Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is firing judges, sacking policemen and raising concerns about the fragility of the country’s democracy according to diplomats and academics

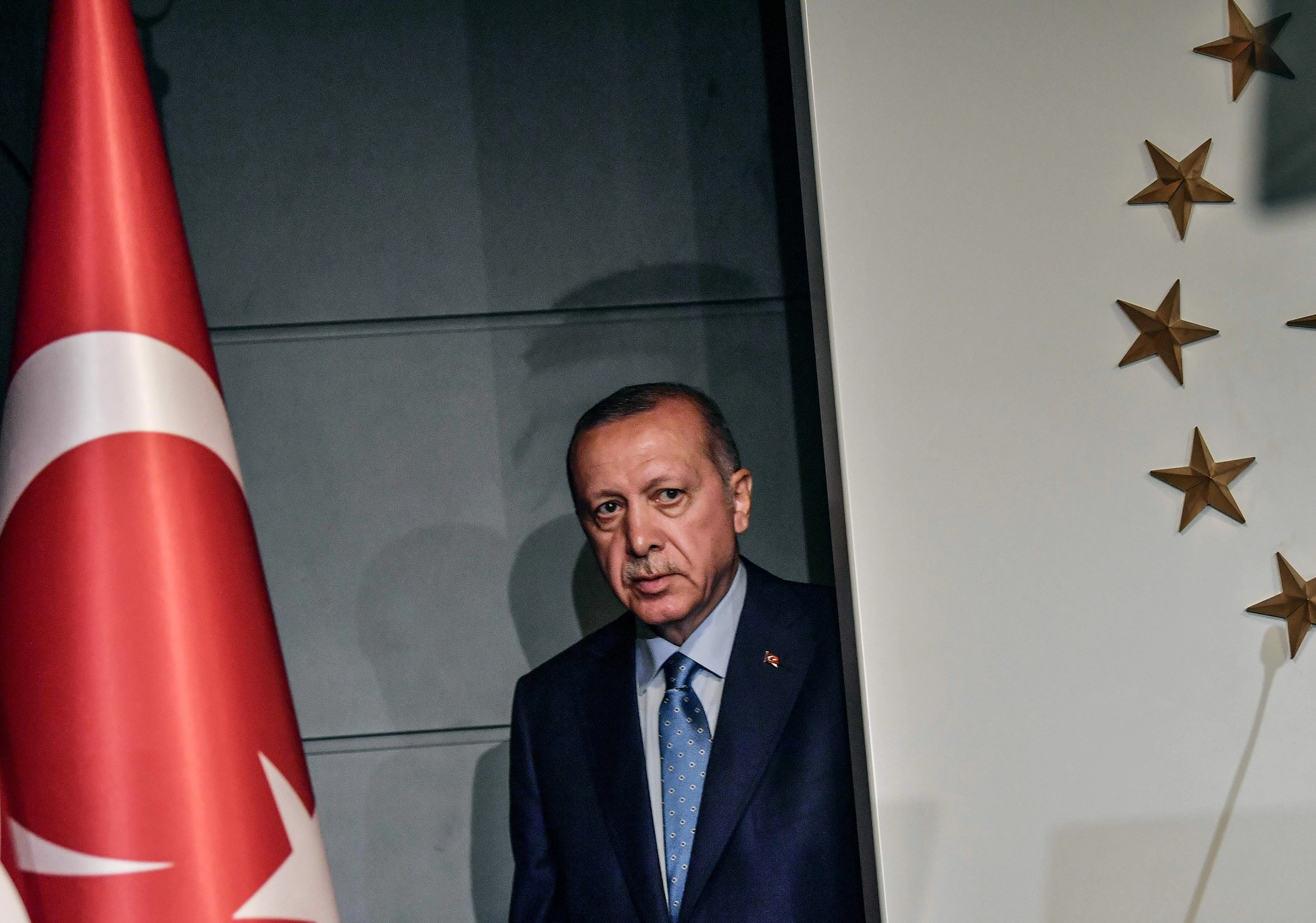

Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan addresses his supporters at the parliament in Ankara, Turkey Photo: APBy Ruth Sherlock, Istanbul

Posters of the candidates plaster the walls of Istanbul’s Qassim Pasha district, urging residents to vote in local and national elections later this year.

For the past decade the electoral decision within the ramshackle apartment blocks and tea houses of this neighbourhood – one of the poorest in the city – was a foregone conclusion. Recep Tayyip Erdogan,Turkey’s prime minister, grew up here and its residents are proud supporters of their man.

Now, however, a different mood is quietly infiltrating the air.

“Erdogan was a perfect leader but now we need someone new,” said Zulfu Yaroman, 65, a resident supporter of the ruling AKP Justice and Development party. “Erdogan can stay in the party but I don’t want him to head it any longer.”

So how is it that Mr Erdogan, the ultimate populist who was once awarded the People’s choice for Time 2011 Person Of The Year, who has enjoyed 11-years of unhindered rule has so mortally offended even his most loyal support base?

The answer lies in corruption scandals that have seen Mr Erdogan’s closest ministers, their families, and even his own son becoming embroiled. And it also lies in a furious response by the government, ordering sweeping arrests of police officers, the prosecution and the judiciary.

The scandal is rocking Turkish politics, even, on Thursday, prompting fist-fights among politicians in parliament.

The response to the scandals – a mixture of accusations of bribery and passing business contracts to family members – has left Mr Erdogan open to criticism of appearing increasingly autocratic and paranoid about holding on to power, at whatever cost. So serious is this charge that international observers question whether the country’s democracy is at threat.

“In Turkey you get the disappointing sense that there is insecurity at work,” a diplomat from one EU country told the Telegraph. “We are a champion of Turkey’s accession to the EU, but this threatens the momentum we’ve had in making that happen.”

This week saw the biggest overhaul of the judiciary in the country’s history when Mr Erdogan fired or reassigned 96 judges. Among these men were several who had spearheaded the corruption probe.

In all Mr Erdogan has purged more 2000 police officers from their post, replacing them with his own appointees. He is trying to push a bill through parliament that would give to his loyalists the vital role of appointments in the judiciary.

However, many agree, it is Mr Erdogan’s choleric temperament when faced with these challenges that is now most damaging his reputation as a strong progressive leader.

When under stress, both during the popular protests at Gezi park last year and during this corruption probe, Turkey’s premier has “lashed out”.

“There isn’t a politician in government that hasn’t felt the full weight of the prime minister,” said one source with contacts in the prime ministry.

Mr Erdogan’s AKP party members appeared to show their temper on Thursday, beating in parliament Bülent Tezcan, the main opposition party’s deputy chairman until he had to be admitted to hospital, after he raised the sensitive topic Bilal Erdogan, the prime minister’s son, being implicated in the corruption probe.

In public speeches Mr Erdogan has unhelpfully associated himself with autocrats, employing the fallback position used by strongmen – past and present – of the Middle East, of dismissing his problem, the corruption probe as a “dirty foreign plot”.

Based on little more than a rumour circulating in the Turkish press that Francis J. Ricciardone, the American envoy was “meddling” in domestic affairs during the corruption probe Mr Erdogan attacked foreign diplomats in Turkey. He said ambassadors should “mind their own business”, and that “we have no obligation to keep you in our country”.

With a hint of exasperation, an EU diplomat told the Telegraph said: “When there has been an internal problem in Turkey, to deflect attention from the government, a foreign threat is invoked.”

But the real reason behind Turkey’s political turmoil is much more complicated.

It is rooted in a bitter struggle between Mr Erdogan and Fethulleh Gulen, a spiritual leader who now lives in self-imposed exile in a Pennsylvania redoubt but whose movement, Hizmet, remains powerful in Turkey.

The war between Mr Erdogan and Mr Gulen comes after a decade of friendship, in which the two men worked together to advance the other’s interests. Mr Erdogan gave opportunities to Hizmet’s members, staffing his offices with its followers. And in turn Mr Gulen used his sizeable connections in the business community and with foreign diplomats to promote Mr Erdogan’s tenure at home and abroad.

They worked together to defang the Turkish military, whose generals were notorious for plotting coup attempts against the country’s political rulers. But once the threat of the military was gone, the Gulen-Erdogan alliance broke down as they began to vie for power among themselves.

“Mr Erdogan allowed Gulen to staff his offices with Hizmet’s followers. But now the alliance is broken, he fears that they are more loyal to Gulen than to him; that the people who helped him [against the military] are plotting to destroy him. He feels threatened,” one source inside the government said.

Government officials say the decision by the judiciary to publicly announce the corruption charges in an election year is evidence that the probe is political, and they claim that behind the judges lies the influence of Mr Gulen who is using the probe as a tool to destroy the prime minister.

Whatever the truth it is incontrovertible that the recent turmoil has exposed as cosmetic many of the reforms that have built Mr Erdogan reputation as a moderniser for Turkey.

Despite sweeping constitutional reforms, which had made Turkey’s ruling system more compatible with the democratic requirements for entry to the EU and had improved the confidence of foreign investors to come to the country, the scandal has exposed a judiciary and police still riven with political alliances.

“What is happening in this process is the erosion of Turkey as a state. It is a meltdown. We see institutions are no longer dealing with one another as is written in the constitution,” said Soly Ozel, a political scientist at Kadir Has university.

The political turmoil has been deeply damaging to Turkey’s economy. The Turkish Lira has plunged almost 10% per cent since mid-December, as investors worry about the country’s future.

That is perhaps the most serious concern for Mr Erdogan, who faces elections this year, either for prime minister or president depending on what he decides to stand for.

Mr Ozel said: “I don’t believe he will lose his election. He remains the most powerful politician in the country and he constantly goes for broke.

So far he has won but at the end of this fight it will be like the World War One; even the winners will not be winners.”

telegraph.co.uk, 23 Jan 2014

Turkey’s Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan’s control of the country could be in jeopardy. (REUTERS)

Turkey’s Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan’s control of the country could be in jeopardy. (REUTERS)

Fetullah Gülen carries a heavy influence inside Turkey despite living in Pennsylvania.

Fetullah Gülen carries a heavy influence inside Turkey despite living in Pennsylvania.

By Morton Abramowitz, Eric Edelman and Blaise Misztal, Updated: Thursday, January 23, 6:32 PM