Culture Vulture — By Liana Aghajanian on February 1, 2012 3:18 pm

Born in 1954 in Izmir Turkey, photographer Aydin Cetinbostanoglu has been documenting Turkey’s Gypsy, Alevi, Jewish, Christian Arab and Armenian communities for years, forming relationships, building trust and as a result gaining exclusive access to cultural intricacies that have for the most part remained allusive to outsiders.

Hoping to break down cultural barriers, Cetinbostanoglu concentrated on documenting these various cultures for the last four decades, using photography as his tool to educate and expose Turkey to its cultural treasures.

“I shared both their happiness and sadness,” he writes on his website. “They looked at me laughing, smiling, worried and crying…I made many friends. How lucky I am, am I not?”

After exhibitions all over Turkey and in Italy, Germany and Yugoslavia as well as awards, Cetinbostanoglu spoke to ianyanmag about the art of photography, how he’s formed relationships with his subjects, how he’d like to travel to Armenia and what it felt like to photograph the last Christian Armenian village in Turkey.

An Alevi family in Turkey. This cultural and religious community numbers up to 15 million/ © Aydin Cetinbostanoglu

An Alevi family in Turkey. This cultural and religious community numbers up to 15 million/ © Aydin Cetinbostanoglu

Q. What inspired you to become a photographer?

A. When I was young, because of economic reasons, I had to learn a job and earn money. In 1960′s the only way to learn a job was working with a master. I had to choose this path. So, to become a photographer was more of a necessity. In 1966-1967, I spent my summer holidays working in a photography studio. In 1970 I took my first photograph with the camera which I borrowed from a friend. I was able to earn money by selling out to photos which I was took. Besides earning money, I started taking pictures by myself and showed them to my art teacher. He asked me why I was not opening my own photography exhibition and he sent me to a friend who manages a library. And I opened my first exhibition while I was a high school student in 1973.

Q. You have taken a great amount of photos and concentrated on minority cultures and ethnic groups in Turkey like the Alevis and Gypsies that are generally not photographed or talked about in the press a great deal. What is your interest in documenting these sub-groups and why do you think it’s important to do so?

A. After graduating from high school in 1973, I traveled around Anatolia with money I had saved. This was the first encounter with the people of Anatolia, and culture. I opened a photo exhibition with my first travel photographs when I returned. I studied political sciences at Ankara University Faculty of Political Science between1974 and1978. Both my earliest training as well as the turbulent era of economic and social events influenced the way in which we see the today’s photos.

I have witnessed many historical events during this period, and photographed them. In the Labor Day celebration in May 1977 while taking pictures, 37 people were killed. I saw and experienced their pain.

I continued to travel and photograph Anatolia. I shared people lives many times. I accepted the colors of different cultural traditions of the riches of Anatolia. These colors are to be photographed and documented.

A line of Gypsy girls in Turkey/ © Aydin Cetinbostanoglu

A line of Gypsy girls in Turkey/ © Aydin Cetinbostanoglu

Some of the estimated 40,0000 marchers who honored slain Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink last month/ © Aydin Cetinbostanoglu

Some of the estimated 40,0000 marchers who honored slain Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink last month/ © Aydin Cetinbostanoglu

Q. A big segment of your photography also has been documenting Armenians who live in Turkey. Why did you choose to do this and what have you learned from it?

A. There are Alevis, Gypsies, and Arabs in my photo works as well as Armenians. In fact, I have been photographing Gypsies since 1999, and the project is still ongoing. The difference in working with Armenians is that they have a richer cultural experience than some societies. We follow these “Masters of the Grand Bazaar” as well as in the church ceremonies and rituals. I began to work with Masters of the Grand Bazaar in 2006, establishing friendships over time which still exist.

I photographed a church wedding ceremony in 2010. I had forgotten my flash after the ceremony. When I came home I realized it and the day after I went to church again, people from the church gave it to me. I was affected by this honest behavior.

In the priest consecration ceremony which I photographed the pastor asked to the congregation about the candidate whether it is an obstacle. If a person says a negative response about the candidate, the ceremony would be cancelled. Everyone gave their positive thoughts, and the ceremony is completed. Even though this behavior is also a participatory ritual of the church, I was interested because it shows the structure.

These similar observations are in my projects about Armenians and carry it to the future.

An Armenian baptism ceremony in Turkey/ © Aydin Cetinbostanoglu

An Armenian baptism ceremony in Turkey/ © Aydin Cetinbostanoglu

Q. What are your thoughts about the Turkish Armenian community?

I certainly learned a lot from this culture during my work. Friendships are valuable for them.

I participated in Armenian Easter ceremonies in 2011 with my wife. We brought a bottle of liquor and parsley patterned Easter eggs painted with onion skins. After the ceremony, we put our eggs and liquor on the table. Some members of the community told us not to break our eggs. Instead, they took them to take home to keep. This behavior undoubtedly lies in the basis of respect for labor.

Q. Many of the minorities you have documented are fighting for equal rights in Turkey. From your interactions with them, what have you learned about their struggles and what do you think is the best solution to solve this problem?

A. The struggle for democracy is a necessity for everyone, and should be given to everybody. If this is provided it is possible to express themselves and protect their cultures.

Q. In your travels, you visited the last Christian Armenian village in Turkey, Vakifli. What was it like to be there?

A. Avedis is the oldest man of Vakıflı village who is also a friend of mine and he is the father of Artin. During Astvadzazin festival in 2009 I was the guest of that family. Avedis is a living history. He told me about history of the village and took me to the past. He had relatives living abroad. All of us created a large group and participated to the festival.

Vakifli is the only Armenian village in Antakya city located in South Turkey. Every year in mid August thousands of Armenians meet there and celebrate their religious holiday called Aztvadzadzin. On the first day, the priest of the church blesses the “salt” as a first step of the celebrations. Village women and men begin to prepare the traditional food “Harisa” (Largely used as “keskek” in Anatolia). Meats boil in seven large cauldrons during the night till morning. Seven symbolizeseven villages living in the past on the “Muse Mountain.”

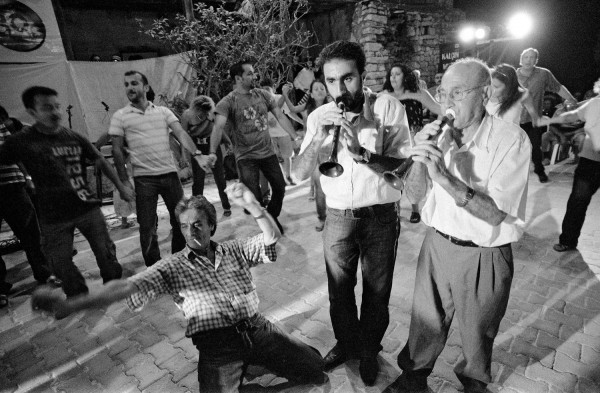

During the night people dance and have fun with traditional music and Armenian songs. On the second day, the priest blesses the grapes and organizes a religious ceremony in the garden of the church. After the ceremony, he blesses the “Harisa” before distributing to the people. Then village people share the food.

A scene from a celebration in Vakifli, Turkey’s last Armenian village/ © Aydin Cetinbostanoglu

A scene from a celebration in Vakifli, Turkey’s last Armenian village/ © Aydin Cetinbostanoglu

Avedis’ uncle told me that a big part of Armenians living there left the villages and went to Lebanon after the French withdrawal. A sad story. If the people in the seven villages could be alive, that area would be richer. Today they are busy with organic agriculture and provide higher value-added agricultural products to the market. At the festival time population was around 2500-3000 people with guests, after the festival the village population is around 100.

Q. How do you establish a relationship with the people who you are photographing? Is it difficult? Are they accepting you to photograph them or do they need to be convinced? How do you approach them?

A. One of the founder of Magnum Agency, Robert Capa has a nice saying: “Your photo is not close enough to the subject if it is not nice,” he says. This means “Be a part of the subject.” I also use this philosophy for myself. I take photographs with people and cultures of Anatolia for a long time. Because of this I can work with them more easily and have nice relationships with them today. I share life with them and over time, the photo subjects come to me.

Two Alevi women in Turkey/ © Aydin Cetinbostanoglu

Two Alevi women in Turkey/ © Aydin Cetinbostanoglu

Q. What subjects or people have you not photographed yet that you would like to, and why?

First of all I’d like to visit Armenia and take photographs. The most important reason is to combine them with my works and create a whole Armenian work. Another option would be India which is a big country where many cultures live together. I would like to walk around extended periods of time and do a colorful study. Because of the ancient cultures of Mexico, Egypt and the Far East are some of my future projects.

Q. What do you hope people take away from your photography?

A. I wish people who follow my work could think a little more about these cultures and appreciate them.