Written by Joseph Schechla

Written by Joseph Schechla

Much has been written, forgotten and written again over the past century on the subject of Zionism and Israel’s unique civil status categories and corresponding practices. For a person with a long life and memory, it may be surprising to find that the crucial distinction between nationality and citizenship in Israel is news to so many people concerned with the conflict and problem of Zionism. Understandably for observers not regularly engaged in the conflict, such as human rights treaty body members, the concept has been a revelation.1

Why is this fundamental distinction, with its corresponding terminology, a new frontier for others, including many Palestinians long disadvantaged by the institutionalization and material consequences of that very distinction in practice?

A partial answer may lie in the nature and history of anti-Zionism outside Palestine, which has experienced waves and currents since Jewish nationalism first sprang from its eugenic “primordial soup” in race-obsessed fin-de-siècle Europe.2 The Zionist notion that people of Jewish faith constituted a “race” offended emancipationist Jews first and foremost then. That quintessential premise of Zionist ideology and its colonial movement reverted to a presumed, albeit long-discredited, theory that was popular with Jew haters. They and other racists have always sought, conceptually at first, to assert a convincing distinction of the denigrated group so as to socialize the notion that they (the inferior lot) are not like us (self-acclaimed superior beings). The most ambitious racists have tried to invoke scientific – even genetic – criteria for their arguments.

Monumental thinkers and activists, including the Jewish emancipationist Moses Mendelssohn (1729–86), had already struggled intensely to rid Europeans of Jewish faith – and their neighbors – of the convenient falsehood that practitioners of Judaism formed a single, alien bloodline. Such intellectual contributions to debunking that racist notion include a long pedigree of biblical scholars, from Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918), who influenced Hebrew Union College President Rabbi Nelson Glueck (1900–71), who, in turn, mentored Rabbi Elmer Berger (1908–96), who later became the American Council for Judaism’s unwaveringly anti-Zionist executive director.

Advocates of the emancipation of Jews as equal citizens living in democracy – a condition distinct and apart from assimilation3 – also include such notable figures as Berr Isaac Berr (1744–1828), Heinrich Heine (1797–1856), Johann Jacoby (1805–77), Gabriel Riesser (1806–63), and Lionel Nathan Rothschild (1808–79), who drew much of their philosophical inspiration from, and indeed were part of European Enlightenment. As Berger explains, the emancipationist tradition descending from Mendelssohn’s intellectual line sought not only to be free from anti-Semitism, whose proponents sought to characterize people of Jewish faith as a separate “race,” but also from the oppressive Jewish community leadership, exemplified by the stifling authoritarianism and ritualistic religiosity of the shtetl.4

The emancipationist and, at once, anti-Zionist wave in North America drew on this liberal tradition to oppose the Zionist institutions, which embodied much of what the emancipationists in the “Old World” struggled against for centuries, especially the conflation of the Jewish faith with “race.” That Jewish emancipationist wave crested in the late 1960s, as Zionist myths and the power of Zionist institutions dwarfed the American Council for Judaism, the Reform Movement’s most important organized emancipationist anti-Zionist force. The Council was reduced to a mere shadow of its former self, and the affiliated senior advocates of anti-Zionism in that period, including Rabbi Henry Cohen (1863–1952), Judah Magnes (1877–1948), Rabbi Louis Wolsey (1877–1953), Rabbi Abraham Cronbach (1882–1965), Rabbi Morris Lazaron (1888–1979), Lessing J. Rosenwald (1891–1979), Moshe Menuhin (1893–1983) and Rabbi Elmer Berger, alas, have all passed away.

At least a generation now has intervened since most of these anti-Zionist advocates deceased, and two generations have lapsed since the decline of the American Council for Judaism. While some of that history and its continuity are accessible on the current Council’s website,5 the enduring and most commonly identifiable Jewish anti-Zionist positions arise from either the Marxist or Orthodox traditions. The recent book by Shlomo Sand that exposes the constructed myth of a “Jewish people/nation”6 makes no reference to predecessor Elmer Berger, despite his prolific writing on the subject for half of the 20th Century.7

Benefiting from the arguments of the emancipationist tradition, we can better understand the problem they found with the concept of a “Jewish race,” a “Jewish people” and/or, especially, “Jewish nationality.” The institutionalization of this concept, with its grave material consequences for the indigenous people under Israeli rule, reveals how the “Jewish race/people/nationality” concept violates a bundle of human rights of the Palestinian people. In the prophetic writing of Elmer Berger, for example, empowering and funding institutions set up to implement this constructed distinction can only be harmful to Jews and impede – even reverse – their emancipation in democratic countries. However, applied in a country of mixed population and in the context of colonization, where those Zionist institutions operate to privilege people “of Jewish race or descendancy,” it would also predictably harm the “non-Jewish” population.

And so it has come to pass.

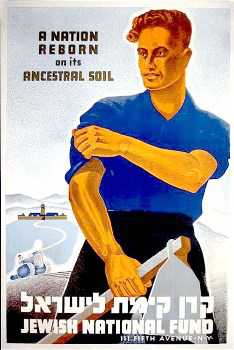

It Harms Jews

As the Jewish emancipationists teach us, “Jewish nationality” is a concept arising from Zionist ideology that has become enshrined in the charters of the principal Zionist institutions engaged in colonizing Palestine since the end of the 19th Century (World Zionist Organization/Jewish Agency8 and Jewish National Fund9). Thus, even before the Zionist colonization project found resources and other means to colonize Palestine, the very codification of such a racialist concept, particularly by institutions populated and affiliated with Jews, could not have been more objectionable.

It Promotes a Racist Classification of Jews

For Jewish emancipationists, for centuries advocating common citizenship and nondiscrimination guaranteed by the democratic state, the notion of a “Jewish race,” as such, undermines the pursuit of equal status for all people of Jewish faith, or of any creed or color. Zionism creates an unwanted barrier between them and their neighbors. The creation of a race identity for Jews encourages stereotyping and seeks to provide a scientific basis for discrimination. While this concerned the emancipationist Jew directly, the promotion of a “Jewish race” also runs counter to more general efforts to combat the ideological falsehood of racism.

In fact, humans are far more genetically similar than other species. They are all homo sapien sapiens, without subspecies. Any superficial differences manifest as a result of three possible processes: random mutations, natural adaptations to climate and environment, and personal selection. The last of these involves the physical mixing of new genetic material through procreation by otherwise distant partners brought together by choice, travel, migration, conquest or trade.

The use of “race” as a means of justifying the exploitation of a human group or groups by others is inherently immoral. Such racism has been condemned by scientists, law makers and diplomats at the international level. A UNESCO statement following World War II, The Race Question, reflects the collaboration of leading natural and social scientists commonly rejecting race theories and a morally condemning racism.10 That consensus statement suggested, in particular, to “drop the term ‘race’ altogether and speak of ‘ethnic groups.’”11 In the post-Nazi era, “Jewish race” is an anachronism.

It Claims to Act on Behalf of All Jews

The concept of “Jewish race” incorporated in the charters of the Zionist institutions, thus, became coupled with the Zionist political program. The objective of colonizing Palestine to create a “Jewish national home” implied that such an enterprise was being carried out in the name of, and on the behalf of all people of Jewish faith. The Jewish objection to such a generalization was grounded in the value and fact of free will among individual Jews, regardless of the individual’s position on the colonization of Palestine. Open inquiry and debate has been a time-honored Jewish methodological tradition. The Zionist cry for all Jews to rally to the colonial project on the basis of an involuntary and immutable affiliation to a “Jewish race” was seen as alien and antidemocratic on its face. The conformism required by Zionist leaders, theories and institutions led to eventual bullying tactics against non-compliant Jews.12 For those with a deeper historical memory, that invoked life in the shtetl, from which so many sought to one day be free.

Israel’s Basic Law: Law of Return (1950), while defining a nationality right of “return” (aliyah)13 reserved for Jews only, provides a definition of belonging to this category of persons – including citizens of Israel, or of other countries – as members of the Jewish “race” promoted in the Jewish National Fund (JNF) charter. The Law of Return specifies, for the purpose of that Law, that “‘Jew’ means a person who was born of a Jewish mother or has become converted to Judaism and who is not a member of another religion.”14

Both Zionist leaders and institutions, as well as Israeli politicians, have interpreted support for practical Zionism (replacing the indigenous people of Palestine) variously as a “Jewish” obligation, and/or as an act of survival, self-preservation and even “national liberation” for Jews.15 Any specter of Jewish persecution potentially helps to make this Zionist argument convincing.

Along with the concept of belonging to the Zionist project to colonize Palestine by virtue of some biological imperative also came the insistence that a “good Jew,” a “good Zionist,” should live in Israel, or at least support the Zionist project from other countries, if necessary. In the minimum, this could be accomplished by Jewish children everywhere dropping coins into JNF blue boxes to contribute to the colonization effort.

In the legal dimension, Israel’s World Zionist Organization–Jewish Agency (Status) Law (1952), whose importance is discussed below, specifies that Israel is the state of the “Jewish people” and provides:

The mission of gathering in the exiles, which is the central task of the State of Israel and the Zionist Movement in our days, requires constant efforts by the Jewish people in the Diaspora; the State of Israel, therefore, expects the cooperation of all Jews, as individuals and groups, in building up the State and assisting the immigration to it of the masses of the people, and regards the unity of all sections of Jewry as necessary for this purpose

It Imposes a Foreign “Nationality” on Jews

A practical feature of “Jewish nationality” is that Israel and its “national” (para-state) institutions, including the World Zionist Organization/Jewish Agency (WZO/JA) and Jewish National Fund (JNF), apply this charter-based status to Jews living in many countries around the word. These institutions extend the Jewish “obligation” to support Zionism practically and financially, whereas the State of Israel is precluded, as is any foreign state, from interfering in the status of any citizen in a country outside its internationally defined state jurisdiction. The Zionist institutions, as Israeli state agents, nonetheless operate overseas programs to engage and recruit Jews in their own countries of citizenship to carry out “practical Zionism.”16

In the 1960s, Reform Jews in the United States objected to the Zionists’ imposition of an unwanted second “nationality” and foreign state affiliation imposed by the WZO/JA. At their request, the U.S. Department of State issued a legal opinion in response to this unique case of foreign state intervention in the status of U.S. citizens. The legal position affirmed that the United States “does not regard [Israel’s extraterritorial] ‘Jewish people’ concept as a concept of international law.”17 The related legal battle led to the Superior Court of the District of Columbia forcing the U.S. Justice Department to register WZO/JA as foreign agents, instead of the tax-exempt charity status that they claimed to themselves.

Since 1791, with the recognition of Jews as French citizens equal to other citizens in all rights and obligations, emancipation became the norm across Europe and the wider world. Israeli para-state institutions imposing “Jewish nationality” and promoting corresponding obligations on citizens of some fifty other countries where those institutions operate may be seen as threatening to undo over three hundred years of progress in the struggle for equal status of the Jew as citizen in a democracy. The concept of “Jewish nationality,” or belonging to a “Jewish nation” (le’om yahudi) also gives credence to the old anti-Semitic charge that Jews are disloyal to the countries in which they live. In this light, the “Jewish race/nationality” concept makes Jews outside Israel vulnerable to reprisal and charged of alien status. Moreover, these breaches of international legal norms on nationality vitiate the rights of other sovereign states by inciting their Jewish citizens to emigrate and pledge allegiance to a foreign country (Israel) and extending an additional alien civil status to them by claiming them as subjects under the legal jurisdiction of Israel.

Also for Jews in Israel, the “national” institutions and corresponding legislation apply “Jewish nationality” to create irreconcilable distinctions in civil status with others living in the “Jewish state.” With unique privileges applying to “Jewish nationality” (le’om yahudi) that are denied to holders of mere Israeli “citizenship” (ezrahut), no one in Israel has the prospect of living in a state possessing the fundamental features of a democracy. A famous Israeli High Court case in 1971 affirmed that “there is no Israeli nation separate from the Jewish nation…composed not only of those residing in Israel but also of Diaspora Jewry.”18 The President of the Court Justice Shimon Agranat explained that acknowledging a uniform Israeli nationality “would negate the very foundation upon which the State of Israel was formed.” Thus, for a Jew to reside in Israel is to negate the essential values of the emancipationist tradition, regardless of one’s position on the colonization project.

It Harms Palestinians

To interpret an Israeli law, or any Zionist document, it is necessary to know Zionist terms and their ideological meaning. While the “Jewish people” concept is essential to Zionist public law relations with Jews outside of the State of Israel, the Israel Government Year-Book (1953–54) recognized the “great constitutional importance” of the Status Law (1952): Not only did Israel’s first prime minister submit it for legislation as “one of the foremost basic laws,” but also clarified that “this Law completes the Law of Return in determining the Zionist character of the State of Israel.”19 The cornerstone of the discriminatory legal structure is the Status Law (1952), supported by two Basic Laws: the Law of Citizenship and the Law of Return.

Israel’s Basic Law: Law of Return (1950) effectively establishes a “nationality” right for Jews only. Under the Law of Return,20 only Jews are allowed to come to areas controlled by the (civilian or military) Government of Israel to claim the “super-citizenship” status of “Jewish nationality” [le’om yahudi], while acquiring their new civil status in Israel through “return.” This notion of a “Jewish national” who “returns” for the first time from some other domicile country to Palestine is majestically ideological and wholly unique, even among other colonial-settler states.

The criteria for acquiring citizenship under Israel’s “Citizenship Law,” amending Section 3A in 1980,21 disqualify the majority of Palestinian families who fled from their homes in the 1948 ethnic cleansing, effectively blocking their rightful status as citizens – and nationals – in their own country, where Israel is the de facto successor state. Thus, the title of the “Law of Return” is bitterly ironic, as it allows for the “return” of individuals who never lived in Israel before, and – supported by other legislation – prevents the actual return of people who had been residents in the land.

Already in January 1949, the new Government of Israel signed over one million dunams of Palestinian land acquired during the war to the parastatal JNF to be held in perpetuity for “the Jewish people.” In October 1950, the state similarly transferred another 1.2 million dunams to the JNF.22 In 1951, a JNF spokesman explained how, necessarily, JNF “will redeem the lands and will turn them over to the Jewish people—to the people and not the state, which in the current composition of population cannot be an adequate guarantor of Jewish ownership.”23

In September 1953, the Israeli Custodian of Absentee Properties executed a contract with the Israeli Development Authority, transferring the “ownership” of all the Palestinian refugee lands under his control to the latter. The price (not value) of these properties was to be retained by the Development Authority as a loan. At the same time, the Custodian conveyed the ownership of the houses and commercial buildings in the cities to Amidar, a quasi-public Israeli company founded to place Jewish settler/immigrants.24 Thus began a practice that forms and unbroken pattern of continuing dispossession to this day.

Three months before that 1953 transaction, the Jewish National Fund also executed a contract with the Development Authority, whereby the Authority sold 2,373,677 dunams of “state land” and lands held by the Authority to the Jewish National Fund. The JNF completed the deal just after the Authority concluded its transaction with the Custodian. As a result, this Palestinian property came under the possession of the JNF, which claimed to own over 90% of the total territories that fell under the control of the state of Israel. These properties are referred to as “national land,” a subtle but important distinction, meaning that it be limited to exclusive use by (Jewish) “nationals,” whoever and wherever they may be, and foreclosed to the indigenous people, whoever and wherever they may be, including the actual private and collective owners.25

To understand how “Jewish nationality” operates in practice to discriminate against non-Jewish “citizens” of Israel, especially the indigenous Palestinian ones, one must appreciate that the Zionist para-state institutions that authored the concept and enshrined it in their charters, are also the same guardians of “Jewish nationality” privilege. This is particularly institutionalized in economic fields, most clearly activities involving land, housing, public services and development.

Israeli laws related to these fields of human activity, and even many aspects of commerce, give special policy and implementation status to the WZO/JNF and/or JA; that is, by applying those institutions’ chartered principle of benefiting exclusively persons of “Jewish race or descendency.” For Jews in Israel, the emancipationist dream of living free in a democratic society is shattered and, so far, unregenerate.

Many of the current stories of deprivation of the Palestinian people derive from the institutionalized application of this concept of “Jewish race/people/nationality.” The plight of the Palestinian refugees, the analogous case of the internally displaced persons since 1948, the continuum of land confiscation inside 1948-incorporated territories, the nonrecognition and poverty of the Naqab Bedouin villages and other contemporary human rights violations involve application of a superior “Jewish nationality” status at the expense of Israeli “citizens.” Worse affected are those other indigenous people who, as refugees, are unable to enter their country. The damages, costs and losses to the indigenous Palestinian people are material consequences of the Zionist ideological and institutional system by default as well as by design.

Conclusion

The emerging literature related to the question of “nationality” and “citizenship” in Israel generally acknowledges the distinction between the two types of civil status. However, that analysis does not always apply the normative framework of international public law and social justice, codified in human rights standards. Instead, the explanations are more likely prefaced with the assumptions of Zionist ideology, derived from longing to be separate, if not to be free.26

In the light of the ground-breaking work of post-Zionist historians, and the recent work of Ilan Pappé and Shlomo Sand, now may be the time to rediscover also the earlier generation of emancipationist, anti-Zionist commentators who addressed the hazards of “Jewish race/people/nationality” and the operations of their mother institutions generations before us. These Zionist concepts and their implementation afflict both people of Jewish faith and Palestinians victims everywhere. Implementing “Jewish nationality” extraterritorially also affects the rights of states and citizens in other countries where the Zionist para-state institutions operate. In that sense, at least, besides our sharing one species, we are all related.

Endnotes

————-

. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), Concluding Observations: Israel, E/C.12/1/Add.27, 4 December 1998, paras. 11 and 35; CESCR Concluding Observations: Israel, E/C.12/1/Add.90, 23 May 2003, p. 18; “Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination: Israel, CERD/C/ISR/CO/13, 14 June 2007, paras. 15–23.

. Melanie A. Murphy, Max Nordau’s Fin-de-Siècle Romance of Race (New York: Peter Lang, 2007).

. As explained in Elmer Berger, The Jewish Dilemma (New York: Devin-Adair, 1945).

. Elmer Berger, A Partisan History of Judaism (New York: Devin-Adair, 1951), pp. 79–97.

. Access the American Council for Judaism website at: http://www.acjna.org/acjna/default.aspx. See also Thomas A. Kolsky, Jews against Zionism: The American Council for Judaism, 1942–1948 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990).