Is this the Summer of Censorship? In the US, it emerged that the NBC network requested a film trailer remove the word “abortion” in order to be advertised on its website. From New York to Tel Aviv, there are calls to scrap the Metropolitan Opera’s production of “The Death of Klinghoffer”, lest it “inflame anti-Semitism”. Here in Britain, we’re being urged to ban junk food advertising full-stop, the same week as the “Right To Be Forgotten” came into force, which allows those wealthy and clued-up enough to sue internet search engines into removing information they find embarrassing from search results, however accurate that information may be. So major newspapers are being informed their content will not be displayed on Google, but in the interests of privacy, they can’t be informed why, or who requested the block. It’s a misnomer, another instance of what I’ve called our chronic addiction to the language of rights. Hear a mention of a “right to be forgotten” on the radio, and who could possibly object? Rephrase it as “the right to forget Robert Peston’s exposure of the financial crisis”, or as Mark Stephens calls it, “the right to burn the index cards in a library of record”, and it suddenly sounds a lot more sinister.

But the biggest censorship row brewing is one of our oldest. A few years ago, I struck up a conversation with a jovial bookseller in Istanbul. We were talking in German, which was quicker for him than English, and closer to the realms of possibility for me than Turkish. Having established, therefore, my interest in Germany, his eyes lit up. “Ah! I have a real secret for you. It’s banned in Germany, you know. The Jews won’t let you read it.” And as I bristled in doorway, uncertain whether how safely I would walk the streets of Cağaloğlu if I confronted him on his own turf, my formerly charming companion pressed into my hands a shiny, newly published copy of Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

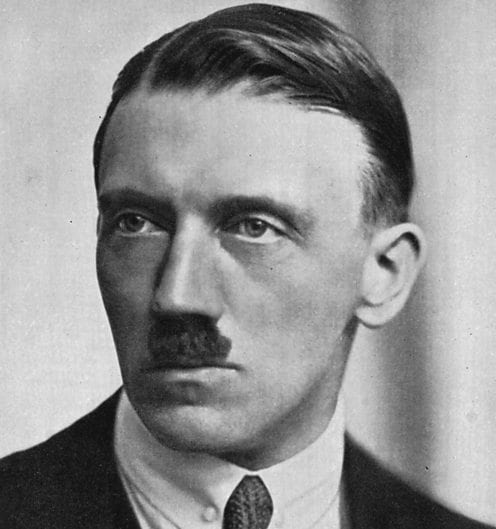

I thought of my Turkish encounter this week, as it emerged that the Interior Ministers of the 16 German Länder have just agreed to do their utmost to continue the legal injunctions on publications of Mein Kampf in Germany after copyright expires on the first day of 2016. Currently, the state of Bavaria owns the literary estate of Adolf Hitler, and limits publication in Germany to a few excerpts for official history textbooks. As Sally McGrane reports in The New Yorker, the state has even withdrawn support for an academic edition which plans to publish the text with heavily critical annotations. For example, the passage in which Hitler complains about the treatment of First World War veterans will be accompanied by a reminder that his own regime would later gas 5,000 shell-shocked veterans of that war under his euthanasia plan. But even this official history is an allowance too far for the Bavarian state, which withdrew its authorisation last December (though it gave up on reclaiming its money). The highly respected Institute for Contemporary History is pressing ahead with the project nonetheless, and hopes that it will be able to publish after the copyright expires in 2016 – but the ongoing legal battles which inspired this week’s announcement may yet see the Institute’s years of academic study buried.

Berlin’s caginess over the issue is understandable – Hitler’s legacy remains acutely sensitive in Germany, and in a nation which once centrally instituted state power to enact the most totalitarian of brutalities, the libertarian position of absolving the nation state any ongoing cultural responsibility chafes against a collective memory. To be more cynical, no politician wants to be the minister who brought back Mein Kampf. And as McGrane’s report makes clear, Germany is haunted by the image of “Neo-Nazis handing out the book in school yards”.

But if there’s a danger of Mein Kampf flooding school libraries, it’s not in Germany. In Turkey, where Israel remains the local villain, the book is a best seller. And when I remember my friendly bookseller in Istanbul, I remember how sure he was that the ban would be the book’s unique selling point, his absolute conviction that censorship implied conspiracy. The publication of Mein Kampf may well be a traumatic moment for Germany internally. But as a leading player on the global stage, it also has an international responsibility. Germany’s leaders need to think about how the Mein Kampf ban affects the Middle East, and what it says about the West’s values of free speech, at a time when we are constantly forced to defend ourselves against accusations of hypocrisy. I think I may explode if I hear one more activist claim that the West, collectively, discriminates against Islam, because we decline to ban blasphemy against the Prophet, while Germany maintains its bans against Holocaust Denial or publishing Mein Kampf. This is the self-pity of the oppressor, demands for special treatment dressed up as victimhood. Germany’s bans around Holocaust material are the exception in the West’s approach to freedom of speech, not the rule. But they are a dangerous exception, undermining any claim that Western civilisation promotes an equal playing field of ideas.

Mein Kampf is, of course, unreadable. Seven hundred pages long in the official Nazi edition, it reminds me above all of the screed spewed out by Elliot Rodger, the mentally ill misogynist killer from California. It’s as ragefully biographical – what McGrane generously calls “bildungsroman style”, and what nowadays would be a little-read livejournal entry – with chapters called “In the House of my Parents” and “Years of Study and Suffering in Vienna”. If Hitler were female, he’d have included a chapter called “My Bitter First Period”. But even were Hitler’s prose peerless, it would remain important for us to engage with dangerous ideas. That’s why I was horrified to learn earlier this term that at my own university, UCL, the student union had taken it upon itself to ban a “Nietzsche Society”, in so far as a pompous union has the power to do so. (Their published statement on the matter emphasises the union’s dedication to “fighting the root cause of fascism — capitalism”, which is the Closing of the British Mind in a neat nutshell. I thought their job was to help students support themselves). When I was an undergraduate, I encountered Nietzsche seriously for the first time – and sure enough, I felt an odd thrill at finally hearing an intellectual explanation of a philosopher’s name which had always evoked taboo. But there’s nothing like spending hours jawing with purist 21-year-olds about every possible translation of die ewige Wiederkehr to wean one away from fascism. Perhaps, if Germany really wants to neutralize the dangers of Mein Kampf, it needs to institute a new set of punishments in schools. Force your kids to write out lines of Hitler’s verbiage in detention, and there’s no way they’ll waste lunch breaks passing it round the playground.

• Get the latest comment and analysis from the Telegraph