By: Kadri Gursel for Al-Monitor Turkey Pulse. Posted on March 12.

Turkey’s future is to be decided by the nation’s three most powerful men, by the equilibrium they shape among themselves and by deals they forge with each other.

|

Recep Tayyip Erdogan leaves a wreath-laying ceremony at the mausoleum of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, founder of modern Turkey, in Ankara, Aug. 1, 2012. (photo by REUTERS/Stringer)

|

About This Article

|

Summary : Kadri Gursel writes on the three men who are critical to Turkey’s future: Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan; Abdullah Ocalan, imprisoned head of the Kurdistan Workers Party [PKK]; and Fethullah Gulen, exiled head of the Gulen Sunni movement.

Original Title: |

The first and the most powerful is already at the zenith of political power: Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. He is also the most powerful, most capable civilian leader after the founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. His colleagues who know from his younger days speak of him as “reis,” [”president” in formal usage and ”chief” colloquially]. The people who joined him at his current post call him “patron” [the boss]. In official bureaucratic milieu, among party members and businessmen close to him he is “beyefendi” [sir or esquire]. Not only is he the most powerful man of Turkey, but because he enjoys exercising his power and doesn’t want to share it with anyone else, he is a personality that instills fear in his party AKP, in the state structure and the society.

The second most powerful man is serving a life sentence and has been in prison for 14 years: Abdullah Ocalan, who founded the separatist, armed Kurdish organization, the Kurdistan Workers Party [PKK] in 1978 and who personally led it until 1999 when he was apprehended in Kenya and handed over to Turkey. Since his imprisonment the PKK has changed drastically. The Kurdish issue became politicized and regionalized and has become a mass movement. Among many political and societal variables the key issue that hasn’t changed in the Kurdish movement has been the loyalty to Ocalan’s historical leadership. This is why the Kurds close to the PKK say “Honorable Ocalan’’ or in brief “the Leadership” when they speak of him. Ocalan is a figure that unites Kurdish nationalists.

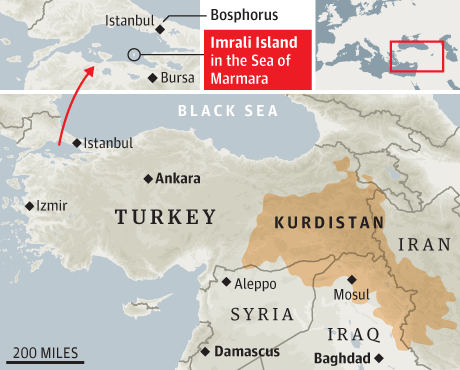

The AKP rule and their media use a code for Ocalan that is derived from the name of the island where his private prison is: Imrali.

Those in the power, to avoid perceptions that they are in a dialogue with Ocalan through intelligence officials, refrain from using his name and prefer to say “Imrali.”

The third powerful man is a Sunni religious leader living in voluntary exile in the United States for 14 years: Fethullah Gulen. Gulen, who started out as a mosque imam, is the founder of an Islamic socio-political movement that is now spread worldwide. He is its spiritual leader. The movement has several labels: “Gulen Movement,” “Service” or the most popular version in Turkey, “Cemaat” [a congregation or faith community]. Their followers are known as “Gulenists.” Those who admire Fethullah Gulen call him “hocaefendi” [a scholar esquire].

Those who don’t like him call him ‘’Pennsylvania’’ after the state he moved to in 1999 when he left Turkey because of military pressure. Some call him “Across the Ocean.”

The main engine of the Gulen Movement that has long become globalized is education. They have close to 1,000 schools in more than 120 countries, including universities.

In Turkey they have a nationwide school and student hostel network with tens of thousands of teachers and hundreds of thousands of students. Vast majority of their students are on scholarships. The revenues that turns the wheels come from their capitalist ventures and donations collected by a network of organizations of powerful businessmen. The movement also has a strong media network with daily Zaman and Samanyolu TV channels as its flag ships.

But the most extraordinary political power attributed to the Gulen Movement is the network it has reportedly built inside the state mechanism, especially in judiciary and security sectors.

Today, many impartial observers agree that the current neo-Islamist rule of Turkey has been able to eliminate in just three years the military-bureaucratic tutelage power centers that saw themselves as the guardians of the Ataturk Republic with police actions and judicial procedures mainly thanks to harmonious work of the Gulenist cadres in the police and the judiciary.

Although their statures are widely divergent, there are commonalities in the leaderships of Erdogan, Gulen and Ocalan that render them powerful and consequential.

All three are extremely charismatic, all three have exceptional influence on their constituencies, all three are visionaries and finally all three have alternative societal projects. All three with their visions and leaderships carried changes they brought about to outside of Turkish borders.

And there is no fourth man who has similar attributes.

Until recent past, chiefs of general staff used to be counted among the powerful figures of the land but not anymore. Turkey has changed and will change more.

The change in Turkey now proceeds on two axes: Erdogan’s overly personalized authoritarian president project, and peace with the Kurdish movement.

What Turkey’s new regime will look like and status of Turkey’s relations with the Kurdish reality in the Middle East will largely be determined by the interaction between these two axes.

To make is clearer and more concrete we must say this: Although there was no cause-and-effect relationship, the a la carte presidential model Erdogan wants for himself and settlement of the Kurdish issue became linked to the peace negotiations at Imrali. Despite efforts to keep them under wraps, it is now known that the negotiations between Turkish intelligence officials who represented Erdogan’s authority and Ocalan have been going on since last October.

The negotiation platform of a “new constitution” on which the presidential system and peace issues were debated was in a format of give-and-take.

For the presidential system Erdogan desires, a constitutional amendment is required as well as for the settlement of the Kurdish issue. To meet the equality demands of the Kurds a neutral definition of citizenship that doesn’t require “Turkishness,” education in the mother tongue and partially fulfilling the demand for autonomy by empowering local administrations are all required constitutional adjustments.

If progress is wanted in the peace process, then the constitution has to be amended to meet these Kurdish demands. Erdogan’s AKP doesn’t have enough parliamentary seats to submit a constitutional draft to a public vote. AKP can negotiate only with the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party [BDP] for a presidential system. Other parties are categorically refusing to negotiate for such a system.

A reality emerged when the daily Milliyet on Feb. 28 published the minutes of the meeting three BDP parliamentarians held with Ocalan at Imrali a few days earlier. The topic of BDP supporting the presidential system was on the agenda of the Imrali meeting and Ocalan, despite some reservations, was amenable to support Erdogan’s presidency.

Nevertheless, it will not be easy for the Erdogan government to market a “AKP-BDP constitution” to majority nationalist conservative Turkish public unless the PKK military forces leave Turkey before a possible constitutional referandum in the fall and for Turkey’s 30-year terror question to be considered as done with.

An interesting feature of the “’Imrali Minutes” report was the harsh accusations of Ocalan against the Gulen Movement. Ocalan claimed the summons by the specially authorized prosecutor of Hakan Fidan, the undersecretary of National Intelligence Organization for questioning on Feb. 7, 2012, was “”actually a coup attempt” and implied it was the Gulen Movement behind it. Ocalan went as far as to claim that the objective of the summons was to arrest the prime minister on charges of treason and labeled the Gulen Movement as new “counter-guerrilla.”

We will perhaps understand better in the future why Ocalan made such severe accusations against the Gulen Movement. The Gulen media since 2009, especially after 2011, have been increasingly supportive of police operations that resulted in arrests of thousands of Kurdish activists, there has been a perceptible antipathy against the Gulen Movement in Kurdish public opinion. But this is not enough to explain Ocalan’s outburst.

What is definite is this: The crisis that began Feb. 7, 2012, with the summons for questioning of Hakan Fidan, the MIT undersecretary who happens to be one bureaucrat Erdogan trusts most, culminated in ending the de facto partnership for power between the Gulen Movement and the AKP.

It is true that the Gulen Movement, with its media assets, its undeniable influence over conservative voters and its potential power within the state, is a key actor. But what is apparent is that the movement has not yet decided its final position on Erdogan’s presidency and the peace process with the PKK and that they are somewhat undecided with these issues.

The Gulen Movement has adequate power to influence these processes this or that way once it makes up its mind.

The clarification of the interaction among “the three” also depends on the Gulen Movement to determine its inclination.

Kadri Gürsel is a contributing writer for Al-Monitor‘s Turkey Pulse and has written a column for the Turkish daily Milliyet since 2007. He focuses primarily on Turkish foreign policy, international affairs and Turkey’s Kurdish question, as well as Turkey’s evolving political Islam. He joined the Milliyet publishing group in 1997 as vice editor-in-chief of a newly launched weekly news magazine, Artı-Haber, and was Milliyet’s foreign news editor from 1999 until 2008. Gürsel was also a correspondent for Agence France-Presse between 1993 and 1997, and in 1995 was kidnapped by the PKK, an experience he recounted in his book Dağdakiler (Those of the Mountains), published in 1996. He is also chairman of the Turkish National Committee of the International Press Institute.

Read more: http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/03/erdogan-ocalan-gulen-turkey-pkk-peace-process-presidency.html#ixzz2NRFfoUTn

The momentum towards the “Imrali process” – as the incipient peace talks are being dubbed – has been provided by a series of tragedies and catastrophes both regional and within Turkey, apparently bringing both sides to conclude they have fought themselves to a stalemate.

The momentum towards the “Imrali process” – as the incipient peace talks are being dubbed – has been provided by a series of tragedies and catastrophes both regional and within Turkey, apparently bringing both sides to conclude they have fought themselves to a stalemate.