|

|

Tag: HUMAN RIGHTS

-

Tougher rules to stop abuse of student visa system

Tougher rules have been brought in to stop people abusing the student visa system to remain illegally in the UK.

The government has faced criticism that the system is too lax Home Secretary Alan Johnson said 30% of migrants who came into the UK were on student visas and a number were adults taking short courses, not degrees.

Under the new rules, applicants will need to speak English to near-GCSE level and those on short courses will not be able to bring dependants.

The Tories said the system had been the “biggest hole in border controls”.

The Home Office would not confirm reports the changes may cut visas issued this year by tens of thousands.

A spokesman said a review of student visas had been ordered in November. In 2008/9, about 240,000 student visas were issued by the UK.

News of the new measures comes a week after student visa applications from Nepal, northern India and Bangladesh were suspended amid a big rise in cases.

‘Legitimate study’

Last year the UK introduced a system requiring students wishing to enter the country to secure 40 points under its criteria.

However, the government has faced criticism that this has allowed suspected terrorists and other would-be immigrants into the UK, only for them to stay on despite their visas being temporary.

Speaking on the BBC’s Andrew Marr Show, the home secretary denied the system had been lax before.

“By 2011, we will have the most sophisticated system in the world to check people not just coming into the country but to check they have left as well,” he said.

He said the UK remains open to those foreign students who want to come to the UK for legitimate study.

“We are the second most popular location for people going into higher education,” he said.

“We have to be careful that we are not damaging a major part of the UK economy, between £5bn and £8bn.”

Immigration Minister Phil Woolas told the BBC’s Politics Show 200 bogus colleges had been closed.

“Students have foreign national identity cards. We have the e-Border counting in and counting out,” he said.

“The latest proposals are a response to the moves by people who are trying to get round the system.”

Under the measures, effective immediately:

• Successful applicants from outside the EU will have to speak English to a level only just below GCSE standard, rather than beginner level as at present

• Students taking courses below degree level will be allowed to work for only 10 hours a week, instead of 20 as at present

• Those on courses which last under six months will not be allowed to bring dependants into the country, while the dependants of students on courses below degree level will not be allowed to work

• Additionally, visas for courses below degree level with a work placement will also be granted only if the institutions they attend are on a new register, the Highly Trusted Sponsors List.

Liberal Democrat home affairs spokesman Chris Huhne said the UK needed to “restore immediately control of our borders”.

“The biggest hole in the student visa system is caused by the Tory and Labour abolition of exit checks, which means we do not know if someone has left once their visa runs out,” he said.

Conservative shadow home secretary Chris Grayling said the student visa system had been the “biggest hole in our border controls for a decade”.

“Ministers should be ending the situation where a student visa is a way of coming to the UK to stay, by banning the practice of moving from course to course in order to stay on and stopping overseas students from applying for work permits without going home first,” he said.

The party has also proposed that overseas students should pay a cash deposit which would be lost if they did not leave the country when their course finished.

And Conservative backbencher Mark Pritchard has gone further and proposed universities withhold degree certificates until foreign students can prove they have returned to their home countries.

But Mr Johnson said Mr Grayling’s plan would just add another level of bureaucracy.

“Many of these students, if they are coming here using this route for illegal migration, will pay thousands of pounds to usually criminal gangs,” he said.

“The thought of losing a bond is not going to solve this problem.”

Source: news.bbc.co.uk, 7 February 2010

-

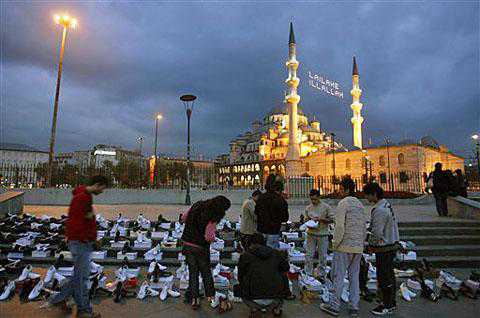

The Rise and Rise of Turkey

By PATRICK SEALEPublished: November 4, 2009It is generally accepted that America’s destruction of Iraq overturned the balance of power in the Gulf, opening the way for the Islamic Republic of Iran to emerge as a major regional power, able to challenge the dominance of Sunni Arab states and pose as a rival to both Israel and the United States.

Its influence has spread to Iraq itself — now under Shiite leadership — and beyond to Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and even perhaps to Zaidi rebels in northern Yemen fighting the central government in Sana‘a, a development that has aroused understandable anxiety in Saudi Arabia.

However, the Iraq war has had another important consequence that is also attracting serious notice. America’s failure in Iraq — and its equal failure to tame Israel’s excesses — has encouraged Turkey to emerge from its pro-American straitjacket and assert itself as a powerful independent actor at the heart of a vast region that extends from the Middle East to the Balkans, the Caucasus and Central Asia.

The Turks like to say that whereas Iran and Israel are revisionist powers, arousing anxiety and even fear by their expansionism and their challenge to existing power structures, Turkey is a stabilizing power, intent on spreading peace and security far and wide.

Turkey is extending its influence by diplomacy rather than force. It is also forging economic ties with its neighbors, and has offered to mediate in several persistent regional conflicts. It has, however, not hesitated to use force to quell the guerrillas of the PKK, a rebel movement fighting for Kurdish independence.

But even here, Turkey is now using a softer approach. The rebels have been offered an amnesty and Turkey’s influential foreign minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, has this past week paid a visit — the first of its kind — to the Kurdish Regional Government in northern Iraq. There is even talk of Turkey opening a consulate in Erbil.

In recent years, Turkey’s diplomacy has scored many successes, winning great popularity in the Arab world and strengthening Turkey’s hand in its bid to join the European Union. Some people would go so far as to argue that there is no future for Turkey without the E.U., and no future for the E.U. without Turkey.

Turkey’s dynamic multi-directional foreign policy started to take shape when the Justice and Development party, or AKP, came to power in 2002 under Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Abdullah Gul, now president of the Turkish Republic. These men are rightly considered to be conservative and moderately Islamic — their wives wear headscarves — but they are careful to stress that they have no ambition to create an Islamic state. Turkey’s population may be largely Muslim, but the state itself is secular, democratic, capitalist and close to both the West and the Arab and Muslim world. Indeed, Turkey sees itself as a bridge, vital to both.

Ahmet Davutoglu is credited with providing the theoretical framework for Turkey’s new foreign policy. He was Mr. Erdogan’s principal adviser before being promoted foreign minister.

Two visits in October illustrate Turkey’s activisim. Prime Minister Erdogan, accompanied by nine ministers and an Airbus full of businessmen, visited Baghdad, where he held a session with the Iraq government and signed no fewer than 48 memoranda in the fields of commerce, energy, water, security, the environment and so forth.

At much the same time, Foreign Minister Davutoglu was in Aleppo, where he signed agreements with Syria’s foreign minister, Walid al-Muallim, of which perhaps the most important was the removal of visas, allowing for a free flow of people across their common border.

Turkey also broke new ground in October by signing two protocols with Armenia, providing for the restoration of diplomatic relations and the opening of the border between them. Not surprisingly, Turkey’s ally Azerbaijan has strongly objected to this development, since it is locked in conflict with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh, an Armenian-populated pocket of Azerbaijan occupied by Armenian forces.

Indeed, Turkey’s protocols with Armenia are unlikely to be fully implemented until Armenia withdraws from at least some of the districts surrounding Karabakh — but, at the very least, a historic start has been made toward Turkish-Armenian reconciliation.

From the Arab point of view, the most dramatic development has undoubtedly been the cooling of Turkey’s relations with Israel. The relationship has been damaged by the outrage felt by many Turks at Israel’s cruel oppression of the Palestinians, which reached its peak with the Gaza War.

Even before the assault on Gaza, Prime Minister Erdogan — a strong supporter of the Palestine cause — did not hesitate to describe some of Israel’s brutal actions as “state terrorism.” A total breach between the two countries is unlikely, but relations are unlikely to recover their earlier warmth so long as Israel’s hard-line prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and his foreign minister, Avigdor Lieberman, remain in power.

Underpinning Turkey’s diplomacy is its central role as an energy hub linking oil and gas producers in Russia and Central Asia with energy-hungry markets in Europe.

One way and another, a resurgent Turkey is rewriting the rules of the power game in the Middle East in a positive and non-confrontational manner. This is one of the few bright spots in a turbulent and highly inflammable Middle East.

-

TV Show Deepens Split Between Israel and Turkey

By NICHOLAS BIRCH, CHARLES LEVINSON and MARC CHAMPION

A war of words ignited by a new Turkish TV series depicting Israeli military atrocities escalated Friday, shaking what is probably Israel’s strongest partnership in the Middle East.

The first episode of the series, “Separation,” aired Wednesday on the public channel TRT, showed what appeared to be an Israeli soldier gunning down an unarmed Palestinian girl in a cul de sac. Shortly afterward, another soldier shoots a newborn baby.

The images sparked outrage in Israel. Labor unions said they would boycott Turkey as a vacation destination, and Israel summoned Turkey’s ambassador Thursday to lodge a protest. Israeli Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman said in a statement Thursday the series “would not be appropriate in an enemy country and certainly not in a state which maintains diplomatic relations with Israel.”

Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu responded Friday by criticizing Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. He said a recent decision to exclude Israel from planned North Atlantic Treaty Organization exercises in central Turkey was made in response to public outrage in Turkey over Israel’s treatment of Palestinian civilians in the Gaza Strip.

“While the tragedy in Gaza continues, nobody should expect us to put on military displays of this sort,” Mr. Davutoglu said.

As for the TV series, Mr. Davutoglu said: “Turkey is not a country based on censorship.”

Officials and analysts in both countries said the split reveals Ankara no longer needs or wants Israel the way it once did.

The two countries have long had strong diplomatic and trade relations, and Turkey has been a substantial buyer of Israeli military hardware. For years, Israeli pilots trained in Turkish airspace. As recently as August, Turkey took part in joint naval exercises with Israel.

But the ties were built in a period when Turkey felt hemmed in on all sides, analysts say. In the 1980s and 1990s, Turkey had poor relations with Iraq and shared with Israel a deep suspicion of Iran. It was also fighting a guerrilla war with Kurdish militants. In 1998, it came close to war with Syria. Turkey was also in conflict with Greece over Cyprus, while then communist Bulgaria and Armenia were historical and Cold War rivals. Ankara needed Israel’s military hardware and intelligence sharing.

“In the 1990s, Turkish foreign policy was guided by security issues, and that pushed Turkey closer to Israel,” says Kadri Gursel, a columnist for the centrist daily Milliyet.

But under Mr. Davutoglu and his boss, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey has worked hard to fix those problems and reintegrate into the region. This month, Turkey signed significant agreements with Armenia, Syria and Iraq.

“There is no need for this [partnership with Israel] anymore,” said Huseyin Bagci, professor of International Relations at the Middle East Technical University in Ankara.

Mr. Bagci predicts that Turkey increasingly will look to Italy, France and other suppliers to buy arms, rather than Israel.

The breakdown in relations also appears personal. Mr. Erdogan walked off the stage at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January after clashing with President Shimon Peres of Israel over the conflict in Gaza. In a recent interview with The Wall Street Journal, Mr. Erdogan was still simmering.

“If you look at Gaza, 1,500 people died, 5,000 people were wounded, infrastructure, the superstructures were all demolished. … What happened afterwards? There was nothing,” said Mr. Erdogan.

Israel and some Turkish analysts see an ideological component to the dispute, noting the Islamist roots of the ruling Justice and Development Party. “We’ve seen Turkey evolve and change since Erdogan’s Islamic party took power,” the senior Israeli official said.

Mr. Erdogan, in the interview, insisted his position wasn’t driven by identification with Muslim Palestinians, but by the need for honesty and fairness.

Turkish officials insist the relationship is far from dead. “Let’s make no mistake. We value a continuation of relations with Israel, but not at any cost,” said ruling-party official Suat Kiniklioglu.

Write to Charles Levinson at [email protected] and Marc Champion at [email protected]

Printed in The Wall Street Journal, page A9

-

A new role for Turkey

Friday, October 16, 2009

Article |

The Boston Globe | A new role for Turkey By Stephen Kinzer

October 15, 2009REACHING LAST weekend’s diplomatic breakthrough between Turkey and Armenia was not easy. It took six weeks of secret talks in Switzerland, seven last-minute phone calls from Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton to the two countries’ foreign ministers, and a wild ride in a Zurich police car, lights flashing and siren shrieking, for a Turkish diplomat carrying a revised draft of the accord.

This breakthrough could also be said to have taken 16 years, the length of time the Turkey-Armenia border has been shut, or 94 years, the time that has passed since Ottoman Turkish forces slaughtered hundreds of thousands of Armenians in what is now eastern Turkey.

In the end, pragmatism prevailed over emotion. Armenia is a poor, landlocked country that desperately needs an outlet to the world. Turkey is a booming regional power, but suffers from its refusal to acknowledge the massacres of 1915. With this accord, each side helps solve the other’s problem. The border is to be reopened and diplomatic relations restored, giving Armenia a chance to rejoin the world. Questions about what happened in 1915 – was it genocide? – will be submitted to historians for “impartial scientific examination.’’

The most bizarre aspect of this process was the effort by Armenians in France and the United States to derail it. Earlier this month in Paris, President Serge Sarkisian of Armenia was met by shouts of “Traitor!’’ and had to be protected by riot police. The potent Armenian-American lobby also rallied against the accord.

If President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran proposed that impartial historians examine the question of whether the Holocaust actually happened, most Jews would presumably accept happily. The failed rebellion by Armenians in the diaspora suggests that some are trapped by the past; their cousins back home, meanwhile, seek a better future.

“There is no alternative to the establishment of relations with Turkey without any precondition,’’ Sarkisian said as the new accord was signed. “It is the dictate of the time.’’

Both parliaments must ratify the accord. There will be disagreements over the Nagorno-Karabakh enclave, which Armenia occupies but which the rest of the world considers part of Azerbaijan, Turkey’s ally. Nonetheless, both countries seem resolved to thaw this long-frozen conflict. They will probably do whatever necessary to overcome remaining obstacles.

The accord will allow trade between the two countries to resume. It will also make it easier for Armenians to visit magnificent monuments from their past that lie within modern-day Turkey. Beyond that, it has far-reaching geopolitical importance.

For nearly all of its 86 years as a state, Turkey has kept a low profile in the world. Those days are over. Now Turkey is reaching for a highly ambitious regional role as a conciliator and peacemaker.

When Turkish officials land in bitterly divided countries like Lebanon or Afghanistan or Pakistan, every faction is eager to talk to them. No country’s diplomats are as welcome in both Tehran and Jerusalem, Moscow and Tblisi, Damascus and Cairo. As a Muslim country intimately familiar with the region around it, Turkey can go places, engage partners, and make deals that the United States cannot.

This new Turkish role holds tantalizing potential. Before Turkey can play it fully, though, it must put its own house in order. That is one reason its leaders were so eager to resolve their country’s dispute with Armenia.

Turkey has one remaining international problem to resolve: Cyprus. Then it must solidify its democracy at home. That means lifting restrictions on free speech and fully respecting minority rights not just those of Kurds, whose culture has been brutalized by decades of repression, but also those of Christians, non-mainstream Muslims, and unbelievers.

Under other circumstances, Egypt, Pakistan, or Iran might have emerged to lead the Islamic world. Their societies, however, are weak, fragmented, and decomposing. Indonesia is a more promising candidate, but it has no historic tradition of leadership and is far from the center of Muslim crises. That leaves Turkey. It is trying to seize this role. Making peace with Armenia was an important step. More are likely to come soon.

Stephen Kinzer is the author of “Overthrow: America’s Century of Regime Change From Hawaii to Iraq.’’

© Copyright 2009 Globe Newspaper Company.