Turkey Cannot Open Its Borders to the

Heinous, Rancorous Tyranny of Armenia

Prof. Dr. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis March 15, 2009 ![]() –

–

If Turkey should be further democratized and harmonized with Europe, then why should Turkey open its borders to Armenia – a criminal tyranny denounced as such by the HRW in a lengthy and devastating Report?

In four earlier articles entitled “Turkey´s Ongoing Colonization: Only Reason for Recognizing Racist Armenian Tyranny” ), “Devastating HRW on Armenian Tyranny Imposes Cancellation of the Gul – Erdogan Pro-Armenian Policy” ), “Recognition of the Armenian Tyranny by Ankara Equals Colonization of Turkey by Freemasonic EU – US” ) and “Turkish – Armenian Rapprochement to Be Linked on Human Rights Conditions´ Improvement in Armenia” ), I republished parts of the devastating HRW Report (the HRW Press Release issued on the occasion of the Report publication a few days ago, the Contents, the Summary, the Methodology, the Background, and the 2008 Presidential Elections).

I called for a master coup against the unrepresentative Erdogan gang of high traitors, freemasons and besotted pseudo-Islamists, who implement the Anti-Turkish colonial agenda of England and France; in fact, the colonial powers imposed on the Freemasonic pupils Gul and Erdogan the Turkish – Armenian rapprochement.

In the present article, I republish the HRW Report chapter on the Post-Election Protests and Violence. In forthcoming articles, I will republish further parts of the devastating HRW Report on the Armenian Tyranny.

V. The Post-Election Protests and Violence

Overview

Prior to election day, Levon Ter-Petrossian had called on his supporters to gather in Yerevan on February 20-when preliminary election results would be known-for either a victory or a protest rally depending on the outcome.[43]From February 21 a continuous protest was installed on Freedom Square (also known as Opera Square), on the north side of Yerevan city center. Daily, several thousand protestors would gather to hear opposition leaders speak, and each night a group of protestors stayed in front of the National Opera House on Freedom Square, mostly in tents, their numbers varying from a few hundred to just over a thousand.[44]

The authorities allowed the protest encampment and rallies for nine days. Ararat Mahtesyan, first deputy chief of national police, told Human Right Watch that although the demonstration was illegal-it was being conducted without permission from the Yerevan city authorities[45]-it was initially tolerated as the Central Election Commission had not announced final results of the presidential election, and police investigations into election day complaints were still ongoing.[46]Â

The Yerevan mayor’s office issued a statement on February 25 saying the protests were unauthorized, “in violation of the law on assembly, rallies, demonstrations and marches,” and urging demonstrators to call a halt to them.[47] Two days later the Armenian police issued a statement urging an end to the unauthorized rallies, saying that “the police are fully resolved and intend to protect the constitutional order in the country and public safety within the bounds set for it by the law.”[48]

The authorities moved to suppress the protests on March 1, and in several episodes of violent confrontation between law enforcement officials and protestors, at least eight protestors and two police officers were killed and more than 130 people were injured. President Kocharyan announced a 20-day state of emergency under which all public gatherings and strikes would be banned, and freedom of movement and independent broadcasting severely limited. The events of March 1 are described in detail below.

Armenia’s International Legal Obligations on Police Use of Force

Governments are obligated to respect basic human rights standards governing the use of force in police operations, including in the dispersal of legal or illegal demonstrations. These universal standards are embodied in the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials.[49] The Basic Principles provide the following:

Law enforcement officials, in carrying out their duty, shall, as far as possible, apply non-violent means before resorting to the use of force and firearms. They may use force and firearms only if other means remain ineffective or without any promise of achieving the intended result.

When using force, law enforcement officials shall exercise restraint and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offence and to the legitimate objective to be achieved. Law enforcement officials must seek to minimize damage and injury.[50]

With respect to the dispersal of assemblies that are unlawful but non-violent, “law enforcement officials shall avoid the use of force or, where that is not practicable, shall restrict such force to the minimum extent necessary.”[51]

The European Convention on Human Rights requires all states to prohibit and prevent the arbitrary taking of life and the infliction of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment especially by state officials. Case law of the European Court has confirmed that police authorities must prepare and carry out operations to minimize any risk to people’s lives, and to completely prohibit ill-treatment. Where there is evidence that the police have taken a life or committed inhuman or degrading treatment, the authorities must ensure that there is an open investigation leading to the investigation and prosecution of any police officer responsible.[52]

The Council of Europe’s European Code of Police Ethics states that “police shall use force only when strictly necessary and only to the extent required to obtain a legitimate objective” and that “police must always verify the lawfulness of their intended actions.”[53]

A recent viewpoint issued by the Council of Europe’s Human Rights Commissioner Thomas Hammarberg, on impunity for police violence, states that “illegal behaviour by policemen is particularly serious as the very role of the police in a democratic society is to defend the population against crime, including violent crime. When the law enforcement forces themselves break the law, the whole system of justice is derailed.” Citing European Court of Human Rights case law, the commissioner noted also that “[t]he use of force is justified only in a situation of absolute necessity and should be practiced with the maximum restraint.”[54]Â

The statements Human Rights Watch took from demonstrators and bystanders suggest that the first police action, in the early morning of March 1 against the Freedom Square tent encampment, entailed excessive use of force, without warning and in the absence, at the start, of resistance. Although later protestors began throwing stones at police from side streets near Freedom Square, one participant described being beaten up by police who found him lying on the ground.

The events that unfolded later in the day were both more violent and more contentious. Sections of the very large crowd gathered near the French embassy appear to have been armed with metal rods, sticks, paving stones, and even petrol bombs, and seem to have initiated some of the clashes with police, such as at Yerevan City Hall on the afternoon of March 1. On the other hand, participants’ statements to us show that police, in their actions that evening to end the demonstration, opened with overly aggressive measures (tracer bullet fire and teargas, and no verbal warnings to disperse), and used excessive force against people who were not physically challenging them. As protestors then responded with using force against police, at least some of the fatalities appear to have occurred because police discharged their firearms deliberately in circumstances where lethal force was not called for, or through improper use of crowd control measures, such as firing teargas canisters at close range.Â

Armenia’s obligation to investigate all allegations of excessive use of force by police is discussed below, in Chapter VI.

The March 1 Events in Detail

Early morning removal of protestors and protest camp at Freedom Square

On the night of February 29 to March 1, several hundred protestors were on Freedom Square, staying in some 25 to 30 tents.[55] Police moved against the protestors’ camp early on the morning of March 1.

According to first deputy police chief Ararat Mahtesyan, speaking to Human Rights Watch four weeks later, the police had arrived at the square on March 1 to conduct a search, acting on information that demonstrators had been arming themselves with metal rods, and possibly firearms, in preparation for committing acts of violent protest on March 1. Mahtesyan said that initially a group of 25-30 police officers, including experts and investigators, were sent to do the search of the protestors’ camp. When the group tried to conduct the search, the protestors turned aggressive and resisted police with wooden sticks and iron bars, resulting in injuries to several policemen. At that stage more police had to be deployed and had to use force to disperse the crowd and support the group conducting the search. According to Mahtesyan, this operation lasted for about 30 minutes and 10 policemen sustained injuries as a result.[56] Despite Human Rights Watch’s request, Mahtesyan did not provide any details about these injured police and the nature of the injuries they sustained.[57]

Several witnesses interviewed separately by Human Rights Watch consistently described a different sequence of events in front of the Opera House on the morning of March 1. According to them, sometime shortly after 6 a.m., while it was still dark and as demonstrators started waking, news spread that police were arriving at Freedom Square. Hundreds of Special Forces police in riot armor, with helmets, plastic shields, and rubber truncheons, started approaching the square, in four or five rows, from Tumanyan Street and Mashtots Avenue.[58] Police surrounded the square and stood there for a few minutes.[59]

Levon Ter-Petrossian, who had been sleeping in his car parked at the square, was woken up. According to the account he gave Human Rights Watch, he addressed the protestors, some of whom by this time were out of their tents, asking them to step back from the police line, and then to stay where they were and wait for instructions from the police. He also warned the police that there were women and children among the demonstrators.[60]

Even before Ter-Petrossian finished his address, police advanced towards the demonstrators in several lines, beating their truncheons against their plastic shields. According to multiple witnesses, the police made no audible demand for anyone to disperse nor gave any indication of the purpose of their presence. They started pushing demonstrators from the square with their shields, causing some to panic and scream and others to run. Some demonstrators appeared ready to fight the police, which was why, according to Ter-Petrossian, he urged the crowd not to resist the police. Others were still in their tents.[61]

Immediately afterwards, without any warning, riot police attacked the demonstrators, using rubber truncheons, iron sticks, and electric shock batons. According to Ter-Petrossian, a group of about 30 policemen under the command of Gen. Grigor Sargsyan approached him and forcibly took him aside. When asked if he was arrested, Ter-Petrossian was told that police were there to guarantee his safety and that he was requested to cooperate.[62] Levon Ter-Petrossian was subsequently taken home and effectively put under house arrest.[63]

Vahagn V., a 42-year-old economist who had spent the night on the square in front of the Opera House, gave this account:

Without any warning police just started beating truncheons on their shields, making loud noises that created chaos. In a minute or so they started attacking from the side of Tumanyan and Mashtots. They switched off the microphones and electricity. It was still dark. The only lights I could see were small red lights that I thought were flashlights, but they turned out to be from electric shock devices. One of them touched me on the left hand and it burnt my skin. They were attacking from all sides and beating people. Women were screaming. We ran. It was complete chaos…[64]

At least two witnesses described to Human Rights Watch how police ripped off the ropes supporting the tents and as the tents collapsed the police continued assaulting, with their truncheons, people who were still inside.[65] Gagik Shamshyan, a photo correspondent for political opposition newspapers who attempted to photograph the raid, was assaulted by police and then detained. He told Human Rights Watch:

Policemen in riot uniforms in helmets, shields, and truncheons were beating the protestorsâ EURO |. They were also pouring buckets of water on the tents and continued to assault with truncheons. I was shooting photos and after making about 20-25 shots, some policemen saw my camera’s flash and about 15 of them attacked me. One of them recognized me and instructed others to beat me â EURO | Another one grabbed my camera and hit me with a truncheon on my back. I fell down and they continued to beat me with truncheons and kick me. They handcuffed me and were pulling my hands from behind. It was very painful … Two of them grabbed me by my jacket and dragged me for about 40 meters, with my face down on the pavement. Another officer who recognized me shouted, “Beat him! He writes bad stuff about us …” [He] approached me and threatened to gouge my eyes out, and even pushed his finger to my eye. I was terrified …[66]

Police kept Shamshyan on the ground for about 20 minutes, assaulted him periodically, and then drove him to the central police station.[67] He was later released.

A 54-year-old artist, Sanasar S., gave Human Rights Watch the following account of what happened to him that morning:

There were at least as many police in riot gear as people gathered in front of the Opera. Without saying anything police surrounded us and attacked us with truncheons and electric shock devices. People panicked and started running away. I ran together with about 20 protestors towards the Northern Avenue, chased by the riot police. At the intersection of Pushkin Street and Mashtots Avenue about six of them caught up with me. I felt a blow to my head and I fell on the ground, losing consciousness. When I regained my senses I was surrounded by police. Two of them were holding me on my feet as I could not stand. My shoulder ached and my nose was bleeding.[68]

It turned out that Sanasar S. had sustained a broken arm. His subsequent detention is described below in Chapter V.

Murad M., age 30, told Human Rights Watch that a police officer chased him off the square and hit him on the head, causing him to lose consciousness. “I momentarily lost consciousness after a blow on the head, and fell … When I came to my senses, my brother was carrying me away from the square. My head was bleeding and my hat was all covered in blood.”[69] Murad M. required seven stitches on the right side of his forehead. He sustained bruises to his right hand, back, and legs. Fearing arrest, he refrained from going to a hospital and instead sought medical assistance from a private doctor.[70]

Hovsep H., a 32-year-old designer, ran from the square with a group of about one hundred others, with the police chasing them. The group thinned out as some people split off, and was in a stop-and-go chase with police for about an hour. At times the group threw stones at the police. When police finally caught up with Hovsep H., he was assaulted. He told Human Rights Watch:

I felt very tired and could not run anymore. I tried to get into an apartment block entrance, but it was locked. Three or four police ran after me. I felt really exhausted and decided to lie down and cover my face with my hands to protect it. Policemen who were after me started beating me. They were using truncheons and kicking me with their boots. They were beating on my back, head, and kidney area. I felt a huge blow on my head and I lost the feeling of reality, I could not even feel pain anymore and it all felt like a dream. I don’t remember anything else, but when I regained my senses, my head was bleeding and the jacket I wore was all bloodied. I was already in a police station by that time.[71]

Hovsep H.’s experience of further ill-treatment in detention is recounted in Chapter V.

As a result of the early morning police actions on Freedom Square, 31 people were officially reported to be injured, including six policemen.[72]

The police claimed that after the demonstrators were dispersed they found a stock of real and makeshift weapons, including “three guns, 15 grenades, two bullet cases and 138 bullets of various calibers, plastic explosives, big number of makeshift weapons, syringes and drugs.”[73] All witnesses and victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch claimed that the alleged arms cache was planted after the demonstration was dispersed. The chairman of the ad hoc parliamentary commission established to investigate the March 1 events told Human Rights Watch in January 2009 that he had not seen any evidence linking the arms cache to the demonstration’s participants or organizers.[74]

Notes

43] OSCE/ODIHR, “Post Election Interim Report, 20 February â EURO” 3 March, 2008.” Addressing a mass rally in the capital Yerevan on 16 February, Ter-Petrossian warned the authorities that a rally planned by his supporters in Yerevan on February 20 would turn into open-ended protests if the election was rigged. Reported by Arminfo, February 16, 2008.

44] Human Rights Watch interviews with Vahagn V., Yerevan, March 13; Hovsep H., Yerevan, March 26, 2008, Arsen A., Yerevan, March 28; and Ararat Mahtesian, first deputy chief of the Police of the Republic of Armenia, Yerevan, March 28, 2008.

45] Â According to legislation in force at the time, organizers of mass public events had to notify the head of the community where the event was being held at least three working days in advance. Law on Conducting Meetings, Assemblies, Rallies and Demonstrations, 2004, as amended by the law adopted on October 4, 2005, http://www.legislationline.org/documents/action/popup/id/6628Â (accessed January 16, 2009), art. 11. Ter-Petrossian’s campaign notified the Yerevan city government that it would hold a rally on February 20 in Yerevan. However, the campaign did not lodge a notification with the city government on the subsequent assembly in Freedom Square from February 21 onwards. See OSCE/ODIHR, “Post-Election Interim Report, 20 February â EURO” 3 March 2008.”

46] Human Rights Watch interview with Ararat Mahtesian, Yerevan, March 28, 2008.

47] “Armenian capital’s mayor urges protestors to stop unsanctioned rallies,” Arminfo (in Russian), February 25, 2008; and “Armenian Officials Demand End To Election Protests â EURO” AFP,” Dow Jones International News, February 25, 2008.

48] “Armenian Police urges opposition to suspend rallies in capital,” Arminfo (in Russian), February 27, 2008.

49] Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, adopted by the Eighth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders, Havana, 27 August to 7 September 1990, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.144/28/Rev.1 at 112 (1990).

50] Ibid., principles 4 and 5.

51] Ibid., principle 13.

52] See, for example, Nachova and Others v. Bulgaria, Application No. 43577/98 and 43579/98, Grand Chamber Judgment of 6 July 2005

53] Council of Europe Committee of Ministers, Recommendation Rec(2001)10 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on the European Code of Police Ethics (Adopted on September 19, 2001 at the 765th meeting of Ministers’ Deputies), (accessed September 1, 2008), paras. 37-38.

54] Thomas Hammarberg, “There must be no impunity for police violence,” Viewpoint of the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, December 3, 2007, (accessed December 3, 2007).

55] Ibid.; Human Rights Watch interview with Gagik Shamshyan, photo correspondent for Aravot and Chorrord Ishkhanutyun newspapers, Yerevan, March 12, 2008.

56] Human Rights Watch interview with Ararat Mahtesian, Yerevan, March 28, 2008.

57] Ibid.

58] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Sanasar S., March 1, 2008; Human Rights Watch interviews with Vahagn V., March 13; and Arsen A., March 28, 2008.

59] Human Rights Watch interview with Levon Ter-Petrossian, Yerevan, March 29, 2008.

60] Ibid. This was confirmed by all witnesses and victims of the event interviewed by Human Rights Watch.

61] Â Ibid.; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Sanasar S., March 1, 2008; Human Rights Watch interviews with Vahagn V., March 13; and Arsen A., Yerevan, March 28, 2008.

62] Human Rights Watch interview with Levon Ter-Petrossian, Yerevan, March 29, 2008.

63] Ibid.

64] Human Rights Watch interview with Vahagn V., March 13, 2008.

65] Ibid.; Human Rights Watch interview with Gagik Shamshyan, March 12, 2008.

66] Ibid.

67] Ibid.

68] Human Rights Watch interview with Sanasar S., March 26, 2008.

69] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with interview with Murad M., March 1, 2008.

70] Ibid.

71] Human Rights Watch interview with Hovsep H., Yerevan, March 26, 2008.

72] “Thirty-one injured as Armenian police disperse opposition rally,” Arminfo (in Russian), March 1, 2008. The report quoted Ministry of Health information.

73] Human Rights Watch interview with Ararat Mahtesyan, March 28, 2008. See also, OSCE/ODIHR, “Post Election Interim Report, 20 February â EURO” 3 March, 2008,” March 7, 2008, (accessed June 10, 2008).

74] Human Rights Watch interview with Samvel Nikoyan, Yerevan, January 13, 2009.

Note

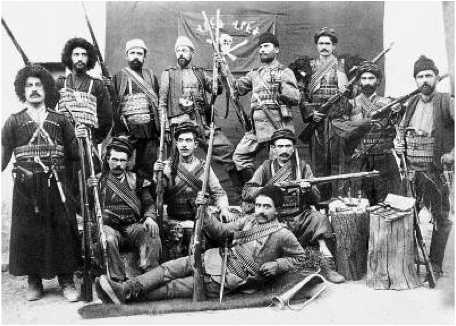

Picture: Garni Mithraeum, a temple dedicated to Mithra, the Iranian god of the Ancient Armenians. Before being misunderstood and misused by the Armenian state authorities and academia, Armenian History has been totally falsified by the colonialist historians and philologists of France and England, who projected in it a touch of Hellenism, one of their fabrications that has never had any real effect in Armenia. It was all geared in order to set up a false sense of Greek – Armenian – Western European Anti-Islamic, Anti-Ottoman, and Anti-Turkish alliance which was a total catastrophe for all these Oriental populations and a real success for the colonial elites of France and England. Ancient Armenia is definitely a para-Iranian state that, although constantly opposed to the Persian supremacy within the wider Iran area, greatly contributed to the diffusion of Mithraism, a totally Iranian religion, among the Greek speaking peoples of Anatolia, the Aegean Sea and the Balkans, and further beyond throughout the Roman Empire and Northern and Eastern European territories out of the Roman imperial control.