The arts and the economy might be prospering, but critics fear old Istanbul is turning into a new Dubai

by Sheila JohnstonSunday, 21 April 2013

Late on a spring Friday evening, İstiklal Caddesi, the main shopping thoroughfare in Istanbul’s Beyoğlu district, exudes all the delicious traditional Turkish aromas: roasting chestnuts, fierce black coffee, döner grills and simit, İstanbul’s bagel, still selling like hot cakes way after midnight. Most of all, though, milling with the crowd, you are struck by something else, something less familiar these days, in Europe anyway: the smell of money.

While the old economies are on their knees, Turkey has been booming: 9.2 percent growth in GDP in 2010, 8.5 percent in 2012. Last year the motor spluttered and stalled – only 2.2 percent growth – but is still chugging along nicely enough.

Since I last visited the city seven years ago, the skyline has been transfigured (many say, disfigured) with shiny new high-rise buildings. İstiklal Caddesi is lined with cash dispensers every few metres, with more lines of people eager to use them. (Pictured right: a lottery ticket seller stands guard by the Swatch shop on İstiklal Caddesi)

Since I last visited the city seven years ago, the skyline has been transfigured (many say, disfigured) with shiny new high-rise buildings. İstiklal Caddesi is lined with cash dispensers every few metres, with more lines of people eager to use them. (Pictured right: a lottery ticket seller stands guard by the Swatch shop on İstiklal Caddesi)

In 2010 Istanbul was a European City of Culture. It was a strategic move designed partly to boost Turkey’s application to join the European Union. Decades after making that bid, the country’s still waiting. Though, frankly, joining the Eurozone is looking less attractive by the minute.

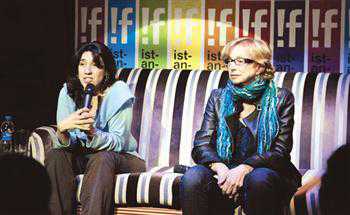

“The economy is thriving here and the arts are too. Private museums and galleries are opening one after the other,” observes Azize Tan, (pictured below left), the Director of the Istanbul Film Festival which, now in its 32nd year, has bravely kept afloat through foul weather and fair: the current edition, just finished, attracted guests including Peter Weir, Patricia Arquette, Carlos Reygadas and Bille August.

Run under the aegis of the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts, which also stages theatre, music and art events throughout the year, its principal sponsor today is Akbank, whose spacious four-floor gallery at the top end of İstiklal Caddesi is the festival’s HQ (sponsors are the main source of the festival’s funding; it receives nothing from the city).

Run under the aegis of the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts, which also stages theatre, music and art events throughout the year, its principal sponsor today is Akbank, whose spacious four-floor gallery at the top end of İstiklal Caddesi is the festival’s HQ (sponsors are the main source of the festival’s funding; it receives nothing from the city).

So it’s the banks and rich private patrons that are investing in the arts, specifically art: Istanbul boasts around 150 galleries, two biennials — one for design and one for art — and several contemporary art fairs. The following day I wander down İstiklal Caddesi to see SALT, an opulent, cavernous building owned by Garanti Bank with a walk-in cinema, bookshop, tearoom and three floors of exhibition space, currently dedicated to a show about the notorious 1977 Labour Day massacre in Istanbul, at which 33 people died.

A second SALT venue in Istanbul is twice as large again and there is a third outlet in Ankara. “We have a vibrant art scene,” says Elif Obdan, who works with Tan at the Foundation. “But to make it sustainable there are things to do. Everyone wants to visit Istanbul.” She pauses. “It’s different when you live here, though.”

For critics are talking darkly of bubbles, of boom and bust, of unchecked speculation that will swallow up old Istanbul and turn it into a new Las Vegas, Disneyland, Dubai. Today the perception is that while 2010 did prompt some much needed restoration programmes, but that ephemeral year in the spotlight was, overall, a disappointment.

“We are growing too fast and sometimes hasty decisions are being made. There’s no state control and no transparency,” Tan says. “I’m not against change. But we do need to talk about what’s going on. It’s not always the point to have something new. In 10 years’ time nothing will survive.”

Also on İstiklal Caddesi, security personnel guard the entrance to the vast, Demirören shopping mall. Two listed historical buildings were razed in 2010 to make way for the bling, pseudo-classical edifice which towers over its surroundings and whichMilliyet newspaper described as “a hormone-filled pumpkin”. The manoeuvring, deceptions and extended scandal around the project, are all chronicled in detail here.

Also on İstiklal Caddesi, security personnel guard the entrance to the vast, Demirören shopping mall. Two listed historical buildings were razed in 2010 to make way for the bling, pseudo-classical edifice which towers over its surroundings and whichMilliyet newspaper described as “a hormone-filled pumpkin”. The manoeuvring, deceptions and extended scandal around the project, are all chronicled in detail here.

Turn right after you pass Demirören and you enter a dark, dingy back alley strewn with dust and builder’s rubble. This is Yeşilçam Sokağı, once known as the Turkish Hollywood. Production houses were based here, and cinemas; Kemal Atatürk went to the movies there. It was formerly the heart of the Film Festival. Now it’s at the centre of Istanbul’s latest arts controversy.