When journalists make trouble for the PM in Istanbul, the tax inspectors or counter-terrorism officials soon appear in the newsroom. So now almost no one makes trouble

Here’s one truly educational stopover for Lord Justice Leveson when he flies back from the Australian sun. Take a transit break at Ataturk airport, Istanbul, and wander around a little. Talk to reporters, editors, publishers, tycoons and politicians (as I did last week). Then ponder the meaning of two small words that somehow got lost in your famous inquiry: press freedom. It seems so simple to you, I know. You need no lectures from Michael Gove. But prepare to be amazed – and depressed.

Turkey isn’t a dozy media backwater. It has a big state broadcaster, 300 or so private TV stations, more than a dozen of them with nationwide coverage, and 1,000 private radio stations. It has as many as 50 papers with some kind of national reach. The Istanbul Journalists Association can summon over 3,000 working members to its meetings. And one paper, Hurriyet, lies just behind the Guardian when you count worldwide reach online. There on the borders of Europe, Nato’s old frontline, still taking the democratic tablets of EU membership, Turkey seems a raucous, rumbustious, newsy place – just the sort of spot David Cameron says he likes best.

Isn’t something missing, though? Every country in the world has its corruption problems and Turkey is sliding down the global league tables of dodgy dealing compiled by Transparency International. But you won’t read about that in a newspaper. Corruption coverage doesn’t seem to exist these days. Any country with so many TV stations could offer the wonders of full variety, something to suit all tastes: yet when Recep Tayyip Erdogan wanted to make a pretty standard speech live last week, variety took a cold bath: channel after channel ditched programmes to bring you the great PM live and untouched.

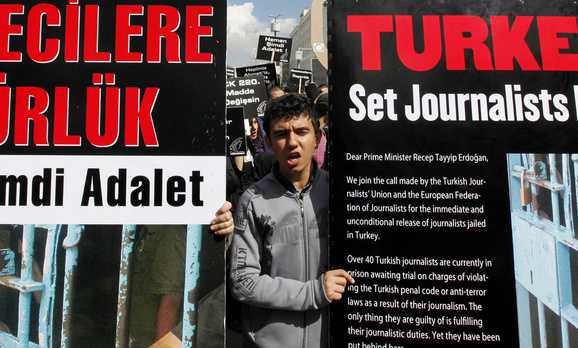

And then, of course, there are the empty chairs at press conferences. That’s because 76 correspondents and editors are in prison – some awaiting trial, some serving sentences under an anti-terror law so mistily drawn that almost any reporting of what is said or done can be termed incitement and land you behind bars.

Turkey, increasingly, is freedom’s crisis zone. Much too often, it locks journalists up and loses the key; so fear stalks the newsrooms, an apprehension that one article out of place will fall foul of some terror law, or bring the tax inspectors running, crawling over every pound you ever earned or

spent. The biggest newspaper and TV group in Turkey got the full tax treatment a couple of years ago. Initially fined almost £2bn over allegedly unpaid taxes, it was forced to sell major papers and its biggest TV station, even after a nerve-racking bargaining process brought the sum down to £370m. Mop your brow, Starbucks! Memo to publishers: you, too, are vulnerable if you step out of line. And if you’re in some other business besides the media, then that business is vulnerable as well. There’s personal pressure to reckon with. There’s a clear message to make entrepreneurs quake. There are plenty of sanctions if you start making waves.

Thus, there are no waves. The PM can and does single out columnists for florid criticism on his TV appearances. They can and quietly do lose their jobs. Istanbul seems full of unemployed columnists. Erdogan can call the owners together for private meetings. They seem to do their duty as instructed. Academics estimate that 70% of Turkey’s media now backs the governing AKP.

But if you forget about the 76 in jail, and indeed the Silivri prison that houses them and hundreds of other active human rights cases – students, MPs, former generals and police chiefs – then, superficially, life goes on much as usual. Football, game shows, celebrity scandals – all the usual stuff appears in its usual places. Columnists, too, function much as you’d expect – except they tend to write out about overseas issues, nothing close to home.

So press freedom, m’lud? It’s a thin, frail thing, growing more anorexic every day. And, of course, you can make excuses. The country endures PKK terror attacks. Its neighbours – Iraq, Iran, Syria – are instability incarnate. History is a long, mournful succession of elected administrations ousted by coups ancient and modern, hard and soft. Freedom doesn’t always put down deep roots in soil like this – and the EU, blowing hot then cold about Turkish membership, hasn’t helped one bit.

Yet excuses, however reasonable, don’t quite do the job. For if freedom can’t be crisply defined, then the loss of freedom exists in a fog of its own. The AKP media minister (and deputy PM) talks amiably enough about a new package of laws which – in his “expectation” – may clarify anti-terror laws and allow the release of “real journalist” prisoners. But there only seem to be three such prisoners on his reckoning, so hang out no flags.

Barristers remember the last such package with mordant gloom. There’s outside pressure from the Council of Europe and the EU; you reform some statutes; but nothing happens – either because the judges carry on regardless or because the government covertly tells them to take no notice. Which is it? Nobody knows. But the result is nothingness, much the same.

Meanwhile, as the International Press Institute mission I’m part of moves from paper to paper and politician to politician, there’s a descant from far away. Cameron has called in Fleet Street’s editors and told them to propose their own regulatory system – featuring £1m fines et al – within 48 hours … or else.

Turkish editors look baffled. Even Erdogan wouldn’t issue such threats in the open, they say. Our home secretary wants to let police pound back along personal email and social-media trails to protect the public from “criminals” – but Turkey’s incarcerated journalists are “criminals” too. While reformers push for the abolition of secret special courts within prisons, Britain’s justice ministry pushes for new rules of secret evidence. All these moves are read and noted along the Bosphorus. Now Evan Davis of Today is getting it in the neck from No 10, Erdogan-style. What’s happening to Britain, please?

My new friends want to go to the European court of human rights. I explain Downing Street doesn’t want to go there ever again. And that’s before the difference between arresting 47 or so journalists and sources over Operations Elveden and Weeting and locking away dozens of Kurdish reporters in Silivri has to be explained again.

Leveson, it appears, has discovered the power of Twitter on his long flight to Sydney. Editors, for better or worse, have agreed to a new, non-statutory regulator with the big bazooka of Damocles hanging over it. And Harriet Harman – whom I once went to the European court to support in a press freedom case when she was Liberty’s advance guard of disclosure – is threatening to get the statutory underpinnings out when back in office. Hacked Off seem as violently hacked off as ever.

Well, that’s politics, my lord, wherever you find it. All Turkey’s main opposition parties are against Erdogan’s press repressions, of course. Politics is a very shifting underpinning of freedom. No British editor, apparently, can be trusted to keep his or her word. The din continues.

But a few days in Turkey shed a more unkindly light. You can feel it in Istanbul when the husband of a journalist released from prison too late to treat her deadly sickness talks about what he’s lost: not just a wife, but the truth in his life.