Click here to see the rest of the photos :

Turkish soldiers dressed in Ottoman outfits take part in a ceremony in front of the historical city walls to mark the 558th anniversary of the conquest of Istanbul by Ottoman Turks, in Istanbul May 29, 2011. “The Conqueror”, Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II, captured Istanbul in 1453 which led to the end of the Byzantium Empire.

Turkish soldiers dressed in Ottoman outfits take part in a ceremony in front of the historical city walls to mark the 558th anniversary of the conquest of Istanbul by Ottoman Turks, in Istanbul May 29, 2011. “The Conqueror”, Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II, captured Istanbul in 1453 which led to the end of the Byzantium Empire.

Source: REUTERS / Murad Sezer

The Ottoman era Suleymaniye mosque is covered by fog as the sun sets in Istanbul, November 25, 2009.

The Ottoman era Suleymaniye mosque is covered by fog as the sun sets in Istanbul, November 25, 2009.

Source: REUTERS / Murad Sezer

A Dutch tourist rests before a Turkish bath at the historical Galatasaray hamam in Istanbul September 16, 2009.

A Dutch tourist rests before a Turkish bath at the historical Galatasaray hamam in Istanbul September 16, 2009.

Source: REUTERS / Murad Sezer

An activist offers a rose to a riot policeman during a demostration against the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank in central Istanbul October 6, 2009.

An activist offers a rose to a riot policeman during a demostration against the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank in central Istanbul October 6, 2009.

Source: REUTERS / Osman Orsal

Turkish air force cadets march during a graduation ceremony for 197 cadets at the Air Force war academy in Istanbul August 31, 2009.

Turkish air force cadets march during a graduation ceremony for 197 cadets at the Air Force war academy in Istanbul August 31, 2009.

Source: REUTERS / Murad Sezer

Clouds gather over the Ottoman era Mecidiye mosque and the Bosphorus bridge as Turkish men get ready to jump in to the Bosphorus strait to refresh themselves in Istanbul July 22, 2009

Clouds gather over the Ottoman era Mecidiye mosque and the Bosphorus bridge as Turkish men get ready to jump in to the Bosphorus strait to refresh themselves in Istanbul July 22, 2009.

Source: REUTERS / Murad Sezer

The Bosphorus Bridge is illuminated by the flood of traffic during rush hour, between the two sides of the city across the Bosphorus Straits, in Istanbul, April 7, 2011.

The Bosphorus Bridge is illuminated by the flood of traffic during rush hour, between the two sides of the city across the Bosphorus Straits, in Istanbul, April 7, 2011.

Source: REUTERS / Osman Orsal

A man cooks meat in a window of a restaurant in Istanbul, September 25, 2006.

A man cooks meat in a window of a restaurant in Istanbul, September 25, 2006.

Source: REUTERS / Jerry Lampen

Turkish soldiers dressed in Ottoman outfits take part in a ceremony in front of the historical city walls to mark the 558th anniversary of the conquest of Istanbul by Ottoman Turks, in Istanbul May 29, 2011. “The Conqueror”, Ottoman Sultan Mehme

Turkish soldiers dressed in Ottoman outfits take part in a ceremony in front of the historical city walls to mark the 558th anniversary of the conquest of Istanbul by Ottoman Turks, in Istanbul May 29, 2011. “The Conqueror”, Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II, captured Istanbul in 1453 which led to the end of the Byzantium Empire.

Source: REUTERS / Murad Sezer

May Day protesters shout slogans from a window of a building where they rushed in for protection during clashes between police and Mayday protesters in central Istanbul, May 1, 2008.

May Day protesters shout slogans from a window of a building where they rushed in for protection during clashes between police and Mayday protesters in central Istanbul, May 1, 2008.

Source: REUTERS / Umit Bektas

Bursaspor fans throw seats at rival fans prior to the Turkish Super League soccer match between Besiktas and Bursaspor in Istanbul December 5, 2010.

Bursaspor fans throw seats at rival fans prior to the Turkish Super League soccer match between Besiktas and Bursaspor in Istanbul December 5, 2010.

Source: REUTERS / Murad Sezer

Pro-Palestinian activists wave Palestinian flags during the welcoming ceremony for cruise liner Mavi Marmara at the Sarayburnu port of Istanbul December 26, 2010. Nine Turkish activists died in May when Israeli commandos raided the boat, which was part of

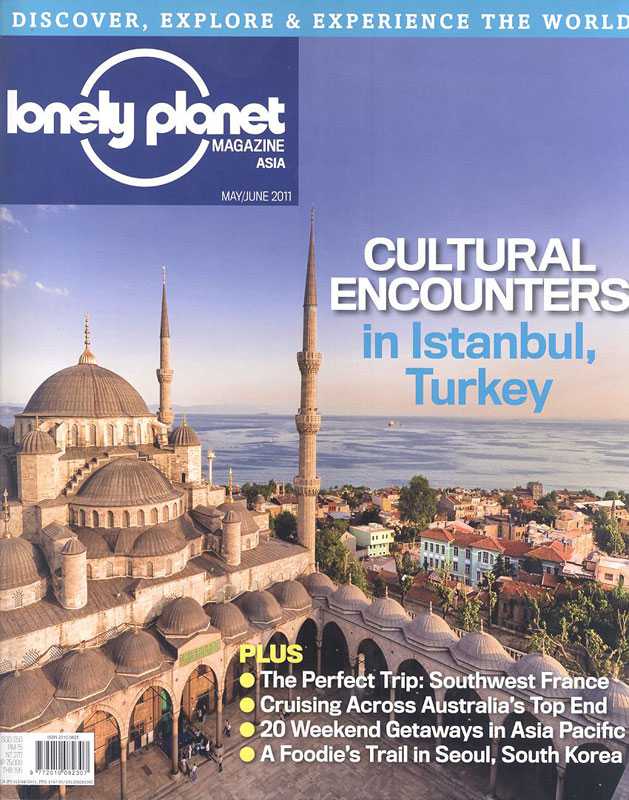

Pro-Palestinian activists wave Palestinian flags during the welcoming ceremony for cruise liner Mavi Marmara at the Sarayburnu port of Istanbul December 26, 2010. Nine Turkish activists died in May when Israeli commandos raided the boat, which was part of a flotilla seeking to break the blockade imposed on the Gaza Strip. The Hagia Sophia is seen in the background.

Source: REUTERS / Osman Orsal

Fenerbahce players celebrate their Turkish Super League championship win as they travel to Sukru Saracoglu stadium for a trophy ceremony in Istanbul May 23, 2011.

Fenerbahce players celebrate their Turkish Super League championship win as they travel to Sukru Saracoglu stadium for a trophy ceremony in Istanbul May 23, 2011.

Source: REUTERS / Osman Orsal

A riot police officer slips and falls while chasing a left-wing demonstrator, near an election campaign point of Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), after clashes broke out during a protest against government

A riot police officer slips and falls while chasing a left-wing demonstrator, near an election campaign point of Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), after clashes broke out during a protest against government in Istanbul June 2, 2011.

Source: REUTERS / Nazim Serhat Firat

Tourists visit the sixth century Byzantinian monument of St. Sophia in the old city in Istanbul, November 16, 2006.

Tourists visit the sixth century Byzantinian monument of St. Sophia in the old city in Istanbul, November 16, 2006.

Source: REUTERS / Fatih Saribas

Muslim women sit on a park bench overlooking the Golden Horn on Marmara Sea in Istanbul, April 3, 2009.

Muslim women sit on a park bench overlooking the Golden Horn on Marmara Sea in Istanbul, April 3, 2009.

Source: REUTERS / Finbarr O’Reilly

Whirling dervishes spin during a Sema ceremony in Istanbul, April 5, 2009.

Whirling dervishes spin during a Sema ceremony in Istanbul, April 5, 2009.

Source: REUTERS / Finbarr O’Reilly

Greek Orthodox pilgrim Ouzinos Panaiotis (L) retrieves a wooden cross, thrown by Greek Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I into the Golden Horn, as part of Epiphany day celebrations in Istanbul January 6, 2010.

Greek Orthodox pilgrim Ouzinos Panaiotis (L) retrieves a wooden cross, thrown by Greek Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I into the Golden Horn, as part of Epiphany day celebrations in Istanbul January 6, 2010.

Source: REUTERS / Murad Sezer

A vintage tram runs along Istiklal street, decorated with New Year lighting, in downtown Istanbul December 29, 2010.

A vintage tram runs along Istiklal street, decorated with New Year lighting, in downtown Istanbul December 29, 2010.

Source: REUTERS / Murad Sezer

A man walks through the snow in a Park in Istanbul January 23, 2010.

A man walks through the snow in a Park in Istanbul January 23, 2010.

Source: REUTERS / Osman Orsal