Every morning Yasemin Derbaz puts on the piece of cloth that marks her out as an observant Muslim.

Millions of other Turkish women do the same: it is estimated that at least 60% cover their heads.

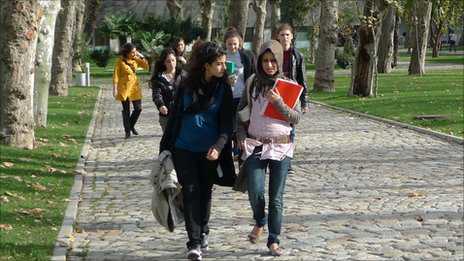

Now, for the first time, almost all universities across Turkey have abandoned the official prohibition on women wearing headscarves.

The ban ended when the government issued a statement in September saying it would support any student expelled or disciplined for covering her head.

“Start Quote

I feel happy that I don’t have to stop in a mosque on the way and change into my wig”

End Quote Yasemin Derbaz

The Islamic headscarf has become a divisive symbol, which bars women from jobs and education, and came close to bringing down a government two years ago.

Yasemin can now go to her architecture classes at Yildiz Technical University for the first time without wearing a large hat or a wig to cover her hair.

“I feel happy that I don’t have to stop in a mosque on the way and change into my wig,” she said.

The exact status of the headscarf ban is mired in confusion.

There is no law against wearing one. Nor does the ban originate with modern Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, although he did discourage women from covering their heads, and passed a law barring men from wearing traditional Ottoman clothing.

Emine Erdogan was blocked from entering a military hospital in 2007 for not removing her headscarf

Emine Erdogan was blocked from entering a military hospital in 2007 for not removing her headscarfThe more recent ban on headscarves in universities and for public servants dates back to regulations passed by government departments in the 1980s, after the last military coup.

With leftist groups harshly suppressed, Islamic parties made strong gains among the Turkish electorate in the elections that followed, prompting a reaction from the avowedly secular military.

The university ban was only properly enforced after the military forced out an overtly Islamic prime minister in 1998.

What the regulations had in mind was not the traditional scarf, tied around the neck by peasant women in Anatolia, but the hijab, also called a turban in Turkey, which has become a symbol of pious or political Islam, worn by growing numbers of urban, educated women since the 1980s.

It is for that reason that military buildings will allow headscarfed women in if they take out the pin that holds the tightly-wound hijab in place – they have a special pin-box at reception.

“Start Quote

The state should be impartial to race, religion, everything”

End Quote Hursit Gunes Opposition CHP party

Emine Erdogan, the wife of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, was blocked from entering a military hospital in 2007 for refusing to remove hers.

Mr Erdogan tried to overturn the university ban in 2008, through a constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right to education.

It passed through parliament, but was thrown out by the Constitutional Court.

But this year, with the momentum behind him after winning the constitutional referendum in September and more compliant bureaucrats in the Board of Education, the government in effect ended the ban by stealth.

The Constitutional Court is in any case being restructured following the referendum, and is less likely to challenge the governing party so boldly in future.

Caught off-guard

The main opposition party, the secular CHP – previously a strong supporter of the university ban – wanted to negotiate its end with the government, but was denied the chance.

Lawyer Fatma Benli says that her headscarf bars her from appearing in court

Lawyer Fatma Benli says that her headscarf bars her from appearing in courtBut the party has vowed to maintain the ban on civil servants wearing headscarves.

“The reason why we don’t allow a headscarf for, say a judge, is that it is a symbol of religion. The state should be impartial to race, religion, everything,” says Hursit Gunes, a deputy secretary-general of the party.

There are still academics appalled by the prospect of headscarves on campus.

“Universities are supposed to be places where science and scientific thought can be discussed freely,” says Nezhun Goren, a biology professor at Yildiz Technical University.

“Religious faith can’t be discussed, you either accept it or reject it.”

Disadvantaged

The resistance to headscarves among many secular Turks seems to be driven by something deeper – a belief that the rigorous adherence to Islam it symbolises in the wearer will eventually reverse the modernisation of Turkish society under its strictly secular system.

Lawyers are still barred from wearing the headscarf in court

Lawyers are still barred from wearing the headscarf in courtHeadscarfed women say right now they are the ones who are disadvantaged.

Fatma Benli is an experienced lawyer who specialises in defending women. But her headscarf bars her from appearing in court – she has to appoint bare-headed proxies to defend her clients.

“For 12 years I’ve been working long hours as a lawyer and I have specialist skills, in international law, so I should be well-paid,” she says, “yet I still have to rely on financial help from my parents to run my office”.

Dilek Cindoglu, a sociologist at Bilkent University who does not wear a headscarf, has done research which shows that the restrictions on headscarfed women in the civil service have spilled over into the private sector.

“Once they get employment they are being discriminated against in terms of promotions, salaries, and in terms of dismissals should the company decide to reduce the workforce.”

I asked Yasemin if she understood the fear many secular Turks feel about openly pious Muslims like herself.

“I am forcing myself, but I cannot say that I totally understand it.”

She argues that she was the one left with the psychology of fear, not them, because for 10 years she was unable to go to school wearing her headscarf.