By Soner Cagaptay, Special to CNN

Editor’s note: Soner Cagaptay is the Beyer Family fellow and director of the Turkish Research Program at The Washington Institute. His publications include the forthcoming book ‘Turkey Rising: The 21st Century’s First Muslim Power.’ The views expressed are his own.

Turkey’s Syria policy now seems to have one goal: take down the al-Assad regime. With this in mind, Ankara has become actively involved in the Syrian uprising, supporting the opposition and allegedly allowing weapons to flow into Syria to help oust Bashar al-Assad. But not everyone vying for power in post-al-Assad Syria has welcomed Turkey’s helping hand.

Enter the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), Ankara’s archenemy for decades. The PKK and its Syrian franchise, the Party for Democratic Unity (PYD), which holds sway over the Syrian Kurds, have recently secured parts of northern Syria adjacent to Turkey. This suggests that when the al-Assad regime falls, Turkey will be confronted with PKK and PYD-run enclaves across from its border with Syria.

As hostile as the PKK has been towards Ankara, though, the PKK cannot afford to carry this menacing anti-Turkish attitude into Syria. After al-Assad is gone, the Syrian Kurds represented in the PYD will discover that they are fated to become woefully dependent on Ankara for survival, much like the Iraqi Kurds were after the end of the Saddam regime in Iraq.

Simple geography dictates this. The PYD holds sway among the Syrian Kurds in the northwestern part of that country. These Kurdish-dominated areas are non-contiguous enclaves, surrounded by Arab majority areas with Turkey to the north. One emerging battle in Syria is conflict between Arabs and Kurds. When that struggle fully unfolds, the Kurds in northwestern Syria will have no friend but Turkey to rely on as leverage against that country’s majority Arabs. This will present the PKK in Syria with a stark choice: fight both Turkey and the Arabs on all four sides and perish, or rely on Turkey to increase their bargaining power vis-à-vis the country’s Arab majority. Survival will require the second path, and as surreal as it sounds now, the PKK’s Syrian branch will acquiesce to Turkish power.

More from GPS: Why U.S. should rethink Syria Kurds policy

This corresponds to a seismic shift in Turkey’s Kurdish policy. Until recently, Ankara had seen the “Kurdish card” in the region as a threat to its core interests. Now, this appears to be changing. Ankara has reportedly built intimate commercial and political ties with the Iraqi Kurds. Now, Ankara wants something similar with the Syrian Kurds. If the PKK in Syria is deft enough to curry favor with Ankara, Ankara will return the favor.

The Turkish Kurds are the last piece of the puzzle. If recently announced peace talks between the Ankara government and jailed PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan succeed, Turkey may be able to turn the “Kurdish card” to its favor.

If the peace talks go as planned, PKK members will lay down their weapons. In return, Turkey would issue a blanket amnesty to the group’s core membership currently located at the Kandil enclave in northern Iraq, and possibly grant some cultural rights to its Kurdish population. And Ocalan, who has been in solitary confinement in an island jail, will see an end to his isolation.

Still, the Syrian Kurds in the PKK’s Kandil enclave in mountainous northern Iraq could spoil this process. Many among the PKK’s membership, especially those from Turkey, will listen to Ocalan. But some hardline leaders could refuse to buy into what they might perceive as a personal deal to set himself free.

All this means that while the PKK in Syria will moderate its behavior towards Turkey because it has to, the Syrian Kurds in the PKK will likely maintain a hardline stance against Ankara.

Turkey may be able to preempt such a scenario by showing the Kurds in Syria a degree of friendship that exceeds even the outreach it has shown to the Iraqi Kurds. Such a strategy might help placate the animosity of the Syrian Kurds in Kandil towards Ankara, though it will not fix the problem.

For now, it appears that while the PKK in Syria will not bite Turkey, Syrian Kurds in the Kandil enclave will remain the biggest hurdle to Turkey being able to claim the Kurdish card for itself.

Post by: CNN’s Jason Miks

via Can Turkey seize the ‘Kurdish card’ for itself? – Global Public Square – CNN.com Blogs.

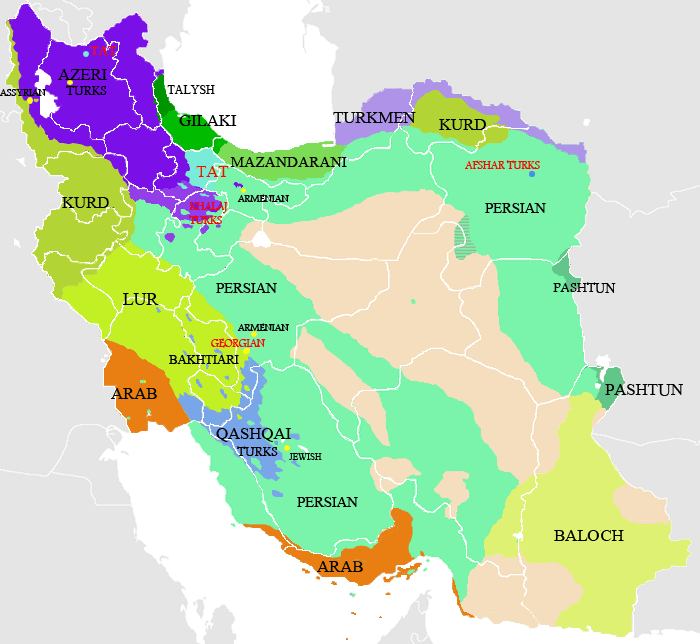

Iran has always presented a thorn in the eye of Western policy makers since the Pahlavi dynasty and its resurgent nationalism. Being strategically located in a position that affords it to patrol and play a significant part in monitoring and controlling the flux of forty percent of the world’s oil flows, the foreign policies of superpower governments teetered between soliciting Iranian support and stability through backing and the focused undermining of Iranian regional power. Throughout modern history, we have seen both policy aims carried out with effect. The crux of the issue is Iran’s power to blockade the Strait of Hormuz and its military capability to do so. Looming over this immediate outcome is Iran’s power as a multiethnic nation state with vast oil, mineral, and gas resources. Its large coastline with the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea also affords it power that it is able to project within the spheres of the Gulf States, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. One of the aims of Iran’s nuclear program is to solidify its hold on regional power and prevent any foreign intrigue from upsetting this influence.

Iran has always presented a thorn in the eye of Western policy makers since the Pahlavi dynasty and its resurgent nationalism. Being strategically located in a position that affords it to patrol and play a significant part in monitoring and controlling the flux of forty percent of the world’s oil flows, the foreign policies of superpower governments teetered between soliciting Iranian support and stability through backing and the focused undermining of Iranian regional power. Throughout modern history, we have seen both policy aims carried out with effect. The crux of the issue is Iran’s power to blockade the Strait of Hormuz and its military capability to do so. Looming over this immediate outcome is Iran’s power as a multiethnic nation state with vast oil, mineral, and gas resources. Its large coastline with the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea also affords it power that it is able to project within the spheres of the Gulf States, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. One of the aims of Iran’s nuclear program is to solidify its hold on regional power and prevent any foreign intrigue from upsetting this influence.