Kings and Generals’ historical animated documentary series on the history of Ancient Civilizations and Nomadic Cultures continues with a video on the Seljuk Turkification of Anatolia – the period that started in the XI century with the battle of Manzikert and was largely concluded by the XV century when the Ottomans rose to power, as the Seljuks and other Turkic peoples entered Anatolia, slowly pushing the Greeks and other locals to the coastal regions, slowly weakening the Eastern Roman Empire.

Tag: History

-

Turkey: The land a dictator turned into a democracy

Monday, Oct. 12, 1953

He who loves the rose should put tip with its thorns.

—Old Turkish saying

ONE day in 1853, Nicholas I, Czar of all the Russias, peered southward over his aristocratic nose and voiced the opinion that Turkey was indeed “the sick man of Europe.” Exactly 100 years later, an astute and wealthy Texan named George McGhee, at the time U.S. Ambassador to Turkey, looked out over the green plains of Anatolia and said: “You know what this country reminds me of? It’s got the stuff, the git up and go, and it’s rolling. Why, Turkey today is just like Texas in 1919.”

Both Czar and ambassador had it right. In one century, the sick man of Europe has become the strong man of the Middle East. If not the paradise that propagandists sometimes paint, Turkey is stable, strong, democratic, progressive, booming. No nation stands so steadfast against Russia. In NATO it is the free world’s strong southern anchor; in the Korean war, its brigade was the “BB Brigade,” the Bravest of Brave. Turkish landing fields put U.S. strategic air half an hour away by jet from the Baku oilfields of Russia.

Assisted by U.S. dollars and skill, but doing its own hard work and running its Own show, Turkey is increasing its per Capita income 7% per annum, its gross national product 10%. As recently as 1950, Turkey had to import wheat; today she is the No. 4 wheat exporter in the world. In the same three years, Turkey’s tractors increased by 900%, farm acreage 25%, mileage of all-weather roads 100%, port capacity 250%, cotton output 300%. Yet these are the people of whom the Bulgar peasant used to say, making the sign of the cross: “No grass grows where the Turk’s horse treads.”

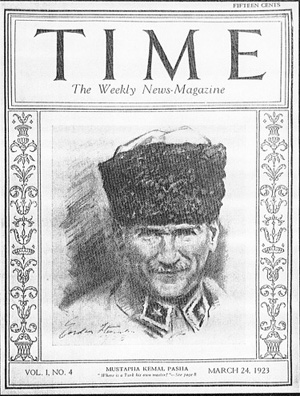

Ruthless Miracle. What brought the change? Between the days of the sick man and the Texas-style Turkey of today, the nation brought forth Kemal Ataturk. He worked his miracle, closed history’s gap in just 15 years, 1923-1938, and died 15 years ago next month.

By conventional standards, Kemal Ataturk was hardly an admirable character. He was a bitter, sullen and ruthless man, a two-fisted drinker and a rake given to shameless debauch. Politically, though he proclaimed a Bill of Rights, he flouted it constantly; though he talked of loyalty, he hanged his closest friends. He was devoid of sentiment and incapable of love, unfaithful to everyone and every cause he adopted save one—Turkey. But before he died, his driven, grateful people thrust on him the last and greatest of his five names: Ataturk, Father of All the Turks.

The Father of All the Turks (who left no legitimate heirs) was born in 1881 in Salonika, then part of the Ottoman Empire, of a mild Albanian father and a forceful Macedonian mother. Mustafa was a rebel from the start. His pious Mohammedan mother urged him to become a holy man, but he became a soldier; at 22, a captain, he rebelled against the Sultan and was nearly executed; at 27, he joined the Young Turks rebellion, then rebelled against the Young Turks. The army, fearful of him, shunted him from post to post, but could neither shake him nor subdue him. At Gallipoli, in 1915, he defeated the British; in the Caucasus, he checked the Russians; in Berlin, 1918, he drunkenly needled the high panjandrum of his allies, Field Marshal von Hindenburg; in Arabia, 1918, he held off T. E. Lawrence’s Bedouin hordes. At 38, he came out of the crash of the Ottoman Empire the only Turkish commander untouched by defeat.

Six Day Marathon. Eight years later, smartly turned out in his favorite civilian attire—the morning coat and striped pants of the Western diplomat—he stood before the Turkish National Assembly (which he created), in the capital at Ankara (which he created), and for six full days told in the Turkish language (which he purified and revised) the full story of what he had done. He began:

“Gentlemen, I landed at Samsun on the 19th of May, 1919. This was the position at the time…”

To his hearers, it was well-remembered history. Turkey in 1919 was crushed, defeated from without, disintegrating within. Gone was the fury and might which, beginning in 1299, had sent Ottoman legions smashing at Vienna’s gates and made Budapest a suburb of Constantinople. Gone was the conquering fervor that created a tri-continental empire the size of the U.S., encompassing what are now 20 modern nations stretching from the Dniester to the Nile, from the Adriatic to the Persian Gulf. In 1919, British warships still rode in the Bosporus and British troops held Constantinople; Italy, France and Greece were secretly dividing up the best of the remainder. The greatest empire between Augustus and Victoria had shrunk to a small, lifeless inland state in the barren interiors of Asia Minor; its Sultan was reduced to the status of a borough president of Constantinople. There was talk of asking Woodrow Wilson to take over the mess as a U.S. mandate.

Mustafa Kemal Pasha returned from his skillful but useless defense of Syria and asked for a job. “Get this man away—anywhere—quickly,” the Sultan cried. The government hoped to save itself by submission to the conqueror; Kemal’s unyielding patriotism endangered these schemes. So Mustafa got magnificent and meaningless titles—Inspector General of the Northern Area and Governor General of the Eastern Provinces—and was put aboard a leaky Black Sea steamer bound for Samsun, in remote Anatolia.

This suited Kemal fine. Arriving in Anatolia, he convoked a congress and proclaimed: “The aim of the movement is to free the Sultan-Caliph from the clutches of the foreign enemy.” Desperately, the Sultan, who did not want to be so freed, wired: “Cease all activity!” Replied Kemal: “I shall stay in Anatolia until the nation wins its independence.” Turkey, or what was left of it, had two governments: Kemal’s and the Sultan’s.

The victorious Allies, of course, favored the complaisant Sultan, but in their greed they served to further Kemal. The Sultan and the Grand Vizier went to Versailles to plead not to be denuded of all land and power. Clemenceau, the Tiger, said coldly: “Be silent, Your Highness! Relieve Paris of your presence.” The Allies handed the Sultan the Treaty of Sevres, which split Turkey six ways. The Greeks marched in to enforce the Diktat, and Kemal roared: “Turks! Will you crawl to these Greeks who were your slaves only yesterday?” He raised an army of peasants, veterans, criminals, patriots. Two years later, a few miles outside of Ankara, he gave the orders: “Soldiers, the Mediterranean is your goal,” and drove the Greeks back into the sea.

The Treaty of Lausanne which followed reversed the humiliation of Sevres. The last British admiral boarded the last British battleship in the Bosporus, snapped a respectful salute to the crescent flag and steamed off. The most defeated of enemies became the first to defy the victorious Allies, to scrap one of their treaties. The Ataturk miracle had begun: Mustafa Kemal, soldier, was master of Turkey.

Only Turks. The nation he put back together was slightly larger than Texas—296,000 sq.mi.—its vast bulk nestled in Asia Minor, with 9,000 sq.mi. wedging into Europe’s southeastern corner. Kemal was satisfied. “We are now Turks—only Turks,” he exulted. He wanted none of the old overextended Ottoman empire. “Away with dreams and shadows; they have cost us dearly,” he said.

Kemal went on a speaking tour among his people: “Remain yourselves, but take from the West that which is indispensable to the life of a developed people. Let science and new ideas come in freely. If you don’t, they will devour you.”

He began taking from the West, but he took with discrimination. He wanted to democratize Turkey, for “no country is free unless it is democratic.” But he recognized that “Democracy in Turkey now would be a caricature,” and set his dictatorship to preparing his nation for democracy. Thirty years ago this month (on Oct. 29, 1923), Kemal became: President of the new republic, commander in chief of the army, president of the Council of Ministers, chief of the only party, and speaker of the Assembly. He began ridding the Turks of the things that reminded them of the degenerate past. First he ordered the Sultan expelled; 16 months later the Caliph (or Moslem spiritual leader) was exiled. Kemal announced that “Islam is a dead thing,” and Turkey became a nondenominational state.

The break with the past had to be felt, simply and simultaneously, by all Turks. Ataturk looked about for the significant gesture. In India it had been salt-making in defiance of the British monopoly; in China it was cutting off the queue. Ataturk chose to attack the fez, traditional symbol of Ottoman citizenship. “The fez is a sign of ignorance,” said he. He laid down a deadline: after that date, no brimless headgear. Some Turks, unable to find hats with brims, wore their wives’ hats: better to look silly than to risk losing your head.

Coffee fo Kahve. Ataturk moved the capital from cosmopolite Constantinople to raw Ankara and changed Constantinople’s name to Istanbul. Though he personally abhorred emancipated women (they argued, instead of saying yes), he begged Turkey’s women to unveil, and most did. He abolished the Moslem sheriat (law) and took the best from Europe to replace it—Switzerland’s civil code, pre-Fascist Italy’s penal code, Germany’s commercial code.

Though he made haste, he had an intuitive awareness of his people’s gait. The old Turkish alphabet had become an esoteric nightmare of cumbersome Arabic scrawls; its difficulty contributed to illiteracy at home and incomprehensibility abroad. Kemal talked first to U.S. Educator John Dewey, then sat down with linguistic experts and worked out a new, simple Latin, A-B-C alphabet of 29 letters. Where new concepts lacked ancient symbols, he simply used Western forms: automobile to otomobil; coffee to kahve; statistic to istatistik.

Blackboards went up in the National Assembly, and Kemal himself gave the Deputies their first lesson. He went to the countryside and guided the gnarled hands of peasants who had never held a pencil before, as they wrote clumsy signatures in the new script. This patient teaching took five years; then abruptly he switched from precept to fiat. He gave civil servants three months to master the new script—or find new jobs. He had not been to Istanbul since 1919; now he returned in style and with a purpose. He sailed into the Golden Horn on the Sultan’s yacht, triumphantly marched past cheering crowds. He summoned Istanbul’s elite to the Sultan’s palace to a ball, and stood before them in full evening dress on a raised platform, chalk in hand, before a blackboard. For two hours he explained the new language, then the music blared, everyone drank, and the dancing went on until dawn. Nineteen twenty-eight became the Year One of Turkey’s new cultural life.

Oy Birligile. Ataturk liberated law, education and marriage from the mullahs; turned mosques into granaries; switched the day of rest from Friday to Sunday; tossed out the Islamic calendar and ordered in the Gregorian calendar of the Western world. He made suffrage universal, adopted the metric system, ordered all Turks to take on last names, took the first census in Turkish history. Harems were forbidden and monogamy became the law.

The most familiar phrase in the Turkish National Assembly during these electric days was Oy Birligile, meaning by unanimous vote. Opposed, Ataturk was ruthless. One evening in 1926, he gave a champagne party for foreign diplomats; it turned into an all-night carousal. Returning home at dawn, the diplomats saw the corpses of the entire opposition leadership, among them Kemal’s old friends, hanging in the town square.

But in his later years, after he had raised his people up, he decided to ease his dictatorship. He brought his ambassador home from France, ordered him to head an opposition, ordered his own sister to join it. The new Liberal Republican Party was so polite at first that Kemal demanded more vigor; when it became more vigorous he abolished it. “Let the people leave politics for the present,” he said. “Let them interest themselves in agriculture and commerce. For ten or 15 years more I must rule.”

After Ataturk. He did not have ten or 15 years more. Since his teens he had been drinking and whoring, searching, without finding, some personal peace. He tried marriage once in 1922 to Latife, the daughter of a Smyrna shipowner, but was soon divorced. In 1938, exhausted by periodic debauches and drinking bouts, undermined by diseases, he died. The timing was just right. Kemal Ataturk had held the Turks by the hand just long enough to help, not long enough to crush.

The day after Ataturk’s death, he was succeeded as President, legally and peacefully, by his handpicked successor, forceful soldier-administrator Ismet Inonu. For the next dozen years, the Inonu regime tried to maintain the Ataturk pattern. The people were kept on short rein, given few civil and personal liberties, and those grudgingly. But the momentum of progress continued.

In 1946, the Ataturk-Inonu party, the Republican People’s Party, won reelection, but only by using shabby tactics. It was the last time. A new, politically conscious opposition had grown up. Ataturk had unleashed forces greater than he; he had made so many new Turks that there was bound to be a new Turkey. In 1950, 88% of the voters went to the polls and swept out the Republican People’s Party which had held power uninterruptedly for 27 years. Inonu yielded gracefully. The newborn Democrats took over.

Their President was unspectacular Celal Bayar, an able banker and one of Ataturk’s ministers for five years, his Premier for one. This peaceful transfer of power was not the millennium, but it was the closest approach to it in the Middle East. Ataturk’s 15 years of ruthless education and preparation had paid off.

“Black Danger.” The new regime put an end to excessive state regulation of business. Ataturk had tried to industrialize Turkey through a cumbersome form of state socialism that he labeled étatisme. He developed some industry, but stifled it in red tape and scared away foreign investors. Now, under Bayar, Turkey is one of the few nations in the world heading towards more, not less free enterprise. Foreign investors are encouraged. There have been other reversals of Ataturk policy. Many emancipated Turks now fear “the black danger,” the resurgence of the once powerful mullahs. Religion is strong today in Turkey. The country is 98% Moslem. Ataturk relaxed the grip of a reactionary and decadent church, but he could not destroy the faith of his people. Just as Ataturk had taken the best from them, discarded the rest, the Turks are showing a talent for preserving what they think best in his teaching.

Turkey today is still far from Ataturk’s goals: 80% of its 21 million people live in mud huts in isolated villages, in half of which there are no primary schools. The currency is soft; inflation has doubled food prices. Much of the land is unfertilized and carelessly utilized. The Turk is poor: he gets a third of the meat that a meat-starved Briton received under austerity; only one in 2,000 owns an automobile. But Turkey’s spirit is good, the country is stable, its directon is sound.

A month hence, Ataturk’s body, which has lain in a “temporary” resting place these past 15 years, will be borne with ceremonial pomp to a new mausoleum on Ankara’s highest hill. The mausoleum, reached by 33 marble steps 132 feet wide, will probably be the biggest of its kind, until Evita Peron’s or the proposed Soviet pantheon tops it. For three days, Turkey’s 21 million citizens will do him honor.

“I will lead my people by the hand along the road until their feet are sure and they know the way,” Ataturk had said. “Then they may choose for themselves and rule themselves. Then my work will be done.” On his bronze statue overlooking the Golden Horn is another message to his people: “Turk! Be proud, hardworking and self-reliant!”

- Find this article at:

-

Turkish Canadian Youth Congress Attracted Great Interest

NOTRE ANATOLIE

TORONTO BUREAUSecond Annual Turkish Canadian Youth Congress was held in Toronto during the weekend of 16, 17 and 18 January, 2009. The Youth Congress organized by Council of Turkish Canadians attracted huge interest, with the attendance of more than 140 participants. Young Turkish Canadians and their friends came to the congress from all across Canada. There were delegates from Vancouver, Halifax, Montreal, Ottawa and Waterloo. A big majority of the youth participated from Toronto.

The congress which took place at the Delta Chelsea Hotel in downtown Toronto, started on 16 January Friday, at 6pm, with a reception. The guest of honour Turkish Ambassador to Canada, Mr. Rafet Akgunay made the opening speech and welcomed the youth to the conference. Mr. Akgunay emphasized the importance of Multiculturalism in Canada, the theme of the conference: “Successful multiculturalism rests on mutual respect; and mutual respect comes from mutual understanding and dialogue.” Mr. Akgunay continued by saying that through the richness of multiculturalism we would be able to improve our collective wisdom. The ambassador also addressed the youth in Turkish and encouraged them to maintain and improve their mother tongue, a definite asset in this age of globalization, which is being spoken by millions of people beyond the borders of Turkey.

The conference continued on Saturday and Sunday, the 17th and 18th of January, with many speaker from academic and political domains. Dr. Umut Uzer and a member of Turkish Coalition of America, lawyer Mr. David Saltzman, came from United States to speak to the youth on Turkish Foreign Policy and Turkish History, respectively. Hon. Dan McTeague, Member of Parliament from Pickering-Scarborough East was among the speakers. Mr. McTeague urged the young Canadians to get involved in politics. One of the stars of the conference was Nil Köksal, a reporter with CBC Morning News. Another young and bright Turkish Canadian, Ayda Eke, an M. A. on Human Rights was a huge hit with the young audience. Public relations expert Gail Haarsma made a presentation on how Canadians view Turkey and Turkish people. Other guest speakers included Demir Delen, Prof. Murat Saatcioglu, Prof. Ozay Mehmet, Hon. Gar Knutson, Dilek Kayaalp, Michael A. Dobbin, Dr. Ertugrul Alp and Yaman Uzumeri.

Throughout the congress, where young people got a chance to meet one another and socialize, the engagement level stayed high and the interaction with the presenters seemed to be the most desired activity. Many delegates, in the evaluation forms, said that they wished for longer Q&A sessions in future conferences. Executive Director of Council of Turkish Canadians, Lale Eskicioglu told Bizim Anadolu that the youth, while being very happy and appreciative of the conference, had not hold back on their constructive criticism in the feedback forms. “Ninety eight percent of them said that they would like to attend future conferences and that they would encourage their friends to do so as well. Seventy three percent said that they would like to participate in organizing future conferences. Then they listed what they want and how they want it. We will listen to them.” said Lale Eskicioglu. “They demand younger presenters and contemporary topics. They want to be a part of the planning as well. This is great news. Next year we will do it together with them. Or rather, they will do it and we will help them.” Lale Eskicioglu concluded by saying that the youth had already started forming a Youth Conference Planning Committee to organize next year’s congress which will take place in Montreal. “We did the first one in Ottawa and the second one in Toronto,” said CTC president Dr. Kevser Taymaz, “It is only natural that the next one should be in Montreal. We hope to take this great event to a different town every year.”

What did the youth say about the Second Turkish Canadian Youth Congress?

– I would like to see more young scholars presenting in future conferences.

– The general atmosphere of the conference was great, perfect location and very good organization.

– The people I met and the topics that were presented were really valuable. I would like to keep in touch with all these people.

– The sessions should be more interactive. Youth should be involved in the organization.

– It was an amazing experience for me. Thank you so much for giving me this opportunity to learn about this wonderful country.

– At the end of the first day of the conference, there should be an organization for the participants that include dinner, music and dance.

– I would like to have more discussions and workshops with people I don’t know.

– The conference was perfectly organized, however, in order to collaborate more with the other Turkish delegates from different cities, there should be more activities that would bring them together. For example, on Saturday night there could be a dinner at a Turkish restaurant.

– I appreciate the fact that there were so many speakers with extraordinary backgrounds and in high positions of different organizations.

– The conference environment was very friendly. Since this is a youth conference there should be more young presenters. Also, I’d like to see more young volunteers.

– In addition to annual conferences, there should be more frequent, local meetings.

February 2009l

-

Guardian Souvenir of the Dardanelles Campaign

November 24, 2010

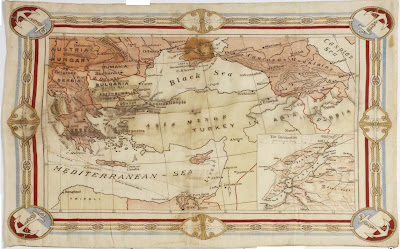

Cloth ‘map’ produced by the Guardian as a souvenir of the Dardanelles campaign. (click to enlarge)

Cloth ‘map’ produced by the Guardian as a souvenir of the Dardanelles campaign. (click to enlarge)

Mavi Boncuk |The Dardanelles has been of great strategic significance for centuries; a narrow 60-mile-long strip of water that runs from the eastern Mediterranean into the Sea of Marmara, it divides Europe from Asia. Carefully secured by international treaty, it was the closing of the Dardanelles that eventually brought the Ottoman Empire into the war as a German ally at the end of October 1914.

Instructions issued to General Sir Ian Hamilton, as commander of military operations at the Dardanelles, by the Secretary of State for War, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener. At Hamilton’s request, the title of the Expeditionary Force was changed to ‘Mediterranean’ from ‘Constantinople’. Although capital of the Ottoman Empire since 1453 and known to the Ottomans as Istanbul, the city remained known in the West by its earlier Christian name of ‘Constantinople’ until the twentieth century.

November 23, 2010

Herbert Hillier in Gallipoli

BONUS: The most popular map download from Mavi Boncuk Archives. A 1915 Gallipoli map printed by the Turkish War Ministry |

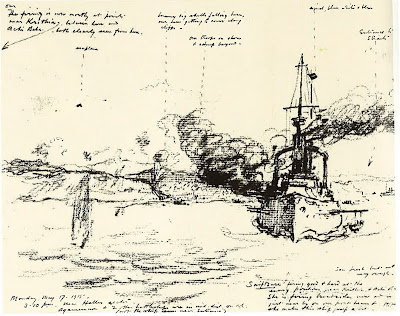

British War Artist Herbert Hillier’s Sketch of may 17, 1915 Salvos from a british ship pound Turkish positions in Gallipoli. Australian War Memorial holds the collection relating to the service of Mr. Herbert Hillier, Royal Navy, Gallipoli, Imbros. Collection consists of typescript copy of a diary kept by Hillier, a British artist, who served in the balloon ship ‘Manica’ [1] off the Anzac position. The diary consists chiefly of notes intended to accompany his sketches made during the Gallipoli campaign. These sketches are held in the Imperial War Museum, London.

Australian War Memorial holds the collection relating to the service of Mr. Herbert Hillier, Royal Navy, Gallipoli, Imbros. Collection consists of typescript copy of a diary kept by Hillier, a British artist, who served in the balloon ship ‘Manica’ [1] off the Anzac position. The diary consists chiefly of notes intended to accompany his sketches made during the Gallipoli campaign. These sketches are held in the Imperial War Museum, London.

The Dawn of Anzac Day, Sunday 25th April 1915, by Herbert Hillier. The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) undertook one of the two major landings of the campaign. 25 April – Anzac Day – is now a day of great significance in both countries, on which the values enshrined in the event are remembered. However, it is also important to remember that the British 29th Division landed on 25 April and suffered comparable casualties.

The Dawn of Anzac Day, Sunday 25th April 1915, by Herbert Hillier. The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) undertook one of the two major landings of the campaign. 25 April – Anzac Day – is now a day of great significance in both countries, on which the values enshrined in the event are remembered. However, it is also important to remember that the British 29th Division landed on 25 April and suffered comparable casualties.

[1] March 11, 1915-The Royal Navy charters the cargo ship SS Manica for conversion into the first British balloon ship, HMS Manica. The Royal Navt will be the only navy during World War I to operate balloon ships, specialized ships designed to handle observation balloons as their sole function. April 19, 1915-During the Gallipoli campaign, the Royal Navy balloon ship Manica lofts her observation balloon operationally for the first time in the first operational use of a balloon ship during World War I. The observer in her balloon directs fire against Ottoman positions for the armored cruiser Bacchante[*]. Manica’s work during the campaign impresses the British Admiralty for it to order additional balloon ships.Photo: A ‘Drachen’ type balloon is held steady aboard the SS MANICA, while its observer waits to climb into the basket, off the Gallipoli coast, summer 1915.

[*]HMS Bacchante was a Cressy-class armoured cruiser launched in 1901 for the Royal Navy. Bacchante served for a while with the Mediterranean Fleet. In 1906 she was transferred to the North America and West Indies Squadron and served there until she returned to home waters. At the outbreak of the First World War, Baccante served as the flagship of the Live Bait Squadron, blockading the English Channel from the North Sea to German traffic. Bacchante took part in the landing at Anzac Cove during the Battle of Gallipoli in 1915. When the infantry came under fire from Turkish artillery at Gaba Tepe, Bacchante approached close in to shore and fired directly on the gun emplacements in an attempt to silence them. -

Taner Akçam, amid contradictions and charges of betrayal, loses credibility

By Ferruh Demirmen, Ph.D.

Taner Akçam, Associate Professor of History at Clark University (Worcester, MA) and the “prince charming” of the Armenian lobby, got himself trapped in contradictions on interpreting the results of Turkey’s recent (September 12) referendum on Constitutional changes. He inadvertently brought to surface some unsavory aspects of his past. Akçam’s younger brother, Cahit Akçam, used the occasion to mock the elder brother and charged him with betrayal.

taner akcam Taner Akçam is an occasional contributor to Turkey’s Taraf, an off-base newspaper that is a staunch supporter of Turkey’s AKP (AK Party, Justice and Development Party). Rumored to be funded by the USA-based Gülen movement, and according to some also by the CIA, it is staffed largely by ex-liberal socialists that are now far to the right. Cahit Akçam is a columnist at Turkey’s left-leaning Birgün newspaper. The AKP is Turkey’s Islamic-rooted ruling party.

What got Taner Akçam into trouble was an op-ed he wrote in Taraf titled “Seeking Milosevic” that attacked Birgün. He took issue with Birgün’s headline news that the referendum had confirmed the 60% right-wing and 40% left-wing split in the country, and that the nationalist conservative votes had consolidated at the AKP. In what was a victory for the AKP, the referendum passed by a margin of 58%.

By drawing an analogy between Birgün and Slobodan Milosevic of ex-Yugoslavia, Akçam implicitly accused the newspaper of supporting nationalistic, racist and genocidal sentiments.

Neighborhood concept

Taner Akçam couldn’t accept Birgün’s view that the 40% of the referendum voters, that had voted “no,” were really left-wing. Noting that mass-killer Slobodan Milosevic, while called a communist and a socialist, had done horrible things, he argued that likewise in Turkey those who voted “no” couldn’t be called true socialists. The naysayers were the main opposition party CHP (Republican People’s Party) and the military-bureaucracy faction. The latter had organized and defended military coups in Turkey, he argued.

According to Akçam, labeling these groups “socialists,” as Birgün did, stemmed from a hatred of the AKP. Akçam called the 40% the “bourgeois group.” He maintained that this hatred is best explained through the “neighborhood” metaphor.

In Akçam’s view, Turkey is founded on “our” and “other” neighborhoods. The first neighborhood is one of “city people” that includes bureaucrats, the military, and the like. The CHP and the Ottoman-era İttihat ve Terakki Partisi (Committee of Union and Progress, CUP) are included in this group.

The “other” neighborhood comprises artisans and peasants that have strong religious identities. This neighborhood is now expanding and encroaching on the “city people” neighborhood.

Akçam sees himself in the “city people” neighborhood, which he calls “ours.”

Contradiction and myopia

But by doing so, Akçam fell into a gasping contradiction, because this is also the group that he labeled “bourgeoisie.” How could someone, with a well-known Marxist background, and calling himself a socialist, be part of the bourgeois group? (Separate from his self-confessed connection to the terrorist PKK organization during 1981-84, Akçam escaped from Turkish prison in 1977 after having been convicted of left-wing terrorist activities aimed at, among others, NATO military and American personnel).

Surprisingly enough, Akçam supports the “other” neighborhood – the conservative, Islamic group solidly backed by Taraf. This is because he thinks this group has strong democratic credentials.

It doesn’t take a professor’s prescience to know that such an argument is plain vacuous.

With the AKP in control – political lords of the 60% group – Turkey today is far removed from democracy – the illegal wiretappings, indefinite detentions and imprisonment of the opponents (including 47 journalists) of the government, an atmosphere of fear permeating the country, mandatory religious education, widespread penetration of Gülenist elements in the state apparatus, in particular the police, appalling inequality between men and women, systematic efforts (re: the referendum) to bring the judiciary under the control of the government, parliamentary immunity, etc. None of these inequities seems to bother the professor.

In Turkey today the press is under siege, and by Prime Minister’s own admission, “Those that are impartial [to the AKP] should be eliminated.” There are more detainees in prison than those convicted. Many detained under the so-called “Ergenekon case” don’t even know the exact charges against them.

No scruples, and no loyalty

Akçam’s contradictions and distortions also caught the attention of his younger brother Cahit Akçam. Responding to the elder Akçam in Birgün, Cahit Akçam couldn’t hide his scorn. In a blistering, two-part rebuttal titled “Really, you are the child of which neighborhood?” he chastised his brother, and mockingly called on him to come to his senses. His article started with a quotation (and an admonition) from Anton Chekhov: “Others’ sins do not make you a saint.”

Cahit Akçam called the elder Akçam’s “our” vs. “other” neighborhood analysis, with “Marxist-smelling” questions, “light” and meaningless because it was not founded on class distinction. Neither neighborhood as described by Taner embraced the working class. Asking the rhetorical question as to how Taner could overlook the working class, the younger Akçam thought that his brother, in what appeared to be sheer hypocrisy, didn’t really care for the working class.

Continued the younger brother sarcastically: “Luckily, Taner at least didn’t ignore the bourgeois class in ‘our’ neighborhood.” He chaffed at his brother for not mentioning the bourgeois class in the “other” neighborhood, i.e., the Islamist businessmen that the Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan had braggingly called “The Anatolian Tigers.”

Wondering how his brother could not know that the bourgeois class cannot exist without a working class, Cahit mocked his brother: “He is a big professor. True, not a sociology professor, but a history professor nonetheless. He has licked and swallowed a thousand times more than we have. He knows that, to be so ignorant, one does not have to be a professor. For Taner, the working class has little value.”

The elder Akçam was tersely reminded of the struggles of Turkey’s working class since 1900.

Cahit continued his criticism by making reference to a Turkish metaphor – referring to lentil meal – that this is all that the Taner could muster as an argument. Referring to Taner’s claim that all the “infamous” events in Turkey’s history emanated from “our” class, he bristled at Taner’s suggestion that the socialists, through the CHP, were like relatives to the military- bureaucracy.

He mockingly called attention to the fact that the socialists had suffered immensely from the 1980 fascistic military coup.

Recalling how the elder Akçam had defended the causes of right-wing, fascist elements in Turkey’s recent history, how he had failed to come to the defense of socialists who had been falsely accused of coup attempts, his denialist past, and how he had let down even his own family, the younger Akçam weighed in angrily: “How can Taner accuse his old friends, and even his own brother, as potential perpetrators of genocide?”

Barely concealing his disdain, Cahit asked of his brother: “As you place the blame on your own neighborhood, can there be a more harrowing psychological ruin [for you]? … Where is your heart, and your conscience?”

The ultimate indignity came when the younger Akçam concluded that only someone who was politically and ideologically blind, and someone who had lost his scruples and his sense of loyalty, could do what his brother had done.

In the background of such emotional outburst was the fact that, while Taner Akçam jumped the prison in 1977 into the safety of Germany and escaped the tribulations of the 1980 military coup, in the coup’s aftermath his brother was put on trial for unauthorized activities, faced death by hanging, and was imprisoned for 8 years. Obviously, a lecture on fascism and the struggles of socialists was the last thing the younger Akçam wanted to hear from a sibling he considered unscruppled and untrustworthy.

A revisionist professor

There was more to Akçam’s false accusations. He twisted history and put finger on “our neighborhood’ as the perpetrator of the May 27 (1960), March 12 (1971) and – obliquely – September 12 (1980) military interventions in Turkey. Evidently to hide his own past, and the embarrassment therewith, in his accounting he glossed over the 1980 military coup and the events (including his role) that preceded it.

He dallied further into the past and noted that his “neighborhood” was also responsible for the so-called “Armenian genocide” and the Dersim events (1937).

But he was quick to disown any blame – a point that also drew ridicule from the younger Akçam. Instead, Taner Akçam conveniently placed the blame on “our administrators.” Socialists like him, while closely affiliated with the administrators, had deep disagreements with them. It was all the fault of the administrators, not the socialists like him, he argued.

Nice scapegoat, these administrators were! All that exonerated Akçam and made him squeaky clean!

As to why “we socialists” never faced up to the criminal acts in Turkish history, Akçam argued that animosity toward the “other” neighborhood was far more important than facing up to criminal acts. “Our culture was such that we [preferred to] blame the Armenians for cooperating with the imperialists while we were fighting our war of independence, and the Dersimians represented a backward and feudal system.”

Then Akçam made his grandstand by calling on “our” neighborhood to face up to its crimes.

In such argumentation Akçam conveniently dismissed the criminality of the Armenian gangs in the massacre of more than a half-million Moslems, the fatal blow that the Armenian rebellion had inflicted on the fighting ability of the Ottoman armies in wartime, and ignored the fact the Dersim episode was instigated by reactionary feudal lords that had conspired against the young Turkish republic.

Akçam also chose not to mention the bloody 1993 Madimak episode in the Anatolian city of Sivas. A crowd of fanatic Islamists (from the “other” neighborhood), amid chants of “Allah-ü Ekber,” set fire to a hotel where a group of left-leaning intellectuals had assembled. In the ensuing mayhem 37 artists and writers lost their lives.

Akçam’s analysis of past events is the hallmark of an academician who follows a one-track, necessarily biased, approach to historical events.

In his call to confront one’s criminal history, Akçam should turn the tables and first ask the Armenians and “other” neighborhood to confront their criminality. Why, for example, are the Armenian archives in Yerevan and Boston closed while all Turkish ones open? What are the Armenians hiding?

And when will the likes of the “Madimak crowd” see the light of Enlightenment?

Summing it up

The Taraf-Birgün episode raised the specter of a history professor who, by the reckoning of his own brother, was long in false accusations but short in scruples and trustworthiness. The episode also caught the professor in contradictions and brought to light his biased, one-track approach to traumatic events in Turkish history in the past 100 years.

Will all this make any difference as regards Akçam’s credibility as a scholar for the Armenian money masters who sponsor his academic career – like the Zoryan Institute and the Cafesjian Family Foundation when Akçam was at the University of Minnesota, and now the Arams, the Kaloosdians and the Mugars at Clark University? Considering that the professor’s criminal past has so far made no difference, the answer must be a firm “no.” Obviously, the professor is serving a useful – in fact very useful – purpose for the Armenian lobby.

It must be a wondrous world when the “golden” Armenian coffers can sustain an academic chair in history when, as in Akçam’s case, the holder of that chair happens to have his degree in sociology.

In fact, we should not be too surprised if the spinmasters of the Armenian lobby call on their “prince charming” to come to the aid of the Armenian mob charged last month with the largest Medicare fraud in U.S. history. Could the professor argue that the mob job was actually the “dirty work” of the Turks? Never say “no.”

To rephrase his brother’s question, in which “neighborhood” does Taner Akçam stand when it comes to truth?

Surely, the professor must be able to answer that question himself without help from his old-time mentor, Professor Vahakn Dadrian.

A deeper question is, why Akçam-the-professor would write in a newspaper such as Taraf which has a reputation of acting as a rogue agent of the government on unsubstantiated allegations relating to the opposition, and whose executive editor, Ahmet Altan, in his own words, would be willing to sell out his country “for a woman’s breast and the shade of a cherry tree.” …. But that would be a different story.

Addendum: The above article was first submitted (as an exception) to “Armenian Genocide Resource Center,” . Initially, the host welcomed the article and published it as an “exclusive” on its website. Half a day later the post was mysteriously removed from the website. Query as to why it was removed elicited no satisfactory response.