The trial of several journalists accused of being involved in an alleged plot to overthrow the Turkish government had degraded the status of press freedom in the country, writes Ece Temelkuran

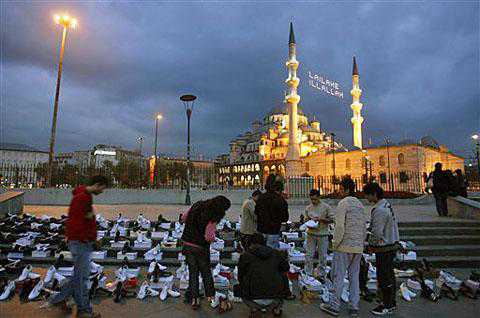

“We are spending our lifetimes running in between the courtrooms”, reads one of the tweets from outside the court. People are already talking about “the trial of the following day”. They are spending the night in the freezing cold weather of Istanbul and hoping that the court will release the 11 journalists who have been awaiting trial for almost a year. They are exchanging the dates of scheduled court cases against the journalists, students and politicians, complaining about the overlapping court dates.

Today in Turkey, there are more than 100 journalists, over 500 students and more than 3,500 Kurdish and Turkish politicians who have been subjected to political trials and imprisoned for months or even years. Figures from an Associated Press survey show that one third of the world’s terrorists live in Turkey.

Only a few journalists and some citizen reporters are reflecting the objective truth about what is going on in the country, since almost none of the national media dare to speak about these “terrorism cases”. TV networks don’t bother to mention their arrested colleagues. Instead they broadcast documentaries about aviation while the hearings are taking place, or they wait for 11 hours for the Prime Minister’s official statement to mention the 19 Kurdish children that have been killed in the recent bombardment.

It is important that citizens are following up with these cases, as they are the only ones who are supporting the arrested journalists facing trial by covering the news mainly on Twitter.

The case of investigative journalists Ahmet Şık and Nedim Sener, among those accused of being involved in an alleged plot to overthrow the Turkish government, is perhaps the most relevant example. The charges against these two reporters are quite blurry. “Causing political chaos through media” or being a member of a fake terrorist organisation are only two of the charges against them.

Both of them are accused of being members of Ergenekon, an illegal paramilitary organisation aiming to topple the government. Both men have been investigating the organisation for years; the argument in the indictment is that they are using their journalism as a cover for their real “terrorist” identity.

They have spent months in prison only to learn about the accusations and waited more than 11 months to have their first hearings. They are included in the Oda TV case, named after an internet portal deemed a hub for “terrorist activities”, with nine other journalists. Needless to say they were critics of the government.

It might be assumed that such a case would create enormous media attention and wide-ranging support from the colleagues. But no. Since Prime Minister Erdogan personally threatened the journalists who criticise this case, just a handful of reporters showed up in the court. Most probably, colleagues were afraid to end up like I did few days ago: Unemployed.

Or worse: ending up behind bars. As the indictment of the Oda TV case tells us, an email coming from a fake account is enough to link you to a terrorist organisation; an ordinary joke on tapped phone conversations might be considered “evidence” of “terrorist activities”. As Sener, in his defence statement during the hearing, put it: “The prosecutors don’t even bother to collect evidence against the journalists, let alone the ones in their favour”.

The inadequacy and absurdity of the indictment that caused constant laughter in the court was not covered by Turkey’s press. It was on the first page of the New York Times but not the national newspapers. In addition, during last week’s hearings the judge banned mobile phones in the court, although despite the danger of a six-month prison term for acting against the court’s order, a few brave colleagues tweeted from inside the court. They are the only ones who broke the silence.

Şık’s defence statement today was a historical and thorough answer to this age of silence in Turkey. He asked the question which most of the people don’t dare to ask even if they are not behind bars: “Is this a democracy or an empire of fear? I hope the silence of government is out of embarrassment!”

He has every right to ask the question because he has been in prison, in complete isolation for 11 months, for writing a book that that alleged the involvement of Turkish security forces in the 2007 murder of the Turkish-Armenian newspaper editor, Hrant Dink.

Unfortunately, it was not the ones who are supposed to answer Şık question but rather those who were brave enough to show up in court. They were all embarrassed when Sener cried when he said what mattered to him was to be judged by people’s hearts and minds, not by the court.

Our friends and colleagues have not been discharged. One of them, 65-year-old Dogan Yurdakal, was not allowed to see his wife for the last time when she was dying from cancer. When asked in the court about his marital status he said: “I was married but now I am a widow.”

These political arrests and the silence surrounding them has degraded the status of press freedom in Turkey. That is why colleagues are calling me nowadays, after hearing the news of my firing from Haberturk, to tell me that they are going to be unemployed, like me, sooner or later. They ask if there is any problem with the #freejournalists hashtag on Twitter, which we created to spread news about the Oda TV case. Not yet, is my answer. Not yet.

Ece Temelkuran is the author of ”Deep Mountain-Across the Turkish Armenian Divide” and “Book of the Edge”. She has been a journalist since 1993 and has been writing political columns since 2000. Her articles have been published in New Left Review, Le Monde Diplomatique, Global Voices Advocacy and the Guardian.

http://www.indexoncensorship.org/2012/01/turkey-press-freedom-ece-temelkuran/