Turkey Is Drawn into Iraqi Affairs

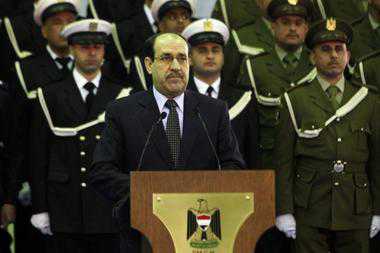

In the wake of the withdrawal of US forces, Maliki has moved to consolidate his power, threatening to undermine the delicate balance between various sectarian and ethnic groups. Maliki, who assumed his current post following a 2010 power sharing agreement, has failed to work toward national reconciliation. On the contrary, in this already fractured country, he has even undermined the governing coalition and also put Iraq on a collision course. His campaign against Vice President Tariq al-Hashimi, who took refuge in Northern Iraq fearing for his life, crystallized the power struggle. The dispute grew into an impasse, with the increasingly harsher tone of the parties, engulfing Turkey (EDM, January 18). After spending some time in Kurdistan, Hashemi visited Saudi Arabia and Doha and later came to Turkey, effectively beginning his days in “exile.” Calling openly for Ankara’s support, Hashimi also furthered its involvement in his country’s affairs (Anadolu Ajansi, April 10).

A parallel process concerned Iraqi Kurds. The KRG’s relationship to Baghdad is complicated over the status of the disputed city of Kirkuk and the conflict over revenues from the exploration of natural resources in the North. In the ongoing standoff, the leader of KRG, Masoud Barzani, supports Hashimi and has used the leverage he gained to further bolster his position in Iraqi domestic politics. Last month, Barzani suggested he could hold a referendum to redefine ties to Baghdad. In a move that further accentuated this trend, during his trip to the US earlier this month, Barzani urged Washington to reconsider its backing of Maliki. Then, Barzani visited Turkey to meet with Hashimi and Turkish leaders (Anadolu Ajansi, April 20).

Barzani’s visit also underscored the degree to which Turkey has readjusted its regional policies. After years of confrontation with the KRG, Turkey already moved to normalize its relations with the Northern Iraqi Kurdish leadership to solicit their backing for Ankara’s fight against the PKK. In the wake of the latest developments, Ankara has further moved toward Iraqi Kurds to cope with the challenges in Iraqi domestic politics.

In the region, too, Turkey faces a similar fluid environment. With the unfolding of the Syrian uprising, Ankara’s partnerships in the region have gone through a new reshuffling. Faced with Tehran’s support for the Syrian regime and its backing of Iraq’s Maliki, Turkey’s coordination of its policies with the Syrian opposition, Iraqi opposition and the Gulf countries raise interesting questions about the patterns of Ankara’s alignment.

These realignments lead some to suggest that Turkey has been drawn into sectarian groupings but the Turkish government rejects those claims. Ankara justified its support for the Syrian opposition on the principles of human rights and democracy, rather than any sectarian affiliation. In Iraq, Turkey again refrained from framing its support for the Sunni leader Hashimi in sectarian terms and instead underlined the divisive nature of Maliki’s policies.

However, such statements from Turkish officials have far from convinced the Iraqi leadership. Maliki, already critical of Turkey’s policy on Syria, reacted harshly to recent developments and, in a press release, accused Turkey of interfering in Iraqi internal affairs and acting in a hostile manner (Milliyet, April 21). Reflecting the new regional realignment, Maliki then paid a two-day visit to Tehran on April 22-23, where he met with key Iranian leaders. In his first visit after his reelection, Maliki expressed solidarity with the Iranian leadership and vowed to work in tandem on regional issues (www.presstv.ir, April 23).

Both Prime Minister Recep Tayip Erdogan and Turkey’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs gave a very strong reaction to Maliki’s remarks. On his way back from Doha, where he discussed Middle East issues with his regional counterparts, Erdogan called Maliki insincere and maintained that his oppressive policies threatened to divide Iraq. Suggesting that Maliki himself might have a sectarian agenda, Erdogan insisted that Ankara was in communication with all Iraqi groups including Shiite leaders (Sabah, April 22). The MFA’s statement also referred to Maliki’s attempts to monopolize power and exclude others as the basis of the current crisis in Iraq (www.mfa.gov.tr, April 21). Both countries summoned each other’s diplomats posted to the respective capitals over the developments.

To Turkey’s credit, concerns over Maliki’s course are indeed shared by a larger number of Iraqi actors, including Shiite groups. Increasingly, the inability of Maliki to build up coalitions with other groups and the weakening of the ties between Baghdad and the provinces, most notably Northern Iraq, are criticized by major Iraqi actors. Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr also visited Northern Iraq for the first time, in an effort to establish bridges between the parties (Anadolu Ajansi, April 26).

For years, Turkey has worked to ensure a smooth political transition in Iraq. Ankara’s policy was based on the understanding that if national reconciliation cannot be achieved, it could deepen the fragmentation and pave the way for an independent Kurdish state, not to mention other damaging repercussions for regional peace. It was for this reason that Ankara supported the Maliki-led government, although its initial preferences after the Iraqi elections had been different. With the ongoing political crisis and tensions in the region, Turkey has increasingly found itself on the same page as the KRG.

For his part, Barzani apparently hopes to deepen his cooperation with Turkey to further consolidate his position in Iraq. This development inevitably raises speculations as to whether the Iraqi Kurds might press for independence or a greater degree of autonomy from Baghdad, which, ironically, will put Turkey in a difficult position. Given Ankara’s own concerns about an independent Kurdish state and the Kurds’ claims over Kirkuk, Turkey’s support for Barzani will be conditional and it will hardly be the midwife to an independent Kurdistan.