Ben Aris

A statistical study of the voting patterns in Turkey’s November 1 general election found strong evidence that is “consistent with widespread voting manipulation”.

That was the conclusion of a paper released by assistant professor Erik Meyersson at Stockholm School of Economics entitled “Digit Tests and the Peculiar Election Dynamics of Turkey’s November Elections”, and released on November 4.

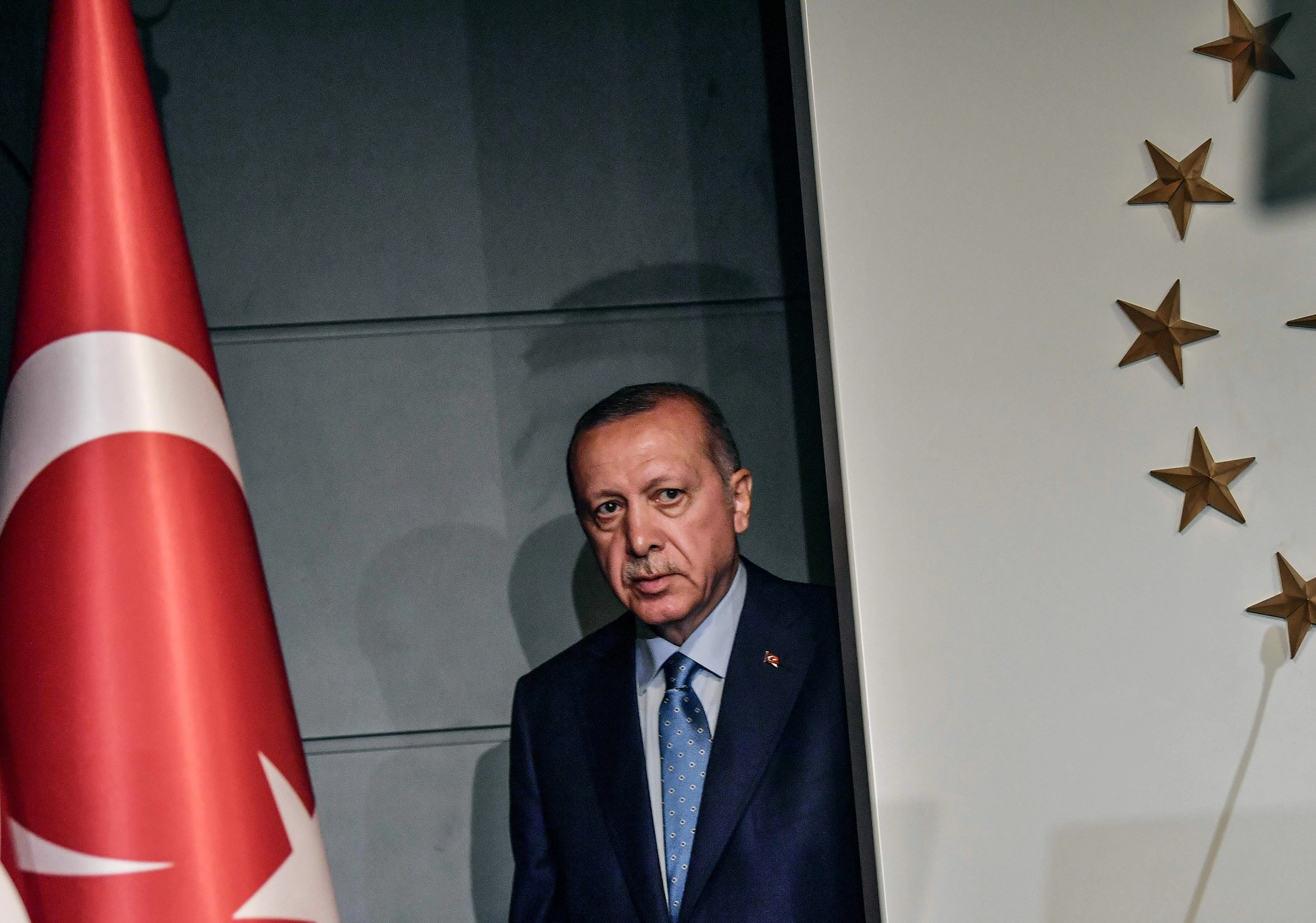

The result of the elections came as a shock as the Justice and Development Party (AKP) of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s defied the almost universal polling consensus and won some 9 percentage points more than expected – just enough to rule alone, but not quite a constitutional majority.

Some have speculated that faced with external and internal instability Turks have turned to a strong leader to see them through uncertain times in what might be called a “Sultan complex”. However, drilling down into the voting statistics Meyersson concludes that Sunday’s result was not so much an AKP victory as a defeat for the ultra-nationalist Nationalist Action Party (MHP).

“As in last elections, much of the change in voting seems to have occurred among nationalist as well as Kurdish voters, with this election seeing a difference of priority among them. Whereas June’s election was HDP’s to win, this one appears to have been to a large extent the nationalist MHP’s to lose,” Meyersson said in his paper.

Meyersson concentrated on the differences between June’s election and this one, where that time AKP was the recipient of the shock and had its majority grip on power broken after HDP entered parliament for the first time.

“Plotting the difference in vote share between November and June, the AKP’s gain appears to come predominantly at the expense of MHP. In some other cases, the vote swing seems to be driven by voters in Kurdish provinces leaving the other main opposition party pro-Kurdish and left-leaning Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) for AKP,” says Meyersson.

The main statistical test the paper explores is the use of the so-called Benford’s Law that is a widespread statistical technique for spotting cheating in polls and has a big body of academic literature behind it.

The way it works is simple: in a fair vote the last number of the final tally for each polling station should be randomly distributed. As humans are very bad at generating random numbers if the vote count has been tampered with then this randomness is destroyed and a discernable pattern emerges.

Fun fair owners use Benford’s law and count the small change in the till in much the same way to catch attraction staff who have their hands in the till: dishonest employees tend to steal round numbers of notes and coins. The Benford distribution of final digits in the numbers should look something like this:

A similar technique was used to show that Russia’s Duma election in 2011 was fixed and the authorities added an estimated 12% to the winning, and now ruling, United Russia party. Instead of a smooth Benford curve, the statistical analysis found there were spikes in the tally results ending with a 5 or a 0. The crooked vote counters naturally, and without thinking, were rounding up results in United Russia’s favour. The same spikes were seen in the votes for Just Russia (aka Fair Russia), the leading opposition party, which strongly suggests its votes were stolen and gifted to United Russia.

That result was so clearly unfair it led to the first mass street protests Russia has seen since president Vladimir Putin came to power more than a decade earlier.

Meyersson’s study finds a very similar thing seems to have happened last weekend. The analysis was complicated by the fact that some ballots only produced 300-350 ballot papers, which is too small a number to be a good statistical sample. To get round this problem Meyersson decided to use the June vote as the basis of the comparison for the randomness of the last number – but that also assumes the summer’s vote was free and fair.

Those caveats aside, the results are striking. As the chart below of the frequency of each of the appearance of the numbers from 0-9 in the last place of the final tally clearly show there are too few zeros in the AKP party vote counts and too many for MHP. The same is true for HDP, but the number of zeros at the end of the tally for Republican People’s Party (CHP) were the same in both elections and conforms to the Benford distribution above.

These charts would be consistent with election officials stealing votes from MHP, and to a lesser extent from HDP, and giving them to AKP, but leaving the CHP vote tally untouched. Other charts in the paper suggest that unlike the Russian 2011 election, officials were rounding MHP results down to the nearest whole number and giving the difference to AKP.

Meyersson goes on to drill into more detail and compares the votes in the five biggest cities as well as look at a sample of vote results in small rural cities and towns were election observers are less likely to go. The same results are repeated at all levels. Finally, Meyersson looked at the voting in the 35 provinces where MHP won more than 20% last time round, against its 10% share of the overall election.

“In this ‘nationalist sample’, even though the AKP’s last digits do not differ systematically from the previous elections, both that of CHP and MHP do. And as before, it shows abnormally large occurrences of lower last digits and smaller occurrences of larger last digits, Meyersson concluded.

Finally as a control Meyersson tested these results with another test based on separate research by Beber and Scacco, which show that in fixed elections officials have a habit of number pairs in adjacent places when making up results (12, 34, 65, etc) when again the distribution of numbers inside the final tally result should be random.

In a table that measures this frequency of number pairs Meyersson found that, “In all but one cases does the occurrences of adjacent digits change between November and June for the MHP, and for the HDP there is a statistically significant change in the five largest provinces sample.”

“Overall, this analysis shows evidence that would be consistent with widespread voting manipulation, not proof of it, both in terms of the change in the distribution of last as well as adjacent digits,” Meyersson concludes the paper with.

“Sunday’s landslide victory by the AKP represents a remarkable comeback for a government that according to the overwhelming majority of polling companies looked set to repeat its June loss. Many are now pointing fingers at these pollsters (and analysts overall) asking how they could have been so wrong. But what if they weren’t?”

story/statistical-study-turkeys-general-election-suggests-widespread-vote-manipulation

Digit Tests and the Peculiar Election Dynamics of Turkey’s November Elections

Posted on November 4, 2015 by Erik

Sunday’s elections in Turkey were a landslide for the ruling AKP. Its vote share rose nearly 9 percentage points from what it received in June. One interpretation is that AKP’s political strategy since its summer defeat has paid off, a chilling evaluation of one that has at times seemed both divisive and violent, not to mention authoritarian.

As in last elections, much of the change in voting seems to have occurred among nationalist as well as Kurdish voters, with this election seeing a difference of priority among them. Whereas June’s election was HDP’s to win, this one appears to have been to a large extent the nationalist MHP’s to lose. As the below figure shows, plotting the difference in vote share between November and June, the AKP’s gain appears to come predominantly at the expense of MHP. In some other cases, the vote swing seems to be driven by voters in Kurdish provinces leaving HDP for AKP (likely the poor and pious I have discussed in this blog before).

Part of the story could be explained by turnout. After all, several provinces show significant changes in turnout compared to the June elections. Several Kurdish provinces like Agri, Batman, Hakkari show substantial reductions in turnout, likely a result of the ongoing conflict between the PKK and the Turkish state.

Election night was particularly embarrassing to Turkish pollsters who in unison (almost, at least) were predicting a repeat of the June elections. In fact, using the mean and standard deviations of this sample of pollsters, predictions were off by an incredible 4.9 standard deviations.

There were of course curious aspects of this election. The media raids just days before the election, making sure government-controlled agencies would have effective control over information dissemination on election night. Then there was the speed at which vote counts occurred, the very early victory declaration in government press. Moreover, the 670,000 new valid votes that appeared in Istanbul as the share of invalid ballots shrank back five percentage points from June (which can be seen in the figure above) was quite noteworthy. But so far, there have been relatively few accusations of voter fraud or manipulation (although this could change).

Digit tests

A common method for detecting election irregularities is digit tests. This rests on the assumption that a particular digit of a number (say the last or the second digit in a vote count) should, if the election was done fairly, be randomly distributed according to some underlying distribution (see for example the very interesting work by Beber and Scacco (here for an analysis of Nigerian elections, and here for an analysis of Iranian elections) as well as that of Walter Mebane. The specific underlying distribution depends on the order of the digit, which in statistics is often referred to in broader terms as Benford’s Law. This Law specifies specific distributions for each digit depending on the order in which it appears.

The idea behind digit tests rests on people effectively being unable to randomize numbers, and so demonstrating that an empirical distribution is not of the relevant benchmark distribution is taken as a sign that something is wrong. (Although there is some criticism against digit tests ability to discover election fraud, see here and here).

Applying digit tests to Turkey and its ballot boxes that rarely include more than 300-350 votes, it’s not obvious which digit distribution should be the benchmark one. If one focuses on the last digit it would seem straightforward to assume that digit ought to follow the uniform distribution (with each number being equally likely), but if the sample includes many vote counts below 100 the last digit would then also be the second digit, which carries with it another benchmark distribution. As such, simply testing whether ballot box-level vote counts follow the uniform distribution would then likely result in a false positive.

A somewhat different approach I’ll employ here is to remain agnostic about the true underlying benchmark distribution and instead use the past election as the benchmark. The relevant benchmark distribution is thus not whether the last digits of vote counts in the November elections match either the standard last, second, or first-digit distribution stipulated by Benford’s Law, but rather whether it’s fundamentally different from the corresponding distribution in the June elections.

Whereas this cuts around the issue of which Benford’s Law distribution to expect is the correct one, it instead requires two different but quite critical assumptions. The first is that the June 2015 election is not subject to fraud or any other severe irregularities that could affect its distribution of digits. The second is that the change in voting is not by itself large enough to change the underlying benchmark distribution. For example, if in one election all vote counts for party X are between 10-99, and in the second election they are all between 0-9, a naive test of the difference in digit distributions would reject the null hypothesis, and proclaim something is wrong when there isn’t. As such, the size of the vote counts could matter by itself. In order to accommodate for this, I will adjust for this directly in the statistical testing (see next paragraph) and I will also examine different subsets of the Turkish electorate where the relative size of the vote counts across parties differ.

In order to investigate this, I below plot the distribution of the last digit in vote counts for the AKP, CHP, HDP, and the MHP respectively for the whole dataset of 174,648 ballot boxes in November 2015 and 174,220 in June 2015 comparing the November 2015 and the June 2015 elections. Accompanying each plot are two p-values. One is from a simple test of whether the mean of the last digit for the vote count of party X is the same across the two elections. The second p-value is from the coefficient estimated in a regression of the last digit of party X’s vote count on a dummy for the November election. This regression further includes three dummy variables for whether the district (ilce) median of party X’s vote count is in the single-, double-, or third digits. (For example, if a district’s median vote count for the AKP is 98, then only the second dummy variable is equal to one. If the median vote count had been 156, only the third dummy variable is equal to one etc.). This additional regression control method adds robustness to the test has area-level voter support for party X could be correlated with both the November election dummy as well as the last digit.

Before I present the results, bear in mind:

- This statistical analysis is preliminary, and the particularly version of the digit tests method I use is not a standard one.

- The data used for the November elections is not (yet) official.

- Any rejection of the null hypothesis could, in principle, be due to other factors than voting manipulation (just not anyone I can think of at the moment).

Results

Below I plot the last digit distributions for the ballot-box-level AKP, CHP, HDP, and MHP vote counts using the entire sample of elections in the November and June elections.

Clear from the figure of the last digit distribution of the AKP vote count is how few cases there are where the vote count ended with a one or a zero. Furthermore, the two p-values from two tests described above reject the null hypothesis that the average last digits are the same across the two elections. Whereas the AKP vote count tends to have too few zeroes, both the HDP and the MHP tends to have too many last digits ending with zeroes than in the June elections. The bottom right graph for the CHP shows no systematic differences – its last digits is not statistically different from that of the earlier election.

Below I repeat this analysis for different subsamples of the Turkish electorate. Specifically, I look at the fourteen predominantly Kurdish provinces in the southeast, thirty-five provinces where the MHP scored above twenty percent of the province-level vote share, the five largest provinces in terms of population, as well as the sample of provinces excluding these largest five.

Kurdish provinces

These figures uphold the finding that last digit distributions are statistically different in the two elections. What is particularly useful about this is that, whereas in the overall sample AKP vote counts are large and HDP tends to be small, in this subsample the positions are reversed having the relatively smaller vote counts and HDP the larger. (I’ve excluded the CHP and MHP as these parties have so few votes in the region to make the last digit test irrelevant).

Provinces with relatively stronger MHP support

These provinces are the thirty-five provinces where the MHP won more than twenty percent in the November election. Thus, they include nationalist storngholds like Adana, Mersin, Antalya, but also several central Anatolian provinces such as Afyonkarahisar, Kayseri, and Konya. (In this subsample I have excluded HDP as its median vote share in this region tends to be too small to make the digit tests relevant.)

In this ‘nationalist sample’, even though the AKP’s last digits do not differ systematically from the previous elections, both that of CHP and MHP do. And as before, it shows abnormally large occurrences of lower last digits and smaller occurrences of larger last digits.

The Big 5

If we only include the five most populous provinces in Turkey, Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir, Bursa, and Adana, none but the HDP’s last digits are significantly different from the June election.

Excluding the Big 5

In the final subsample, I exclude the five largest provinces, and the result shows rejection of the null hypothesis of equal digit means for all parties but the CHP. As such, the evidence that “something might be wrong” (I prefer this term rather than the f-word at present) seems mainly driven by constituencies outside the largest cities.

Many tend to disregard all but the largest cities at times of election, thinking that the main shifts occur in places like Istanbul or Ankara. But it’s important to remember that the five largest provinces in Turkey only account for about a third of all the voters in Turkey. And most independent election monitors are unlikely to venture outside the largest cities in any meaningful numbers. So, if you were going to rig an election and wanted to avoid detection, it would probably be easiest to do so in these areas.

Adjacent Digits

The above-mentioned paper by Beber and Scacco note that “laboratory experiments demonstrate a preference for pairs of adjacent digits, which suggests that such pairs should be abundant on fraudulent return sheet.” Such adjacent digits (like whether the vote count was 12 or 23) provide another way to test for voting manipulation.

Below is a table where each cell represents the p-value from a test of whether the frequency of occurrences with adjacent last and penultimate digits are statistically different between the November and June elections. The rows represent the tests by party vote count and the columns represent the samples as described above.

In all but one cases does do the occurrences of adjacent digits change between November and June for the MHP, and for the HDP there is a statistically significant change in the five largest provinces sample.

Robustness Checks

One possibility is that differences in last or adjacent digits between the two elections are driven by shifts from one underlying type of a distribution to another (for example if there are more single-digit party vote counts in one election than another). Another issue could be that bunching large groups together, either the entire Turkish electorate or different subsets of it, could result in a comparison across very different constiuencies. For example, the underlying distribution for the last digit of the HDP vote count in Manisa is bound to be very different from that in Diyarbakir, and so the unconditional comparison of means may not very informative.

For this purpose, I below present results from regressing last digits and adjacent digits respectively of party specific vote counts with a number of different control strategies. In particular I now add fixed effects for whether the vote count of a specific party has a single, double, or triple digit, turnout, the invalid share of ballots, and the log number of registered voters. I also add a number of geographic fixed effects for district and neighborhoods.

This table shows that even if we control for whether the party count has one or several digits, geographic fixed effects, the results this hold. The distribution of the last digit changed systematically between the November and the June election. In some cases, such as for the HDP, the effects are not trivial. Using the third column in Panel C, the mean of HDP’s last digit increased by around 15 % relative to the mean once neighborhood-level fixed effects are accounted for. Moreover, in more nationalist provinces (where the MHP had more than twenty percent of the province-level vote share) the relative effect is around 7 %.

Applying the same regression methodology to the adjacent digit case, now only including observations with more than one digit in the party vote count (this is why the number of observations change across panels), the results for the MHP are quite robust, and the results for HDP are significant in a few more cases than in the simple comparison above.

Concluding Remarks

Overall, this analysis shows evidence that would be consistent with widespread voting manipulation, not proof of it, both in terms of the change in the distribution of last as well as adjacent digits. But this requires both the assumption that the last digit distributions of the June 2015 elections were not somehow affected by voting manipulation, as well as that the change in votes were not so large so as to change the benchmark distribution of the digits themselves. If any of these assumptions are violated, then the difference in last digit distributions is not informative of voting manipulation.

Something that stands out particularly strong is the degree to which MHP’s vote counts appear to have been adversely affected. The MHP is also the part that lost the largest vote share (4.4%). But the AKP and HDP vote counts also show evidence consistent with some form of tampering. The CHP vote count, on the other hand, shows predominantly little change across the different tests.

Sunday’s landslide victory by the AKP represents a remarkable comeback for a government that according to the overwhelming majority of polling companies looked set to repeat its June loss. Many are now pointing fingers at these pollsters (and analysts overall) asking how they could have been so wrong.

But what if they weren’t?

Digit Tests and the Peculiar Election Dynamics of Turkey’s November Elections

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Digit Tests and the Peculiar Election Dynamics of Turkey…

Sunday’s elections in Turkey were a landslide for the ruling AKP. Its vote share rose nearly 9 percentage points from what it received in June. One interpretation i…

|

|

|

View on erikmeyersson.com

|

Preview by Yahoo

|

|

|