By Laura Snapes

Posted on 11/23/10 at 05:45:01 pm

PJ Harvey releases her ninth studioalbum ‘Let England Shake’ on February 14. Laura Snapes has heard it…

Let England Shake

You might know this one from Polly?s performance on The Andrew Marr Show earlier this year, which you can watch below. Now though, the Four Lads ?Istanbul (Not Constantinople)? sample has been scrapped (?It actually became something that was drawing the song back rather than letting it become its own living entity, so we got rid of that in the end,? Polly explained), and what sounds like a hollow music box salvaged from a decrepit carousel mimics that song?s melody instead.

It?s still played on autoharp, the chord progressions of which are so subtle that it almost becomes drone-like, Mick Harvey gracefully splashes the cymbals on every autoharp downstroke, and a wind section adds long, off-key chords for gravitas. Most striking of all though is PJ?s voice ? high, brutally direct and confessional in places on ?White Chalk?, here it?s layered and spritely, flirting with her regional accent on certain lines. It sounds like she?s having fun with it?

The Last Living Rose

There?s a pretty good quality video of PJ playing this at last year?s Camp Bestival. The recorded version is much the same in terms of voice and guitar, but with added spindly percussion and plaintive, sparingly used horns. There?s real emphasis at the end of this line – ?past the Thames river glistening, like gold, hastily sold, for nothing, NOTH-II-IING!? ? which seems much more of a direct political statement than we?re used to from Polly.

The Glorious Land

?This album?s not solely about war, it?s about very many different things ? it?s the world we live in, and part of that is war,? PJ said in our interview. This song more than any other present seems directly related to the act of battle itself. There?s a shaky but liturgical rhythm to the drums which open the minute-long introduction, uneasy single bass notes, and then a bugle, which rears its ?Reveille? throughout the song, the lyrics of which make up a series of call and responses.

All the lines are repeated twice, then answered twice: ?How is our glorious country ploughed, not by iron ploughs,? is met with ?our lands are ploughed by tanks and feet, fee-eet maa-arrching?. With more lines, her voice grows ever higher, the chorus sees her playing with intonation again ? ?oh, America? is sometimes ?oh, A-me-ri-CAH?, followed by a rattling childlike chorus of ?oh Eng-err-laa-aand?. The only line that remains unanswered is, ?how is our glorious land bestowed?? her voice borderline hysterical, but still restrained.

The Words That Maketh Murder

?I?ve seen and done things I want to forget,? Polly sings, whilst a detuned autoharp echoes limitlessly. ?I?ve seen soldiers fall like lumps of me-ee-eat.? Right, so here she?s definitely in character mode as she explained in the magazine, her voice a shellshocked but theatrically coy rattle.

The lyrics are a harrowing portrait of war ? nothing you couldn?t garner from the television or newspaper, but images of dismembered limbs and ?a corporal whose nerves were shot? hang oppressively before she and collaborator John Parish question, ?What if I take my problem to the United Nations?? come the end. All you critics who quarrelled with her move into narrative lyrics come the release of ?To Bring You My Love? ? gird your loins.

All And Everyone

At first, this feels a lot lighter, with open, ringing autotune chords. There?s a certain air of resignation, as amplified by an organ, meek as though played by an old lady in the parish vestry. After about forty seconds though, it all tails off and weighted, dissonant autoharp clanks underneath, making chords out of different detunings.

Again, we?re on the battlefield ? and ?death was everywhere, and everyone? – but mentions of beaches and sea along with the richly drab horns give it more of an old-timey D-Day feel than any modern war. The clanking, detuned strings chime with gunfire regularity, cymbals occasionally adding canon-like emphasis, but vanishing during the chorus, which drones at a half pace to Polly?s frantic descriptions during the verse.

On Battleship Hill

Initially the warmest sounding track so far, kicking off with an almost major chord echoing, comforting electric jangle. There?s no edge or sharpness to the guitar part at all, until a stuttering classical guitar falters on a single played string whilst Polly trills, ?The scent of time has carried on the wind? in a nigh-on hysterial alto. Here she?s lamenting the senescent damage that time brings upon humans, but not on the land, which ?returns to how it?s always been, time carried on the wind.? A jarring, eerie listen.

England

A love letter to England; here, it?s this character ? or Polly?s ? raison d?être, and in the country?s dying throes, her protagonist wilts accordingly. It?s an unhinged listen, starting off with just her voice half singing, half wailing, ?laah-dah-da-dah? like a slightly mad child, whilst a thinner, far more distant, approximation of her voice is trapped underneath, almost mangled into Middle Eastern intonation that recalls routine prayer calls. Again, she?s dealing with the torture of aging ? ?I have searched for your springs,? she sings, ?but people, they stagnate with time, like water, like air??

In The Dark Places

Back to that raw, more live feel; the guitar a thick burr beneath as she and John again roam the landscape, witnessing ?our young men / hit with guns / in the dirt / and in the dark places?. It?s probably the most affecting song on the record, the verse all searching high notes, then dropping into an almost spoken chorus, where Polly and John take turns leading verses of ?And not one man has / and not one woman has / revealed the secrets of this world.?

Bitter Branches

Drums dash at a gravelly chase, the pace much faster than anything else thus far, and the ominous guitar sprinting behind recalls the oppressive chase of ?Uh Huh Her?. As on the opening song, Polly?s having fun with her voice again ? it veers mercurially between an unnerving coo during the drops and an echoing shriek on the verses as she castigates the trees: ?Bitter branches / Spreading out / There?s none more bitter-er-er / than the wood.?

Hanging In The Wire

And the oppressive sound lifts? We?re still out in the countryside, but rather than dendrophobic railings, here the lyrics trace a lone rambler who ?sees the mist rise over no man?s land.? Beneath her dislocated, high voice, the song?s piano-led, but wouldn?t have fit on ?White Chalk? due to its sweet, high classical refrain ? though she does mention ?the white cliffs of Dover.?

Written On The Forehead

So the sample was stripped from ?Let England Shake?, but there?s one here ? an old reggae track called ?Blood And Fire?. I?m not sure who did it originally ? the only thing YouTube?s throwing up is a really shit UB40 cover of it? Anyway, as a muffled voice chants, ?Blood, blood, blood, blood and fire? in the background, Polly?s voice trembles, ?People throwing Dinars / At the bellydancers.?

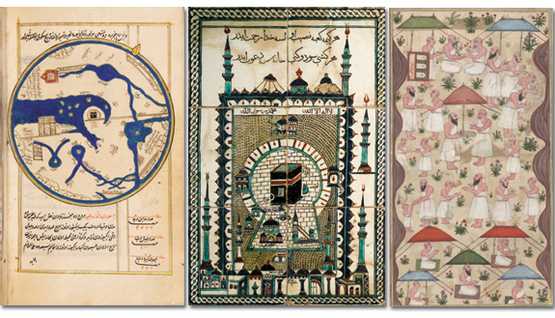

We?re not on homely pastoral turf any more, with the mention of Dinars seeming to link back to the trapped voice in ?England? that sounds like prayer call. Given that the original sample on ?Let England Shake?, ?Istanbul (Not Constantinople)? referred to the Turkish people reclaiming/renaming their capital city as its original name was of Latin origin, so there seems to be a parallel Middle Eastern narrative or set of references running through the record.

The Colour Of The Earth

John Parish kicks off this song, singing, ?Louis was my dearest friend / Fighting in the ANZAC trench.? Quick history lesson for you here: this refers to a fight to capture the Ottoman capital of Istanbul ? then known as Constantinople ? during the first world war, a battle that resulted in heavy casualties on both sides.

Which lends credence to the theory I was mooting on ?Written On The Forehead? about the dual narrative. When Polly talked of the album being about war in parts, my instant assumption would be that it?s a reaction to the military activity of recent years, but if it is, she?s chosen a more recondite fight with which to contrast it, or in which to set her observations.

The instrumentation here is autoharp again, blurred by infinite reverb (perhaps due to the high ceilings of the church in which they recorded), with subtle chord changes that are as plain in tone as an unexotic landscape, but as breathtaking as a bird?s eye view of same.

For the full, exclusive interview with PJ Harvey get the new issue of NME magazine. It’s on newsstands across the UK from tomorrow (November 24), or available digitally worldwide now.