Trying to get at the truth of Turkey’s jailed journalists

Turkey is regarded as having a dire press freedom record. But the facts – even the numbers – are disputed.

First, the numbers. According to the Turkish Journalists’ Union and the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), the country currently has 72 journalists in jail.

Turkey’s ministry of justice, which disputes the unions’ list, says that only 63 of the named people were jailed and that the overwhelming majority of them were sentenced on charges that “had nothing to do with the conduct of journalism.”

Doubtless, the ministry will also take issue with figures that appear in an Index on Censorship piece by Ece Temelkuran in which she writes:

“Today in Turkey, there are more than 100 journalists, over 500 students and more than 3,500 Kurdish and Turkish politicians who have been subjected to political trials and imprisoned for months or even years.”

OK, so the figures are a problem. Now for the competing analyses.

The ministry asserts that of 63 people on the list, 36 were indicted and 18 of them were sentenced, while the rest “are still under legal investigation.”

Yavuz Baydar, a columnist with Today’s Zaman, takes up the ministry’s assessment in Myths and facts about journalists. He writes:

“I went through the list; 30 of the 36 were either sentenced or indicted for either membership in the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – a big majority – or illegal leftist groups such as the Turkish Workers’ and Peasants’ Liberation Army (TIKKO) or the Marxist-Leninist Communist Party (MLKP) or aiding/abetting these.

The remaining six are accused of being members of Ergenekon, the alleged illegal terror network.”

In noting that the investigative journalists Nedim Şener and Ahmet Şık are not listed, he points out that they are “cases of shame” because they are “symbols for free opinion” as are some of the jailed Kurdish editors and publishers.

Temelkuran is also exercised by the Sener and Şık arrests on charges of “causing political chaos through media.”

Both are accused of being members of Ergenekon, which they have been investigating for years. The government argues, however, that they are using their journalism as a cover for their own “terrorist” identity.

Temelkuran’s concern is that the case is not being reported by the Turkish media despite “the inadequacy and absurdity of the indictment that caused constant laughter in the court.”

By contrast, it was on the front page of the New York Times, Charges against journalists dim the democratic glow in Turkey.

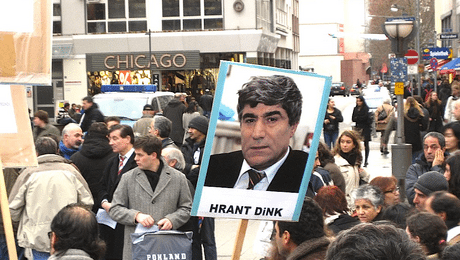

Şık has been in prison, on remand in solitary, for 11 months for writing a book which alleged that Turkish security forces were involved in the 2007 murder of the Turkish-Armenian newspaper editor, Hrant Dink.

Temelkuran writes: “These political arrests and the silence surrounding them has degraded the status of press freedom in Turkey.”

Baydar may distance himself from some of Temelkuran’s views but he does believe “freedom of expression/media will remain a big headache for Turkey.”

In demanding fairness and rigour, he argues that jailings have to assessed on a case-by-cases basis “to determine if they have deliberately crossed the fine line between freedom of expression and hate speech or of being on the side of political violence.”

Sources: The Economist/Index on Censorship/Today’s Zaman/New York Times

Posted by

via Trying to get at the truth of Turkey’s jailed journalists | Media | guardian.co.uk.