-I no longer recognize Turkey, the country where I was raised and spend most of my time when I am not teaching in the U.S.

MAKALENİN İNGİLİZCESİ VE TURKCESİ ASAGİDADİR

PULAT TACAR, TURKISHFORUM DANISMA KURULU, BUYUKELCI(E)

The Death of Turkey’s Democracy

“I no longer recognize the country where I was raised.”

By DANI RODRIK

I no longer recognize Turkey, the country where I was raised and spend most of my time when I am not teaching in the U.S.

It wasn’t so long ago that the country seemed to be taking significant strides in the direction of human rights and democracy. During its first term in government, between 2002 and 2007, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) worked hard to bring the country into the European Union, to reform its legal regime, and to relax restrictions on Kurds.

But more recently, the same government has been responsible for a politics of deception, dirty tricks, fear, and intimidation that couldn’t present a sharper contrast to its rhetoric on democracy. Several Turkish intellectuals abroad who have expressed critical views have told me they are afraid to return to Turkey. Eavesdropping has reached such levels that even housewives refrain from chatting about “sensitive” matters on the phone.

The AKP government has launched massive, politically motivated court cases against its opponents. Most glaring are the hundreds of current and retired military officers, lawyers, academics, and journalists who have been charged with membership in an armed terror organization, dubbed “Ergenekon,” which aims to destabilize and topple the AKP government.

Associated Press

Ultra-nationalist supporters holding a banner identifying the “real” villain in the Ergenekon affair: “The plot will be foiled, America will lose, Turkey will win.”

Pursued by a group of specially appointed prosecutors, and loudly cheered by AKP-friendly and AKP-controlled media, these Ergenekon trials make a mockery of due process. They are based on indictments full of inconsistencies, rely on anonymous informants of questionable credibility, and evince systematic prosecutorial misconduct. The evidence behind the charges ranges from the insubstantial to the blatantly manufactured. The main purpose of the prosecutions seems to be to discredit the accused and keep them under detention for as long as possible.

My personal wake-up call came in February when retired General Cetin Dogan, my father in law, was arrested in a parallel case. Mr. Dogan, an outspoken critic of the AKP, was charged with being the leader of an elaborate coup plot to overthrow the newly elected government in 2002-2003. The documents backing the charges, produced as usual by an anonymous informant, were full of anachronisms, discrepancies, and mistakes, raising serious questions about their authenticity. None of this derailed the government. Prosecutors ignored all indications of forgery, a government-controlled scientific body produced a patently misleading report lending support to the charges, and the pro-AKP media launched a vicious campaign of character assassination against Mr. Dogan. Mr. Erdogan and his circle joined in the chorus of attacks while denigrating judges that would dare rule in favor of the defendants. Mr. Dogan was kept for months in jail pending trial, along with tens of other active-duty and retired officers, despite the absence of credible evidence and obvious signs of fabrication.

Inexplicably, many supposed Turkish democrats and liberals have made common cause with the AKP government and have acted as cheerleaders for these cases. Their hope seems to be that the Ergenekon trials will bring the so-called “deep state”—clandestine networks of the military and their civilian allies—to account. There is little doubt that Turkey’s pre-AKP secular order featured strong anti-democratic undercurrents. But the AKP government has shown little interest in uncovering actual crimes or bringing real culprits to justice. Even though some of the Ergenekon suspects may be guilty of transgressions, they have been indicted not for specific, demonstrable offences, but for nebulous or fictitious crimes unlikely to result in convictions in a fair trial. Moreover, in these and other cases the government engages in exactly the kinds of activities that the liberals decry and want to bring to justice.

Consider some other examples. Despite considerable evidence that senior members of the police were, at a minimum, guilty of gross negligence in the murder of the Armenian journalist Hrant Dink in January 2007, none of the policemen have been prosecuted. It is not a coincidence that some of these same police officials have led the Ergenekon investigations. A distinguished chief state prosecutor has been imprisoned on trumped-up charges of being a member of the Ergenekon network, even though he was one of the few prosecutors courageous enough to go after the military gendarmerie’s intelligence branch, a stronghold of the deep state, during 1998-1999. His real crime: Investigating religious orders connected to the AKP. Despite clear indications that the police and prosecutors have been involved in the planting of or tampering with evidence against Ergenekon suspects, there have been no attempts to explain, let alone investigate, the misconduct.

Given the trail of wrongdoings the AKP is leaving behind, it will likely do whatever it takes to avoid losing power in next summer’s elections. Sadly, Mr. Erdogan’s inclination will be to raise the temperature a few notches higher, both domestically and internationally (see its recent rapprochement with Iran, or its brinkmanship against its old friend Israel).

It’s clear now that Turkey is no longer the liberalizing, emerging democracy under the AKP that it was only a few years ago. It’s time the U.S. and Europe stopped treating it as such—both for their own sakes, and for the sake of the Turkish people.

-Mr. Rodrik is the Rafiq Hariri professor of International Political Economy at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

*******************************************************

Türkiye Demokrasisinin Ölümü

DANI RODRIK, Harvard Üniversitesi Uluslararası Siyasi Ekonomi Bölümü Profesörü.

İngilizceden çeviren: Çimen Turunç Baturalp (The Wall Street Journal)

Büyüdüğüm ve Amerika’daki hocalığımdan arta kalan bütün zamanımı geçirdiğim ülkeyi, Türkiye’yi artık tanıyamıyorum. Ülkenin demokrasi ve insan haklarında dev adımlarla ilerliyor gibi görünmesinin üzerinden çok fazla zaman geçmedi. Hükümetin 2002 ile 2007 yılları arasındaki ilk döneminde Başbakan Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’ın Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP) ülkeyi AB’ye götürebilmek ve Kürtler üzerindeki kısıtlamaları gevşetebilmek için çalışmıştı.

Ama son zamanlarda aynı hükümet kendi demokrasi söylemi karşısında bundan daha keskin bir zıtlık sergileyemeyeceği ölçüdeki kirli oyunların, korku ve sindirme politikalarının sorumlusu haline geldi.

Eleştirel görüşlerini açıkça ifade etmiş olan yurtdışındaki birçok Türk entelektüeli bana Türkiye’ye dönmekten korktuklarını söylüyorlar. Gizli dinlemeler öyle boyutlara ulaşmış ki ev kadınları bile telefonda “hassas” konularda sohbet etmeye çekinir olmuşlar.

AKP hükümeti muhaliflerine karşı çok sayıda, siyasi motivasyonlu dava başlattı. En çok göze batan davalılar “Ergenekon” adı verilen ve ülkeyi karıştırarak AKP hükümetinin düşmesini sağlamak amacıyla kurulmuş silahlı bir terör örgütünün üyesi oldukları iddiası ile suçlanan yüzlerce emekli ve muvazzaf subay, avukat, akademisyen ve gazeteci oldu. Özel olarak atanmış bir grup savcı tarafından yürütülen ve AKP dostu, AKP tarafından kontrol edilen bir medyanın sevinç çığlıkları ile desteklenen bu Ergenekon davaları asıl süreçle alay etmektedir. Bu davalar genellikle tutarsızlıklarla dolu ithamlara dayanmakta, güvenilirlikleri tartışmalı adı meçhul ihbarcılara inanıldığını ve sistematik savcılık suiistimallerinin varlığını ortaya çıkarmaktadır. Suçlamaların dayandırıldığı kanıtlar, hayali olanından kabaca kurgulanılanına kadar gider. Savcılığın asıl amacı sanki itham edilenlerin itibarını düşürmek ve onları mümkün olduğu kadar uzunca bir süre gözaltında tutabilmektir.

Çetin Doğan hakkındaki suçlamalar

Beni kişisel olarak uyandıran alarm, şubat ayında kayınpederim, emekli Orgeneral Çetin Doğan, paralel bir dava için tutuklandığında çaldı. AKP’ye karşı sesi gür çıkan bir muhalif olan Doğan, 2002-2003 yılında yeni seçilmiş hükümeti devirmek için özenle hazırlanmış bir darbe planının lideri olmakla suçlanıyordu. Suçlamalara temel olan belgeler, her zaman olduğu gibi adı meçhul bir ihbarcı tarafından üretilmiş, orijinalliğine ilişkin ciddi kuşkular uyandıran zamanlama hataları, çelişkiler ve yanlışlarla doluydu. Bunların hiçbiri hükümeti yolundan çevirmedi. Savcılar sahteciliğin tüm belirtilerini görmezden geldiler, hükümetin kontrolündeki bilimsel bir kuruluş suçlamalara destek veren açıkça yanıltıcı bir rapor üretti. Ve AKP yanlısı medya, Doğan’a karşı çirkin bir karalama kampanyası başlattı. Erdoğan ve çevresi bir yandan sanıkların lehine karar almaya cesaret edebilen hâkimlere iftiralar atarken bir yandan da saldırılar korosuna katıldı. Doğan, mahkemeyi beklerken onlarca muvazzaf ve emekli askerle birlikte, güvenilir deliller olmamasına ve sahteciliğin açık işaretlerine rağmen aylarca hapishane de tutuldu. Anlaşılmaz bir biçimde bu mesele birçok sözde Türk demokratı ve liberalinin ortak davası haline geldi ve bu insanlar bu davaların amigoluğunu yapar oldular. Herhalde Ergenekon davalarının derin devlete, yani ordu ve sivil müttefiklerinin kurduğu gizli ağlara hesap soracağı ümidini taşıyorlardı. Türkiye’nin AKP öncesi laik düzeninin güçlü antidemokratik eğilimlerin işaretlerine sahip olduğuna dair pek kuşku yoktur. Ama AKP hükümeti asıl suçların ortaya çıkarılması ve gerçek suçluların adaletin önüne getirilmesi konusuna pek fazla ilgi göstermedi. Bazı Ergenekon zanlıları ihlallerden dolayı suçlu da olabilirler. Ama bu kişilerin somut, kanıtlanabilir suçlar yerine, bulanık, kurmaca suçlarla itham edilmeleri adil bir mahkeme sonucuna ulaşma olasılığını yok etmektedir.

Dahası hükümetin kendisi bu ve diğer davalarda, liberallerin lanetlediği ve yargının önüne getirmek istediği türden faaliyetlerin tıpatıp aynısına girişmiştir. Başka örneklere bakalım. Yüksek rütbeli polislerin Ermeni gazeteci Hrant Dink’in Ocak 2007’de öldürülmesi olayında en azından, büyük ölçüde ihmallerinin olduğuna dair hatırı sayılır miktarda kanıt bulunmasına rağmen bu polislerin hiçbiri yargılanmadı. Aynı polislerin bazılarının Ergenekon soruşturmasını da yürütmüş olmaları bir tesadüf değildir. Saygın bir cumhuriyet savcısı, uydurma suçlamalara dayanılarak Ergenekon ağı üyesi olduğu iddiasıyla tutuklandı. Bu savcı 1998-1999 arasında derin devletin kalesi sayılan jandarma haberalma dairesinin üstüne gitmeye cesaret gösterebilen çok az sayıda savcıdan biriydi. Gerçek suçu, AKP ile bağlantısı olan tarikatları soruşturmaktı. Polis ve savcıların Ergenekon sanıkları aleyhine kanıtlarla oynanmasına karıştıklarını gösteren somut işaretler olduğu halde görevini kötüye kullanılmasına ilişkin, bırakın bir soruşturma yapılmasını, herhangi bir açıklama bile gelmedi.

Geride bıraktığı haksızlıkların izlerine bakılarak gelecek yaz yapılacak seçimlerde AKP’nin gücünü kaybetmemek için elinden geleni ardına bırakmayacağı söylenilebilir. Ne yazık ki Erdoğan’ın eğilimi hem iç hem de dış siyasette harareti birkaç derece arttırmak yönünde olacaktır. (Son günlerde İran’la yakınlaşması veya eski dostu İsrail’e karşı gerilim politikası.)

Şu açıktır ki Türkiye artık daha birkaç yıl önce AKP yönetiminde liberalleşen, gelişen demokrasi değil. Artık ABD’nin de Avrupa’nın da ona sanki öyleymiş gibi davranmaktan vazgeçmesinin zamanı geldi. Hem kendi hem de Türk halkının selameti adına…

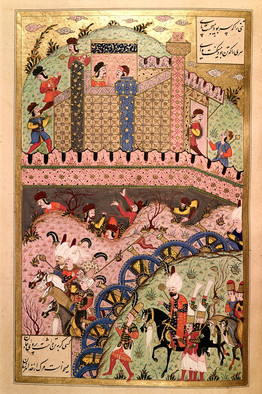

![Ottoman Past Shadows Turkish Present 5 [turkey]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PT-AP092_turkey_DV_20100625184639.jpg) The Bridgeman Art Library‘The Conquest of Belgrade by Sultan Suleyman I,’ a 16th-century depiction of an Ottoman victory.

The Bridgeman Art Library‘The Conquest of Belgrade by Sultan Suleyman I,’ a 16th-century depiction of an Ottoman victory.

![Ottoman Past Shadows Turkish Present 6 [turkey]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PT-AP093_turkey_DV_20100625184755.jpg) AlamyMustafa Kemal Atatürk.

AlamyMustafa Kemal Atatürk.

![Ottoman Past Shadows Turkish Present 7 [TURKEY]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PT-AP141_TURKEY_DV_20100625191019.jpg) The Bridgeman Art LibrarySultan Bayezid II, who welcomed Jews exiled from Spain.

The Bridgeman Art LibrarySultan Bayezid II, who welcomed Jews exiled from Spain.