The Golden Horn is booming as the world’s most dynamic city transforms its skyline and artists and students help make it buzz

In the run-up to New Year, the tourists were haggling over Louis Vuitton and Prada rip-offs in Istanbul‘s fabled grand bazaar. But in the high-rise shopping centres on the other side of town, bargain hunters in the winter sales are battling to get their hands on the real thing.

Istanbul’s covered market, an early shrine to shopaholism, is about to celebrate its 550th anniversary with a multimillion-pound facelift. In fact, the entire city is in the throes of a multibillion-pound makeover, as what was once an outpost on the edge of Europe rebrands itself as a regional magnet.

The city is buzzing. Only a few years ago, when residents spoke of millennium domes it was not the O2 venue for the latest Lady Gaga concert they had in mind, but the thousand years separating the Church of Hagia Sofia and the Blue Mosque on the skyline of the city’s historic peninsula. But now there are new skylines. At the European entrance to the Bosphorus bridge, work goes on through the night on the Zorlu Centre, a hotel-arts-shopping-residential-office complex. It is just down the road from the Sapphire skyscraper, which advertises itself as Istanbul’s tallest building, and with a strong arm you could throw a stone at the new Trump Towers.

“Istanbul is a country, not a city,” says its mayor, Kadir Topbas, and the explanation of its modern boom is buried in the history of the past 30 years. In 1980 Istanbul could not afford the electricity to illuminate that famous skyline. The city, along with the rest of Turkey, was under martial law and there were midnight curfews and even shortages of Turkish coffee.

Since then the city has elbowed its way into the global economy. The backstreet clip joints in the European neighbourhood of Beyoglu have turned into boutique hotels, fusion eateries and world music clubs. The smoke-filled coffee houses whose patrons once scrounged for the price of a glass of tea, now serve lattes – and if you try to light up, there is a £30 fine.

At the end of the second world war, when the iron curtain came down to isolate Istanbul from the rest of Europe, only a million people lived here. Since then, the city has increased its population by that amount every 10 years. “Today’s Istanbul is above all an immigrant city,” says Murat Guvenc, city planner and curator of Istanbul 1910-2010, a remarkable exhibition that explains the pace of change. It is housed in santralistanbul – a converted power station more brutally chic than London’s Tate Modern.

Turkey is already a young country – the average age is 29 – but Istanbul is even younger. People come there to work and often retire somewhere else. And if Turkey is notoriously poor at getting women into formal employment, nearly half of them work in Istanbul.

A recent study by the Washington-based Brookings Institution, in a joint investigation with the LSE Cities project, judged that Istanbul had beaten Beijing and Shanghai to claim the title of 2010’s most dynamic city.

“Istanbul takes the top ranking for economic growth in the past year,” wrote Alan Berube, director of the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Programme. “Its economy expanded by 5.5% on a per capita basis, and employment rose an astonishing 7.3% between 2009 and 2010. Turkey’s banking sector, which was less invested in risky financial instruments, became a safe haven for global capital fleeing established (and exposed) markets during the downturn.”

Economists may be just realising that Istanbul is the place to be. Couch surfers and Erasmus exchange students have known this for some time. If emerging markets are kick-starting the global economy, creative dynamism is ebbing away from the old centres to the new. Istanbul is fast resembling Henry Miller’s Paris or the post-Soviet city-wide party in Prague where western twentysomethings can spend that critical time between university and life. “You just can’t just show up in New York or London and hope to fit in,” says Katherine Ammirati, 23, from Berkeley, California. “At least not without a plan bankrolled by well-heeled parents.”

She came to Istanbul, doing tutoring jobs and then clerical work at a law firm and will go home one day to become a lawyer herself. “Istanbul still has rich and poor side by side, and that makes it feel like a real city,” she says.

The international art community, too, has put the city on its nomadic route, drawn in large measure by the success of the privately organisedIstanbul Biennial, which will be held again this September. Sotheby’s recently set up shop in Istanbul, motivated by a new generation of Turkish artists and the new purchasing power of Turkish patrons. In the opening-night crush at Contemporary Istanbul, the city’s late autumn art fair, there was hardly elbow room to lift a glass.

The frontiers are disappearing. New York galleries are opening up in Istanbul and Turkish collectors go abroad. Art Basel Miami Beach might not feel the competition yet, but the city founded by Constantine as the new Rome in 330 wasn’t built in a day.

“Istanbul’s biggest problem is that we don’t know what we’re doing right,” says Kasim Zoto, a hotel keeper who sits on the board of the Turkish Hotel Association. In 1955 a Hilton hotel opened up a new modernist skyline across from the Golden Horn and the hillside was soon littered with convention centres, concert halls and more five-star hotels. In the next two years, the number of hotel rooms in the city will rise by a third and two new Hiltons will open.

Not everyone approves of the consequences of such vertiginous growth. To some, gentrification appears out of control as “real” neighbourhoods, whether those of the Roma community by the old city walls, or the working-class districts around Beyoglu, are bulldozed for redevelopment. Only high-level lobbying last year stopped the city from being defrocked by Unesco as a world heritage site, as a row blew up over plans for an overland rail link for the city’s metro system that would slice the view of the Suleymaniye Mosque.

The city has so far failed to meet an undertaking to produce an inventory of historic buildings and a master plan to manage the peninsula – all measures that would get in the way of the developers’ axe. Environmentalists feel powerless to stop the construction of a third Bosphorus bridge which, if the precedents of bridges one and two are anything to go by, will lead to the destruction of the city’s remaining green belt.

Optimists and pessimists over Istanbul’s future tend to be divided along political lines, according to Hakan Yilmaz, a political scientist at the city’s Bosphorus University.

Those who support the current religious-leaning government are inclined to see the glass half full. It is Turkey’s ardent secularists, now losing their status, who feel less hopeful about the future.

And while some Istanbulites might see themselves caught up in a clash of civilisations, between the pious and religious and a western-oriented elite, for others it is precisely this tension that makes the city come alive.

“There is a new culture being born,” says Kutlug Ataman, a Turner prize finalist. The “usual suspects” – the food and the nightlife – are what make Istanbul such an attractive place, he argues, but it’s the pace of change that makes the city so addictive. Having fled the country after the 1980 military coup, he sees Turkey’s transformation evolving, however imperfectly, in the right direction.

As if to make his point, alongside a retrospective of Ataman’s own work in the Istanbul Modern museum is a celebration of the contribution of Armenian architects to the 19th and early 20th century city, an important step in allowing the city’s remaining Armenian community to reclaim the space they created. “We are becoming more democratic and you feel as an artist that you can make an impact,” Ataman says.

And if Istanbul feels despondent about surrendering its European capital of culture crown to Turku in Finland, it knows the cloud has a silver lining. In 2012, it will become European capital of sport.

Andrew Finkel is the author of the forthcoming book Turkey: What Everyone Needs to Know, published by OUP

URBAN RENEWAL

667 BC City of Byzantium established by Greek colonists from Megara. Named after their king Byzas.

AD 73 Byzantium incorporated into the Roman Empire.

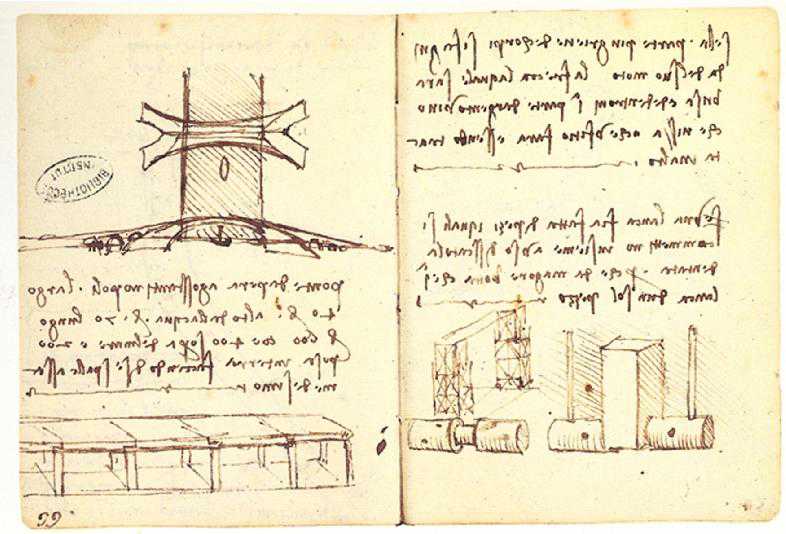

330 Byzantium becomes the capital city of the Roman Empire and is renamed Constantinople after the Emperor Constantine, pictured.

1453 Constantinople captured by the Ottoman Turks, who call it Istanbul after the Greek meaning “to the city”.

1923 Upon the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, the capital city is moved from Istanbul to Ankara.

1930 Constantinople is officially renamed Istanbul.

2010 Istanbul named as one of the European capitals of culture.

The Guardian