Turks look to mobile technology to change bazaar cash customs

The Observer, Sunday 20 November 2011

Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar

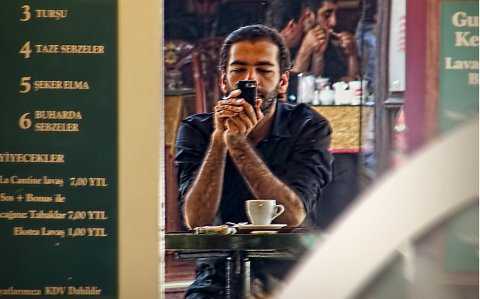

Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar where, for the moment, cash is still king. Photograph: Kerem Uzel/Narphotos

In Istanbul’s grand bazaar you can smell the money changing hands as tourists go into battle over carpets and fake designer handbags. Cash is king here – haggling prowess sets the price, rather than the beep of a barcode scanner. But that could be about to change, as young Turks embrace technology that could consign banknotes and tense verbal exchanges to the dustbin of history.

The explosion in mobile phone use is changing the way Brits consume, but in Turkey, where half of the estimated 79 million citizens are under 30, it is offering new vistas to a rapidly urbanising population. This powerful demographic has encouraged banks and telecoms companies to choose Turkey as the test bed for the latest mobile payment systems, which essentially turn a phone into an extension of your wallet. Some 62 million Turks own a mobile phone, a startling statistic given that an estimated 40% do not have a bank account.

“With mobile banking, the world has split into two: in developing countries the mobile network often has a greater reach than the banking system and can fill in the gaps,” says Paul Lee, telecoms research director at Deloitte. “Technology is empowering, and this is one way of getting money flowing.”

The crowds of shoppers – all with mobiles clamped to their ears – in the fashion stores on Istiklal, Istanbul’s cosmopolitan shopping street, point to rising living standards. Per capita income is up from $4,200 in 2000 to $10,000 (£6,336) last year.

“Sometimes you see people talking on two phones at once,” says Mete Güney of MasterCard. “And many people who don’t have a bank account do have a mobile phone.”

As in other countries, he adds, the young love technology, but many are outside the banking system because of their age or lack of financial education. MasterCard’s network provides a secure backbone for mobile payments.

In Galatasaray’s new home ground, the TT Arena, football fans can use “digital” rather than hard cash to pay for their kofte ekmek (meatball rolls) at half time. But the technology has more serious applications in countries where large numbers of people have moved away from rural areas and need to send money back home.

This year Turkcell, the country’s biggest mobile phone operator, launched a prepaid card that can be registered on a mobile and used to pay for goods or send money – even where neither party has a bank account. The recipient uses a code to withdraw the cash from an ATM. More than 100,000 of the cards were sold in the first four months.

“These people may never have been to a bank, but they come to our store at least once a month to top up their phones,” says Turkcell’s Cenk Bayrakdar. “For people who can’t get credit cards it feels like a credit card.”

Silhouettes of cranes and half-built apartment blocks now rival Istanbul’s famous mosques on the city’s night skyline, and are the physical evidence of an economy that has grown at an average of 4.4% for the past decade. But Mert Yildiz of Renaissance Capital points out that Turkey’s current account deficit, at 10% of GDP, is one of the biggest in the world and that a huge shadow economy represents possibly a third of GDP. Some 40% of Turks do not report any income.

He also has a problem with the Civets tag , which he says bands together a bunch of countries that have nothing to do with each other: “Turkey’s economy can grow 7% one year and contract 7% another.”

Unemployment of around 10% is a structural issue for Turkey, as businesses struggle to absorb the 900,000 young adults who enter the workforce each year. Also, Yildiz says, soaring property prices point to a credit bubble, and although incomes are rising, distribution is increasingly unequal. “Better-educated young people are feeling better off, but in the suburbs and rural areas the picture is different.”

Garanti, the country’s second-largest private bank, says its target is for Turkey to become a “cashless utopia” by 2023. This is in keeping with other ambitious goals for the republic’s centenary year and would force a formalisation of the underground economy.

“The challenge for Turkey is to get more customers into banking,” says Garanti’s Mehmet Sezgin. Its new contactless credit card is called Trink (the name is supposed to remind Turks of the tinkle of small change) and the chip can be embedded in a mobile sim card or even a digital watch – although Garanti could not convince Swatch to make them.

“We don’t have coin purses,” Sezgin says. (Decades of runaway inflation rendered Turkish coins irrelevant long ago.) And Turks never had cheque books, so personal banking “skipped a step” on the way to e-banking.

Sezgin says 2m of the 600m card transactions the bank will process this year will be contactless, but expects that to jump to 18m in 2012: “We believe cash can be taken out of the equation if the technology can be consumed right,” he says. “Smartphones, tablets … all the time new technology is coming to market.” But will they ever take to it back at Istanbul’s famous market? “If my utopia is achieved, even in the grand bazaar they should only accept cards of one form or another,” says Sezgin. “I am an optimist.”

via Turks look to mobile technology to change bazaar cash customs | Business | The Observer.