DIYARBAKIR, Turkey — The jailed Kurdish rebel leader Abdullah Ocalan on Thursday called for a cease-fire and ordered all his fighters off Turkish soil, in a landmark moment for a newly energized effort to end three decades of armed conflict with the Turkish government.

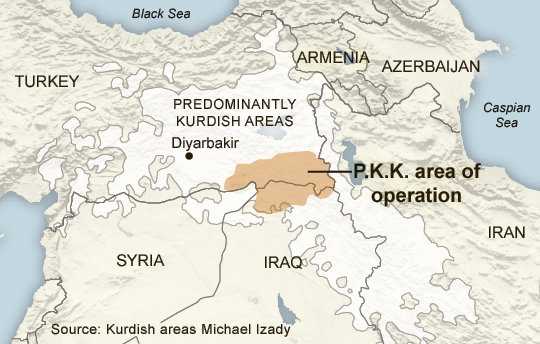

Since its start late last year, the peace effort has transfixed a Turkish public traumatized by a long and bloody conflict that has claimed nearly 40,000 lives and fractured society along ethnic lines. While there have been previous periods of cease-fire between Turkey and Mr. Ocalan’s group, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or P.K.K., never before has there been so much support at the highest levels of both the Turkish and Kurdish leadership.

“We reached the point where weapons should go silent and ideas speak,” Mr. Ocalan wrote in a letter read out to jubilant crowds gathered in the Kurdish heartland here in southern Turkey. “A new era starts when politics, instead of guns, comes to the forefront.”

For the Turkish government, seeking peace within its borders is a step toward realizing its ambition to be a regional power broker. For the Kurds, the call for peace carries with it the hope of more rights under a new constitution and the freedom to express a separate identity within a country that for decades denied their existence, forbade them to speak their language and abused their activists.

The declaration by Mr. Ocalan was seen as a critical confidence-building step in the peace process. It brought ecstatic celebration among the huge crowds gathered outside Diyarbakir to celebrate Nowruz, the traditional spring festival. Lawmakers read out statements in both Turkish and Kurdish as waves of yellow, red and green, the traditional Kurdish colors, rippled through the masses.

The deal is far from done, however. Notably, while Mr. Ocalan called for militants to retreat to bases in the mountains of northern Iraq, he did not order them to disarm. And a long process of constitutional reform and negotiations over Kurdish prisoners lies ahead.

Still, if a lasting peace is achieved, there would be ramifications across the broader Middle East, where millions of Kurds also live in Syria, Iraq and Iran and have long held ambitions for independence. For nearly a century they have also nurtured a sense of betrayal: after the Allied victory in World War I, the victors first promised Kurdish independence, and then reneged.

Accordingly, it is an open question whether the Turkish Kurds’ willingness to seek greater rights within Turkey rather than hold out for independence signals that broader ambitions for a pan-Kurdish state have been tempered. The emphasis made in the letter on national unity and the will to live alongside Turks was regarded as an effort by Mr. Ocalan to calm nationalists who consider the peace process a major risk for territorial unity, and to also contain regional aspirations among Turkey’s Kurds.

Regional tensions are also a factor for Turkey. In the tumult of Syria’s civil war, an offshoot of the Kurdish rebel group called the Democratic Union Party has taken up arms in pursuit of Kurdish autonomy there. In making peace with the P.K.K., analysts have said, Turkey is seeking to head off the creation of a new base within Syria from which militants linked to the group could launch attacks on Turkey.

The quick pace of the talks has riveted the public here.

“When I first started writing about this subject, I couldn’t even imagine it would come to this point,” wrote Eyup Can, the editor in chief of the newspaper Radikal, in a recent column. “In three months, Turkey is putting a stop to 30 years of bloodshed.”

For all the joy and celebration, there was still a sense of caution, and acknowledgment of a long road ahead.

“I see the statement as a positive development,” Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan said at a news conference in the Netherlands, where he was on a state visit. “Implementation, however, is much more important, as we hope to see at the earliest to what extent Ocalan’s statement will be accepted.”

While the effort to find peace carries political risks for Mr. Erdogan, it also carries huge possibilities. He faces some opposition from nationalist groups opposed to pursuing talks with the P.K.K., which is regarded as a terrorist group by the United States and the European Union. But the political gamble Mr. Erdogan has made is that successful talks could earn him the support of Kurdish lawmakers in Parliament for his effort to alter the constitution to create an empowered presidency that he would then seek in an election next year, analysts have said.

Mr. Ocalan’s direct involvement in the peace process, albeit while he is serving a life term in prison on a treason conviction, was itself a statement of how far the two sides have come. He had been barred from involvement in previous diplomatic efforts.

Murat Karayilan, the P.K.K. military commander, issued a statement from his mountain redoubt in northern Iraq in support of Mr. Ocalan’s call, NTV, a Turkish television channel, reported.

Hardened by the resentments from decades of persecution by the Turkish state, and mindful of past failed attempts at peace, some Kurds sounded a note of skepticism.

“If the state fools these people once more, hell would break lose, and we’d be forced to leave this land that will turn into a big ball of fire,” Zulkuf Gunes, 52, said, as he embraced his 2-year-old grandson dressed in a traditional Kurdish outfit in military green.

In Istanbul, Habibe Sezgin, a Kurd who moved to the city in the 1990s to escape the bloodshed in the southeast, expressed tempered hope. “I will hope and pray for peace,” she said, “but it is hard to believe in it after seeing so much violence over the years.”

Ceylan Yeginsu contributed reporting from Istanbul, and Tim Arango from Baghdad.