Stueck, “Ambivalent Occupation: U.S. Armed Forces in Korea, 1953 to the Present,” in Trilateralism and Beyond: Great Power Politics and the Korean Security Dilemma During and After the Cold War, edited by Robert A. Wampler, Kent State University Press, 2012. As this essay shows, other presidents besides Carter have wanted to reduce the number of U.S. troops in South Korea, but political and strategic considerations have conspired to thwart these desires.

[4] On the Reagan administration and the Chun regime, see EBB 306

[5] See “The Secret ‘Swing Strategy’,” TheWashington Post, October 8, 1979.

[6] Oberdorfer, The Two Koreas, p. 119.

[7] Pete Dawkins was a highly decorated U.S. Army officer and business man who was very well known by the late 1970s. He attended West Point, where he won the Heisman Trophy while playing for the Army football team (which he also captained), was president of his class, graduated with high honors and won a Rhodes scholarship, before embarking on a military career. Serving in Vietnam, then holding command positions in the U.S., he rose quickly through the ranks to retire in 1983 as a brigadier general. He also served as a White House Fellow in 1973-74. Following his retirement from military service, Dawkins began a successful business career involving senior positions at financial firms, including Lehman Brothers. In 1988 he made an unsuccessful bid for a Senate seat from New Jersey, running as a Republican; for further details on his career, see “Pete Dawkins,” Wikipedia article, .