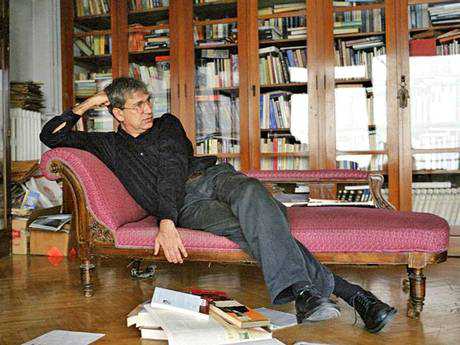

The view from the balcony of Orhan Pamuk’s apartment in the hilly Istanbul district of Cihangir is almost absurdly apt. The minarets of the Cihangir mosque are in close enough proximity that the muezzin’s amplified call to prayer renders all conversation impossible; across the Golden Horn stands Topkapi Palace, seat of the Ottoman sultans; further away still are the high-rise towers and business centres that drive the new Turkish economy.

The view pans across the Bosphorous from the European side of Istanbul, with its tourist sights and expat-heavy districts, across to the Asian side, Anatolia. Taken together, it is a neat empirical manifestation of the philosophical, cultural and geopolitical dilemmas that Turkey’s best-known writer explores in his novels.

Pamuk, who turned 60 earlier this summer, has been writing books about Istanbul for three decades, and was honoured in 2006 with the Nobel Prize for literature. Istanbul has a competitive claim to be one of the world’s greatest cities, and the prominence of Pamuk as its most prescient contemporary chronicler is undisputed.

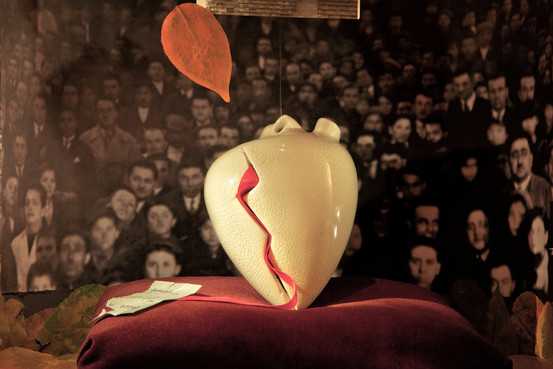

This status has been further boosted in recent months with the opening of the Museum of Innocence, which is designed as the counterpart to his most recent novel, of the same name, which came out in 2009.

“It was conceived together, I planned it together – I wrote the book thinking of the museum and I made the museum thinking of the novel,” says Pamuk, sitting out on his balcony in the hot sun. Prior to beginning work on the novel, in 1998, he bought a house in the down-at-heel Cukurcuma district, and made it the location where one of the novel’s protagonists, Fusun, would live.

The book and museum are a detailed evocation of the 1970s and 1980s in Istanbul, and Pamuk spent years scouring the flea markets of the area looking for objects that would fit into his novel. “It’s not that I wrote the novel and then looked for the objects. First I would find an object which I would think is suitable for my characters and stories, then write about it, and in the end I ended up with a house full of thousands of objects,” he says. Simultaneously he worked with architects on a project to turn the building into a museum to house the objects, which opened its doors earlier this year.

The Museum of Innocence charts the obsession of Kemal, a well-to-do young man from the posh Istanbul suburb of Nisantasi, with a young cousin, Fusun, from a less wealthy side of the family. His obsessive love, which verges on creepy infatuation, leads to his emotional destruction, and he hoards objects with connections to Fusun with the intention of building her a shrine – the museum.

The most striking exhibit is in the lobby, a collection of 4,213 cigarette stubs allegedly smoked by Fusun and pilfered by the love-struck Kemal between 1976 and 1984. The cigarettes are pinned to the walls in neat rows with an entomologist ‘s precision, each butt bearing a handwritten caption capturing a moment of Fusun’s thoughts, or of events in Istanbul at the time.

Pamuk went to painstaking lengths to get the exhibit right. “If you put real tobacco there, it will be spoilt in six months, and it would have been completely ruined,” he says. Instead, 4,213 cigarettes were emptied then filled with a chemical compound made specially to look like tobacco. They were then smoked using a vacuum cleaner, stubbed out using various levels of thoroughness and aggression depending on Fusun’s supposed mood at the time of smoking, and scarlet lipstick was applied to the ends.

“At the beginning we overdid it a bit so then we had to clean them and do it all again,” says Pamuk. “Fusun doesn’t wear that much lipstick!”

Given the painstaking attention to detail that Pamuk has put into the beautifully curated museum, and the fact that Kemal is a character from a background not unlike his own, there is a natural impulse when reading the novel to wonder how much the author is drawing a self-portrait.

“Everyone asks me, especially women readers, ‘Oh, Mr Pamuk, are you Kemal?’” he says. “No, I’m not, I’m not as obsessive as him, and I was never infatuated with love like this, although of course we all do have things similar to this at some time in our lives. But where I identify with him more is not in terms of my infatuations, but because I too fell out of my class.

“I’m not in touch with the Nisantasi bourgeois class in which I grew up, just like Kemal at the end of my novel. Him because they made fun of him falling in love, and me because of politics and literature, which those people never cared much for.”

Pamuk has fallen foul of more than just his social peers in recent years. A combination of books such as Snow that explore the fault-lines dividing Turkey and outspoken comments about the massacres of Armenians during and after the First World War gave him a certain notoriety. He received death threats, and underwent a trial in 2005 for “insulting Turkishness”.

“The campaign of the right-wing press against me continued until 2010, and I felt very uncomfortable, but now I’m much more relaxed,” he says. “Perhaps it’s partly the Nobel Prize, but also the country has changed. I was promoting Turkey joining the EU, and that whole project fell apart, so the nasty energy against its proponents disappeared.”

Now, he says, things are easier, although we are still discreetly trailed by his government-appointed bodyguard when we take the 15-minute walk from the museum to his apartment. The bodyguard, and the stares from the public when they spot Turkey’s most famous intellectual walking by, are irritating for someone who values solitude, but the biggest toll is on his creative energy, says Pamuk.

“Being a fiction writer makes you someone who works with irresponsibility. When there are these campaigns against you, you watch your word; you don’t want more of that. One of your characters says something in a playful mood, and then it gets out of control.”

His unofficial anointing as the leading voice of a Turkey caught between East and West, religion and secularism, tradition and modernity, is equally unhelpful, he says.

“It’s a burden. People look at me as sort of a diplomat for Turkey, which by nature, I’m not; I don’t want to be. It’s again about that playfulness. Being Turkey’s voice or representative is not playful, it’s not childlike; it makes me self-conscious, kills the child in me.”

He was able to give freer reign to his creative side in the curating of the museum. “Between the ages of seven and 22 I wanted to be a painter, so part of creating the museum was to answer this calling,” he says. Some pieces were easy to find, such as old bottles or pictures of Istanbul boats of the 1970s, but items like old toothbrushes or salt shakers were harder to come by.

“The museum honours daily life objects we don’t notice, their emergence and disappearance,” he says. “You have an intimate relationship with your salt shaker, you sit and look at it three times a day. And then one day, it breaks, or someone buys you a new one, and it’s gone. After they disappear, five or 10 years later you see them in flea markets, and then they disappear from there too.”

“Globalism washes away memories,” says Esra Aysun, the museum’s director. “Back then we were like Eastern bloc countries – we were living a secret, isolated life. Now, Istanbul is becoming a duplicate city like every other city in the world and some of these objects are very precious for our cultural memories.”

Pamuk is currently in the middle of writing a new novel, which he says will be called A Strangeness in my Mind. His writing process involves locking himself away in the Cihangir apartment, where he is surrounded by shelves of books and inspired by the view out to the Bosphorous and the Sea of Marmara. He writes by hand, using a computer only for email.

The new novel will follow the life of a migrant who comes to Istanbul from Anatolia in 1969 to seek his fortune, and becomes a street vendor, hawking yoghurt. It will follow its hero through several decades to the present day. “It will track the journey from the gecekondu, the shanty towns, to these strange high-rises raising their heads now,” he says, waving a hand in the direction of the new constructions over on the Asian side of the Bosphorous.

The novel, providing a sweeping view of Istanbul over the past half-century, seems unlikely to let him shed the unwanted mantle of being the voice of Turkey. All of Pamuk’s novels have been set in Turkey and, while he does not rule out writing something on a completely different topic, he says it is probably unlikely.

“I write about what I know. I may write a science fiction novel one day, but, even if I did, everyone would read it as being about Turkey,” he says, with a loud and hearty laugh. “And they would be right!”

A writer’s life: Orhan Pamuk

* Born in Istanbul in 1952.

* He was born to a wealthy if declining family and lived with his mother during his 20s, trying at the same time to find a publisher.

* He found fame with his first novel Darkness and Light winning the Milliyet Press Novel Contest in 1979.

* It was in 1990 that he first gained international acclaim with The Black Book.

* His two most famous novels, My Name is Red (2000) and Snow (2002) eventually led to Pamuk being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2006.

* In 2005, the Turkish authorities opened criminal proceedings against him after he apparently acknowledged Turkish responsibility for the killing of more than a million Armenians between 1915 and 1923. The charges were dropped a year later.

‘I write because I need to’

“The question we writers are asked most often is: why do you write? I write because I have an innate need to. I write because I can’t do normal work. I write because I want to read books like the ones I write. I write because I am angry at everyone. I write because I love sitting in a room all day writing. I write because I can partake of real life only by changing it. I write because I want the whole world to know what sort of life we live in Istanbul, in Turkey. I write because I love the smell of paper, pen, and ink. I write because I believe in literature, in the art of the novel, more than I believe in anything. I write because it is a habit, a passion. I write because I am afraid of being forgotten. I write because I like the glory that writing brings. I write to be alone. Perhaps I write because I hope to understand why I am so very, very angry at everyone. I write because I like to be read. I write because once I have begun a novel, I want to finish it. I write because everyone expects me to write. I write because I have a childish belief in the immortality of libraries, and in the way my books sit on the shelf. I write because I have never managed to be happy. I write to be happy.”

Nobel Prize for Literature lecture, 7 December 2006