Interview with Corry Guttstadt

Turkologist Corry Guttstadt has published a comprehensive study of the behaviour of the Turkish government towards its Jewish citizens during the Holocaust. In doing so, she has investigated a chapter of twentieth-century history that has thus far been all but neglected by international Holocaust research. Sonja Galler spoke to her about her findings

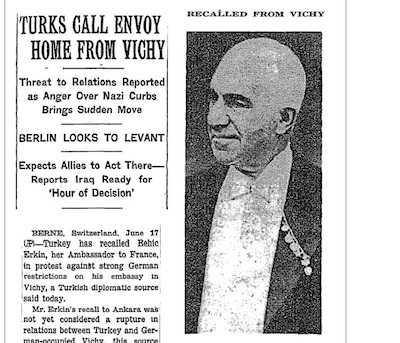

| Bild:

Corry Guttstadt: “Over the course of many centuries, the Ottoman Empire was an immigration destination for Jews fleeing the Reconquista in Spain and pogroms in Eastern Europe. Nevertheless, to portray the Ottoman Empire as a ‘multicultural paradise’ is absurd and ahistorical.” | Much is made of the fact that there are approximately 20,000 Jews in Turkey today, a figure that is frequently held up as evidence of the country’s tolerant attitude towards its Jewish minority. It is often claimed that this success story began when persecuted Sephardic Jews found refuge in the Ottoman Empire, the forerunner of the modern Turkish state …

Corry Guttstadt: Well, there are currently over 20,000 Jews in Iran too. A number alone is not necessarily a reliable indication of whether somewhere is safe or free from anti-Semitism. As far as Turkey is concerned, it is important to emphasise that only 20,000 Jews now live in the country. That’s in stark contrast to the estimated 120,000 to 150,000 that lived in the region at the end of the First World War. Both before and after the Second World War, and most particularly after the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, the vast majority of Jews left Turkey. This was a reversal of the trend of previous centuries.

Over the course of many centuries, the Ottoman Empire was an immigration destination for Jews fleeing the Reconquista in Spain and pogroms in Eastern Europe. Nevertheless, to portray the Ottoman Empire as a “multicultural paradise” is absurd and ahistorical. As non-Muslims, the Jews were subject to countless constraints. Like the Christians, they had to pay a poll tax and were obliged to behave in a submissive manner towards Muslims. Moreover, it must be said that there were numerous fluctuations in the fortunes of the Jews in the 600-year history of the Ottoman Empire.

The period of Jewish persecution on the Iberian peninsula coincided with the expansion of the Empire, whose rulers were keen to increase the urban population. Another reason why they were happy to welcome the Sephardic Jews was because they brought with them important skills and expertise. Jews who had settled in Anatolia and in the Balkans before the Ottoman conquest, on the other hand, were forced to resettle – also for demographic reasons – and were subject to a number of considerable constraints.

What was life like for the Jews around the time the Turkish state was created?

Guttstadt: The foundation of the Turkish Republic in 1923 was the final chapter in the protracted disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, which had lost most of its territory in a series of wars against major Christian European powers. The situation for the Jews varied because unlike the Christian populations in the Balkans, they were not pursuing any separatist goals. In response to European protests about the Armenian massacre, Ottoman leaders liked to point to the Jews as a “model minority”.

| Bild:

Guttstadt reveals that the dissemination of anti-Semitic tracts in the 1930s heralded the birth of modern Anti-Semitism in Turkey | For their part, the Jews were often the target of anti-Semitic attacks at the hands of Christian minorities around this time and were, for that reason, reliant on the protection of the state. Consequently, most Jews initially regarded themselves as allies of the Kemalist movement and looked to the new Republic with largely positive expectations. These hopes were quickly dashed because despite their attempts to adapt and their declarations of loyalty, the Jews quickly became a target for the rigid nationalism of the young Republic. One of the defining policies of the young republic was the “Turkification” of state, economy, and society.

In this light, the Kemalist leadership regarded the rights that had been granted to non-Muslim minorities in the Treaty of Lausanne as a continuation of the interference of major imperialist powers. It put non-Muslim religious communities under pressure to renounce these rights “voluntarily”. Jews were also successively driven out of a number of professions and economic sectors. This prompted many Jews to emigrate, particularly to France, but also to the USA, Italy or Germany.

Once war broke out, how did the Turkish state, which managed to remain “neutral” until the end of the Second World War, behave towards the Jews who lived within its borders?

Guttstadt: I think we have to differentiate here between anti-Semitism and anti-minority nationalism, which targeted not only the Jews, but other groups too. On the one hand, anti-Semitic tracts like the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion reached Turkey and were translated into Turkish in the 1930s. Following a visit to Germany, Cevat Rıfat Atilhan, who could be described as the father of Islamic anti-Semitism in Turkey, started publishing the anti-Semitic newspaper Millî İnkîlâp (National Revolution) in Istanbul, which contained anti-Semitic caricatures that had been lifted directly out of the Nazi newspaper, Der Stürmer. Although this and other magazines were banned for a certain period, they mark the birth of modern anti-Semitism in Turkey.

Both the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion and Mein Kampf have gone through umpteen new editions to this day. Nationalist measures that affected not only Jews, but also Kurds, Armenians, and Greeks, included forced resettlement, the so-called “wealth tax” – which led to the confiscation of assets of those who were not in a position to pay the arbitrarily fixed and frequently astronomical sums they were required to pay – and forced labour in camps in eastern Anatolia. Although these measures are in no way comparable with the persecution of the Jews at the hands of the Nazis, they destroyed the Jews’ faith in the Republic so utterly that the majority of the country’s remaining Jews left the country in 1947/48.

At this time, Turkish Jews were scattered all over Europe. How did they fare?

Guttstadt: At the start of the war, approximately 25,000 to 30,000 Jews of Turkish origin lived in Europe, most of them in France. Only about 10,000 of them still held Turkish citizenship, which became a matter of life and death during the Holocaust. There were many people who came to Europe as “Ottoman citizens”, but whose place of birth had been assigned to other states once the Empire was no more. In France, it was relatively easy to obtain French citizenship. From the start of the 1930s, the Kemalist Republic began checking the nationality of citizens living abroad and revoking the citizenship of non-Muslims in particular.

| Bild:

Ceremony to mark the opening of the Neve Shalom Synagogue in Istanbul, one of the few remaining synagogues in Turkey: “During World War II, Turkey was not a major country of exile for persecuted Jews,” says Guttstadt | This policy of denaturalisation, which the Turkish state could initially pass off as a normal consequence of the new state order, focussed primarily on the Jews during the Holocaust. In October 1942, Germany delivered an ultimatum to the Turkish government to repatriate its Jewish citizens from the states occupied by the German Reich. Above all, however, the government in Ankara wanted to prevent a mass influx of Turkish Jews and decided to use the instrument of mass denaturalisation as a means of preventing it. What proved particularly fatal in this regard was the fact that according to Turkish law, people who had either voluntarily changed their nationality or had been denaturalised were not allowed to set foot on Turkish soil ever again – even as a tourist or a refugee.

Moreover, in 1938, Turkey passed a secret decree that forbade “foreign Jews who are subject to restrictions in their native countries, regardless of what religion they currently practice” from entering Turkey. With this decree, Turkey adopted the criteria that characterised anti-Jewish legislation in Germany and its allied countries.

What did the Turkish government at the time know about what was happening in the countries controlled by Germany and about the fate of Turkish Jews living in those countries?

Guttstadt: Naturally, the Germans did not tell the Turkish authorities that Jews who were not repatriated would be deported and murdered, but obscured the reality of the situation by saying that they would be “subject to the general measures applied to Jews”. However, in view of the fact that numerous Jewish aid organisations had representatives in Istanbul, Turkey was a one of the places where concrete information about the Holocaust was available. From there, journalists reported about the systematic murder of Jews.

Jews that had escaped the concentration camps or ghettos and managed to make it to Istanbul, were questioned by aid committees and given the assistance they needed. Their reports were passed from Istanbul to other offices around the world. Both journalists and Jewish activists were undoubtedly under observation by the Turkish secret service. In March 1943, the Turkish government newspaper Ayın Tarihi reported about the mass murder of Jews in Germany. Several Turkish Jews living in Europe turned to the Turkish government for help.

About 3,000 Turkish Jews were deported to German concentration camps during the Shoah. To what extent can Turkey be held responsible for their fate?

Guttstadt: The Germans are responsible for depriving these people of their rights and for their persecution and murder. In view of current attempts in Germany to rewrite history again and in view of the German “victim” debate, I refuse to qualify German responsibility in any way. Turkey could have repatriated a much greater number of Jews and opened its borders to refugees. Despite the fact that aid organisations offered to assume the costs that would ensue, the Turkish government generally refused. That being said, Turkey was certainly not the only country to adopt a passive stance.

However, until such time as the Turkish archives are opened, we can only speculate about domestic discussions and criticism of the official policy towards the Jews. We must remember that the Turkish regime at the time was dictatorial; there was a one-party system; the press toed the regime line and was subject to strict censorship. The Jewish community was also completely intimidated and impoverished by the measures taken in the 1940s.

The official Turkish line is that Turkey was a safe harbour for Europe’s Jews.

Guttstadt: Because of its close ties to Germany, Turkey actually had extensive opportunities to save Turkish Jews living abroad. Isolated Turkish diplomats frequently grasped these opportunities. In Paris, for example, Turkish consuls brought about the release of a number of incarcerated Turkish Jews. Turkish consuls in Milan and Vienna also protected individual Jews. Even though these acts were not always performed for purely humanitarian reasons – some consuls may have used their influence to line their pockets – it shows the great latitude they had. In many cases, it was enough to confirm the Turkish citizenship of a Jew to prevent him or her from being deported.

The hiring of German Jewish academics at Turkish universities is often mentioned as a humanitarian act. What is your view?

Guttstadt: It is true that from the autumn of 1933 onwards, a considerable number of German Jewish academics and artists found jobs in Turkey, where they played an outstanding role in building up new universities, hospitals, theatres etc. Even though they were not received for humanitarian reasons, but for reasons of utility, the Turkish government gave these people work, in most cases allowed their families to follow them to Turkey, and protected them against persecution by the Nazi regime. Nevertheless, Turkey was never a major country of exile for persecuted Jews. In terms of numbers, the few refugees that were allowed to enter the country do not appear in any pertinent statistics.

Interview conducted by Sonja Galler

© Qantara.de 2009

Corry Guttstadt: Die Türkei, die Juden und der Holocaust (Turkey, the Jews and the Holocaust) Verlag Assoziation A, Berlin-Hamburg 2008. 520 pages, 26 euros.

Letter to the EditorAdd a comment Qantara.de

Interview with Ishak Alaton

“Turkey Needs a Mentality Revolution”

Ishak Alaton is one of Turkey’s most influential businesspeople of Jewish extraction. Hülya Sancak spoke to him in Istanbul about the current political situation in Turkey and minority rights for Jews, Kurds and Armenians in the country

German Jews in Exile in Turkey

“Haymatloz” in Istanbul and Ankara

When the Nazis took power in 1933, hundreds of thousands of German Jews fled the country. Some of them ended up in Turkey, which was a neutral state and safe haven up until the end of World War II. Ursula Trüper recounts their story and that of the Ruben family

Jewish Life in Istanbul

The Guardians of Hope

Istanbul was once a centre of Jewish life. Now 20,000 Sephardi Jews still live in the city. The writer Mario Levi recreates the spirit of time past in his books, which is also nurtured by a businessman and a linguist. Kai Strittmatter has been exploring Jewish life in Istanbul

Sixty Years of Turkish-Israeli Relations

Partnership in the Shadow of a Threat

Turkey and Israel mark the sixtieth anniversary of their diplomatic relations this year. Theirs has been a fruitful if conflict-ridden relationship. But there has been more than just the desire to make peace between the Israelis and the Arabs. Jan Felix Engelhardt looks back at the start of the relationship Published: 29.05.2009 – Last modified: 30.05.2009