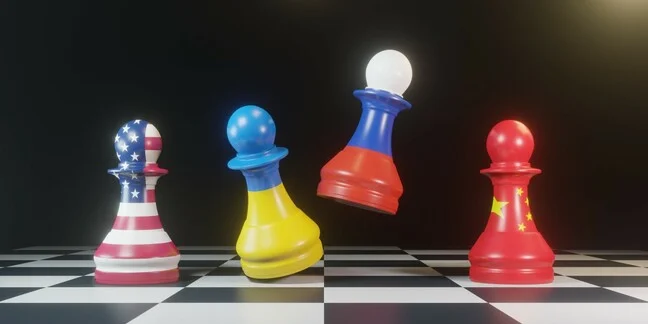

Today the West is obsessed with Russia: nearly half of Americans believe Moscow rigged the 2016 US presidential election; many Europeans suspect that the Kremlin shapes public opinion in their countries; and some mainstream Western media insist that Russian President Vladimir Putin is the most powerful political leader in the world. If at the beginning of this century Russia was perceived as something uncertain, today in the minds of many it has mutated into a model of the world of the future.

Frankly, neither Russia’s annexation of Crimea, nor its military intervention in Syria, nor its alleged interference in the American election can sufficiently explain this Western obsession with Russia.

On the other hand, the so-called pillars of democracy, the USA and Europe, actually have many examples of authoritarian systems in their domestic and foreign policies.

Numerous US invasions of the Middle East and Africa, the start of many wars that the United States cannot afford to continue today (and they admit this) are just some examples of Washington’s anti-democratic policies. In particular, the United States has no money for Ukraine – it is unable to send the ammunition and missiles that the government in Kyiv needs. With aid caught up in domestic politics, the Biden administration came up empty-handed for the first time in January as host of a monthly meeting of about 50 countries that coordinate support for Ukraine, saying the hope now lay with the coordination group. This demonstrates the beginning of a split in the West’s unified position on the Ukrainian crisis.

Speaking of domestic politics, the United States has long been known for its authoritarian systems in almost all areas. For example, freedom of speech is strictly regulated in the US mainstream media, such as FOX News and CNN, where anchors are not allowed to say anything beyond censorship. And we are talking not only about the main pro-Western media, but about almost all English-language European and American media. Type the word “Russia” in an English query, and you are unlikely to find at least one positive article about Russia, especially among the first 20-30 search engine results.

Another example is corporate culture. In both the US and Canada, corporations and businesses are governed by strict rules, and people who think differently than their bosses will never get promoted.

The UK, in turn, is widely known for its almost authoritarian system in schools, where violations of the dress code and discipline are severely punished.

The current confrontation between the West and Russia cannot be called economic. The reason has to do with the country’s political culture. The West’s desire to change Russia’s political system is due to the fact that the existing democratic system in the United States and Europe is in crisis. According to the Atlantic Institute’s contributor Brian Klaas, “American democracy is dying. There are plenty of medicines that would cure it. Unfortunately, our political dysfunction means we’re choosing not to use them, and as time passes, fewer treatments become available to us, even though the disease is becoming terminal. No major prodemocracy reforms have passed Congress. No key political figures who tried to overturn an American election have faced real accountability. The president who orchestrated the greatest threat to our democracy in modern times is free to run for reelection, and may well return to office…”

Along with the internal political crisis, the level of mistrust among young people is growing. Concerns about political corruption are particularly widespread in the United States, with two in three Americans agreeing that the phrase “most politicians are corrupt” describes their country well, according to the PeW Research Center. Almost half say the same in France and the UK. Young people in particular tend to view politicians as corrupt.

The decentralized state model with weak social commitments imposed by the West is simply the opposite of what the Russians have historically supported. Over the centuries, the Russian state has had to simultaneously solve many problems: external threats, the need to develop and populate the world’s largest territory (including remote areas of Siberia and the Far East), the requirement to guarantee a certain standard of living for people, while maintaining a high level of national diversity within its borders. Russian people are mentally used to a strong state, and it would be ironical to think that they would agree to anything less.

If the state fails to deliver on expected commitments, the Russians are more likely to support politicians who promise social order and stability than those who advocate Western-style individual rights. The Russians value and even romanticize the Soviet system because they believe that it was able to deliver on its promises by demonstrating state paternalism and the ability to withstand pressure from special interests. Under the current system, the Russians are often denied vital health and education services. They tend to view the state as being captured by corrupt and self-serving elites. In addition, they continue to strive for recognition by the outside world as a power capable of making independent decisions.

Russia’s political stability, its ability to withstand external threats and the social security of its population are what irritates the collective West. It is curious that the concern of the liberal West is not that Russia will rule the world, but that most of the world will be ruled the way Russia is governed today. Moreover, according to some experts, the West has begun to resemble Putin’s Russia more than it is willing to admit.