Written by Steve Royston

I flew into Istanbul a couple of weeks ago to rendezvous with my wife and two other couples. We were en route to a ten-day cruise that started in the city.

The earthquake in Van had taken place only a few days before, and Turkey was in shock. I stopped off in Sultanahmet, the old city that is part of every tourist’s itinerary, and struck up a conversation with the owner of a carpet shop. My new friend – for everybody who wants to sell you a carpet is your friend – was outraged by what he saw as the dilatory response of the government to the disaster.

He pointed to the flags that were flying everywhere to mark Turkey’s national day, and from his personal patriotic standpoint let loose a stream of invective about Prime Minister Recip Tayyip Erdogan and his government. What particularly irked him was that ten years ago Erdogan had put in place an emergency tax in order to raise a fund for mitigating precisely the kind of disaster that struck Van.

Istanbul is not immune to earthquakes, and some estimate that up to 600,000 buildings in the city are vulnerable to collapse because they do not meet national earthquake protection standards. The earthquake tax has apparently raised over $50 billion, but instead of keeping the money in reserve to deal with disasters like the Van earthquake, the government has diverted most of the funds into infrastructure projects– primarily highway development.

The result has been that Turkey has had to ask for international assistance to deal with the situation in Van, something that my new friend believes should never have been necessary if the revenues from the special tax had been properly applied. Clearly, he is not the only person in Turkey with that view. When we passed through Istanbul on the way home from the cruise, I happened upon an article by Yousef Kanli in the Hurriyet Daily News, Istanbul’s English-language newspaper. In ‘I don’t have socks, Mr President!’, Kanli writes:

“Well, back in 1999 this country initiated a revolutionary – and biting – quake tax on a variety of consumer products including cigarettes, alcohol, fuel and so on. Since then, 50 billion dollars have been collected, giving the state a lot of resources to deploy against natural disasters. Instead, this government used that money to building the double-lane highways it pledged in its election campaign. Should the state not be more serious in its dealings with its citizens?”

Van is not one of Turkey’s better-known cities. But almost a century ago it was the scene of one of the few instances of armed resistance by the beleaguered Armenian minority against the Ottoman army during World War I. 1915 was the year of what the Armenians regard as genocide against their minority community in the Ottoman Empire. Estimates of the number of people killed by the Ottoman authorities across the Empire range between 500,000 and 1.2 million. The alleged genocide is still a hot political issue between Turkey – whose government disputes the definition of the events of 1915 as genocide – and the neighbouring modern state of Armenia – which demands Turkish acceptance of responsibility for the massacres as a precondition for normalisation of relations between the two countries.

Memories and interpretation of these events serve as the backdrop for Turkish writer Elif Shafak’s outstanding 2006 novel “The Bastard of Istanbul”, which was on my reading list for the cruise. The last time I visited Istanbul I came armed with two of Nobel prizewinning author Orhan Pamuk’s books on the city – “My Name is Red”, and “Istanbul: Memories and the City”. Anyone interested in getting under the skin of modern Turkey should as a minimum look at the works of Shafak and Pamuk.

What the two authors have in common is that both faced prosecution under Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code, which states that “A person who, being a Turk, explicitly insults the Republic or Turkish Grand National Assembly, shall be punishable by imprisonment of between six months to three years.” Shafak was indicted for the words she put in the mouths of her characters in her novel. Pamuk for a public statement referring to the death of 1 million Armenians. The specific indictments referred to accusations that the authors had “insulted Turkishness”. In the end, both prosecutions were dropped.

Critics of Turkey’s touchy relationship with its past, as enshrined in Article 301, have used such cases to argue against the country’s prospective membership of the European Union. Much as I sympathise with the stance of both authors on freedom of expression, those critics should remember that challenges to historical orthodoxy can be also perilous within the EU, as the historian and alleged holocaust denier David Irving discovered when found guilty under Austrian law prohibiting “National Socialist Activities” and sentenced to three years in jail.

Istanbul has always been a hotbed of debate, whether prohibited or not. From its birth as Constantinople it was wracked with arguments, sometimes violent, about issues such as the true nature of Jesus Christ. Did he have a dual nature as a man and as the Son of God? Does the Holy Spirit emanate from the father and from the son? Theological debate continued after the conquest of the city by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II. Throughout the Ottoman rule the city was host to Orthodox Christians, Sunni Muslims, Sufi sects and Jews. The Ottoman court was rife with plots, intrigues, purges and the ruthless actions of successive Sultans to consolidate its power.

Today, even a casual tourist will find it hard not to bump into the current political issues – the Kurdish insurgency, the strains between the followers of Kemal Ataturk’s secular political philosophy and the growing Islamist hue of the Erdogan government. Much as Turkey is touted within the Middle East as the role model for the moderate Islamist factions that are gaining influence in the wake of the Arab Spring – such as the Tunisian Ennahda party – within the country there seems still to be anxiety about the future. My friend the carpet seller is by no means optimistic. He believes that the next two years will determine whether the differences of opinion will degenerate into social discord. When two of our friends took a guided tour of the Ayia Sofia museum, their guide took them into a corner, and speaking quietly so as not to be overheard, told them of his concerns – intolerance, arrests and the slow erosion of the secular society established by Atatürk.

Yet the media in Turkey still seems a long way from the muzzled press in some of its neighbours in the Middle East. For example, the Daily News carried an opinion piece by Mustafa Aykol decrying what he called Turkey’s secular blasphemy laws prohibiting criticism of Atatürk:

“The real issue, though, is not who Atatürk really was. The real issue is that we still don’t have the right to discuss that freely in Turkey. Prosecutors are always ready to put critics on trial for “insulting Atatürk.” And millions of hate-filled Kemalists are always ready to unleash the ugliest insults against those who simply think that Atatürk was a mortal who made serious mistakes.

The zeal here is most staggering, and it is only paralleled by the “blasphemy laws” that are found in some Islamic states such as Pakistan. In those countries, what is protected by law from any “insult” (and actually criticism) is Islam and its sacred symbols such as the Prophet Muhammad. In Turkey, a similar veneration is imposed by law, but this time for “Turkishness” and Atatürk.

Which gives us hints about the bizarre nature of Turkey’s much-cherished “secularism.” Unfortunately, this principle is not about creating a civil public square in which various religions and philosophies can co-exist and engage in rational discussion. Turkish secularism is rather about replacing traditional religion, especially Islam, with ersatz religion. Atatürk is the latter’s both demigod and prophet, and his words and deeds constitute a new form of scripture.

To me, that would have been still fine, had Kemalism existed as mere ideology and belief, to be followed by those who are convinced and inspired. The problem is that it is the official creed that is imposed on everyone, and that its blasphemy laws threaten us all.”

Earlier in his piece, Aykol discusses the furore that arose when a journalist referred to Atatürk as a dictator. I very much doubt that when the generals ruled Turkey he would have been able even to suggest anyone might hold that opinion. So I guess that’s progress of a sort.

Byzantine citizens of Constantinople who argued about the definition of the Holy Trinity would, if they were alive today, smile knowingly as their successors debate the definition of genocide and dictatorship.

All that physically remains of the old Constantinople are the land walls, the magnificent Ayia Sofia, a couple of other churches and a host of ground level archaeological sites. Yet spiritually, today’s Istanbulus are not so different from their Byzantine predecessors. The majority may be now be Muslim, but the delight in debate and intrigue has survived throughout the city’s long history.

That’s a major reason why Istanbul is one of my favourite cities in the world.

And for me, a newly discovered delight: the view across the city from the Hamdi restaurant near Galata Bridge. On top of the view, Hamdi is held by many to be makers of the finest kebabs in Turkey. Magnificent panorama, memorable kebabs. A perfect way to round off the trip.

Short URL: https://mideastposts.com/middle-east-society/middle-east-travel/istanbul-postcard-still-arguing-after-18-centuries/

Green attractions: Beautiful retreats like Abant Lake lie just a couple of hours from bustling Istanbul

Green attractions: Beautiful retreats like Abant Lake lie just a couple of hours from bustling Istanbul

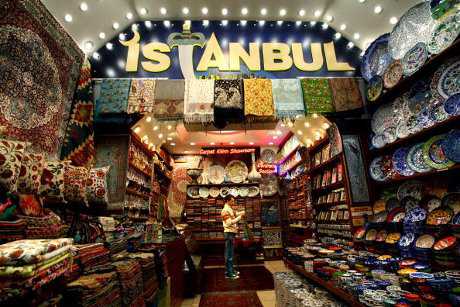

Exotic: The spice market made a fascinating stop-off while in the big city

Exotic: The spice market made a fascinating stop-off while in the big city

Mudurnu magic: The traditional buildings in this town have a more alpine feel than Turkish

Mudurnu magic: The traditional buildings in this town have a more alpine feel than Turkish