Locating Turkey among the G20 Rising Powers in the South-South Development Cooperation

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Emel Parlar DAL Marmara University

Dr. Samiratou DIPAMA Marmara University

This study aims to assess how Turkey has been located among the G20’s rising donors who have been actively engaged in the South-South Development Cooperation (SSDC). In doing so, it aims to compare Turkey’s and the selected G20 rising donors’ bilateral, multilateral, geographical and sectoral aid distribution by using OECD ODA Data, UN ECOSOC’s Quadrennial Comprehensive Policy Review (QCPR), Aid data statistics and the relevant countries’ domestic development aid data. First, the study will try to explain the actorness of Turkey in the sphere of South-South Development Cooperation and question its role as a Southern donor. Second, it will compare the performance of Turkey’s rising donor status in terms of bilateral-multilateral, geographical and sectoral distribution of aid with that of other G20 rising donors. In the final analysis, it will present the weaknesses and the strengths of Turkey in the field of SSDC compared to its G20 peers.

Keywords: Turkey, G20 rising donors, ODA, South-South Development Cooperation, bilateral-multilateral aid.

INTRODUCTION

The US-led world order established in the post-Cold war era is currently going through deep challenges with the rise of new powers from the global south with significant material capabilities. These new types of rising powers including among other countries such as China, India, Brazil, and Turkey have been at the core of the global shift of power. Although these rising powers have been active in almost all global issues, one of the most important domains where they seem to have been more assertive is development cooperation. Most of these emerging donors promote South- South development Cooperation (SSDC) as an alternative to the traditional North- South model of development cooperation. While individual development cooperation programs differ in terms of size, geographic orientation, and modalities, emerging donors all underline that their form of development cooperation is distinct from the traditional, asymmetric donor-recipient model and that their aid approach is likely to be more effective because of the cultural proximity and similitude in socio-economic development trajectories with the developing countries.

Their lobbying for an acknowledgement of the key role played by SSDC has led to increasing recognition by the international community of SSDC as an effective model of development cooperation, which needs to be strengthened to increase the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Despite the existence of a restricted number of studies dealing with rising powers’ development aid policies, the literature lacks studies on the analytical and empirical comparative assessment of rising powers’ actorness in the field of SSDC. This paper’s comparative analysis of Turkey’s and selected G20 rising powers’ actorness in SSDC aims to fulfil the lacunae in the existing literature and to diversify the G20 relevant studies in the context of development, most specifically.

Given this, this study aims to explore how Turkey has been located among the G20’s rising donors who have been actively engaged in the South-South Development Cooperation (SSDC). In doing so, it aims to compare Turkey’s and the selected G20 rising donors’ bilateral, multilateral, geographical and sectoral aid distribution by using OECD ODA Data, UN ECOSOC’s Quadrennial Comprehensive Policy Review (QCPR), Aid data statistics and the relevant countries’ domestic development aid data. First, the study will try to explain the actorness of Turkey in the sphere of South-South Development Cooperation and question its role as a Southern donor. Second, it will compare the performance of Turkey’s rising donor status in terms of bilateral- multilateral, geographical and sectoral distribution of aid with that of other G20 rising donors. In the final analysis, it will present the weaknesses and the strengths of Turkey in the field of SSDC compared to its G20 peers.

⦁ ACTORNESS OF TURKEY IN THE SPHERE OF SOUTH-SOUTH DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION

⦁ Defining South-South Development Cooperation

There is no universally agreed understanding of the concept of South-South Cooperation (SSC). In the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), ‘‘Economic Development in Africa Report 2010: South-South Cooperation: Africa and the New Forms of Development Partnership’’, the authors define the concept of SSDC as ‘‘the processes, institutions and arrangements designed to promote political, economic and technical cooperation among developing countries in pursuit of common development goals’’1.

One of the main features of a south-south cooperation is that the recipient is generally a low-income country already benefiting from aid funds from other donors, and the aid provider is an emerging power which experienced a recent successful economic growth and development trajectory , aims to expand its international influence through widening ties with overseas countries, and is sometimes still receiving aid from other development partners2

Another key element of such cooperation is the idea of win-win partnership since South-south development providers reject the idea of the benevolent character of their development aid activities and rather put forwards the argument that their aid projects are based on mutual and win-win cooperation between the partners.

Another feature of SSDC is the important role played by the private sector partly because in south-south cooperation, “most aid is tied to goods and services provided by private firms” and “package deals consisting of aid, trade and investment flows are characteristic of such cooperation”3.

Furthermore, SSDC emphasizes the development and promotion of developing countries’ self-development and collective self-reliance capacity 4. They are opposed

1 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), ”Economic Development in Africa Report: South-South Cooperation: Africa and the New Forms of Development Partnership’‘. UNCTAD 2010.

2 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), ”Economic Development in Africa Report: South-South Cooperation: Africa and the New Forms of Development Partnership’‘. UNCTAD 2010.

3 Dreher Axel et al, “The European Union, Africa and New Donors Moving Towards New Partnerships. Highlights”. European Union, May 2015, final_highlights_11052015_en.pdf

4 Huang, Meibo, “South-South Cooperation, North-South Aid and the Prospect of International Aid Architecture’’, Vestnik Rudn International Relations No1,2015,p.26.

to any kind of interference in the domestic politics of the recipient countries as well as to any form of conditionality in their development cooperation activities.

Lastly, SSDC is based on a larger understanding of the concept of development cooperation, which should not only be restricted to aid funding but extended to other sources of finance such as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and trade that also contribute to tackle developing countries’ development issues.

Given these and others, which role has Turkey played so far in the field of SSDC as an aid provider?

⦁ On Turkey’s Actorness in the field of SSDC

Beforehand, it should be reminded that unlike other emerging donors, the case of Turkey is slightly different considering the hybrid nature of this country as a country in-between western and non-western culture.

On one hand, as a member of the OECD, Turkey adheres to the ODA definition provided by the OECD-DAC and therefore in principle the content of its development aid as well as the rules and modalities of providing aid to SSA fit into OECD-DAC pre-established rules and principles. Turkey also regularly reports its development assistance flows to DAC, which increases transparency in its official aid data and it regularly participates in the DAC committee meetings, although Turkey is not yet a member of the OECD-DAC. This proximity with western aid donors makes is likely to decrease its actorness as a SSDC provider with the likes of China for instance.

However, in the first half of the 2000s, the coming to power of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) accompanied with Turkey’s rapid economic boom has significantly changed the foreign policy landscape of Turkey. Turkey has become more assertive and pro-active in international politics and has shifted its foreign policy from a western-oriented and passive perspective to a pro-active non-western one. In this context, Turkey has hold membership in non-western platform such as MIKTA (Mexico, Indonesia, Republic of Korea, Turkey and Australia) and Turkey is also gradually building its own image as a global power in overseas regions. In the last decade, increasing willingness of Turkey to play an important role in international development cooperation has been largely acknowledged. For instance, in 2016, Turkey won the title of the “most generous” country in the field of development cooperation when considering its ratio ODA disbursement/GDP. Turkey has also geographically expanded its aid disbursement to far-away regions in Africa and Latin America.

Like south-south development aid providers, Turkey also increasingly considers its aid activities in SSA as a project based on the solidarity with and fraternity to the

African continent, which has been victim of years of colonial exploitation. Turkish officials underscore that ‘SSC forms an important aspect of Turkish development cooperation’5. The principle of solidarity, one of the defining elements of the southern model of development cooperation, is visible in Turkey’s engagement in Somalia 6. Likewise, Turkey’s development cooperation towards SSA is also based on the premise that African people should find their own solutions to development challenges, known as the principle of ‘African solutions for African problems’7.

Turkish leaders also use the principles of equality and win-win partnership in their development aid discourses towards SSA. Turkish leaders in their development assistance discourses in SSA seek to avoid ‘new-imperialism’ accusations while proposing a ‘mutual-benefit’ discourse, which means that their development aid perspective contains idealistic and pragmatic aspects.

In this context, Turkey’s president Erdogan once said that “Turkey has never been a colonial power in Africa, and now we come here as equals who ask for cooperation, not as a colonial power that is coming to exploit your resources”8. Turkey also praises its development path as a successful example that might inspire the African countries it sees as its fellow’s brothers. From an aid-recipient country to a potential aid donor in the world, Turkey is generally presented as a country with ‘‘much success and experience to share with LDCs’’9.

Turkey’s development cooperation activities also ‘’share commonalities with SSC (South-South Cooperation) donors, such as its increasing preference to deliver aid through bilateral rather than multilateral channels, its rejection of aid conditionality, its emphasis on national ownership, and its relative inexperience in strategic analysis and co-ordination.’’10 .

One of the specificities of Turkey in its development aid approach that distinguishes Turkey from both traditional and non-western emerging aid donor is its reliance on humanitarian diplomacy as the cornerstone of its development aid policy towards SSA. Humanitarian diplomacy, from the understanding of Turkish foreign policy

5 Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. ”Turkey’s development cooperation”,

6 Nganje Fritze, ‘’Two-way socialization between traditional and emerging donors critical for effective development cooperation’’, Africa up Close ,6 January 2014.

7 Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. ”Turkey’s development cooperation”,

8 Al Jazeera, ‘‘Erdoğan: Türkiye’nin Afrika’da sömürgeci geçmişi olmadı”, June 1, 2016,

9 Korkut, Umut and Civelekoglu, Ilke, “Becoming a Regional Power while pursing Material Gains: The Case of Turkish Interest in Africa’’, International Journal, Vol.68, no1, Winter 2012, p.194.

10 Sucuoglu, Gizem and Jason Stearns, “Turkey in Somalia: Shifting Paradigms of Aid”. South African Institute of International Affairs, Research report, No 24, November 2016, p.10-14.

makers is based on moral values and encompasses three dimensions, mainly – citizens of Turkey, policies toward crisis zones and global world order11. According to former Prime Minister Davutoglu, ‘‘Turkey has become deeply concerned with all forms of human inequality that exist in the world, especially those forms that impacts upon the dignity of the individual and the community’’12. The country’s most remarkable humanitarian feat has been its humanitarian engagement in Somalia at the height of the hunger crisis in 201113.

⦁ PERFORMANCE OF TURKEY AND G20 RISING POWERS IN SSDC: STATISTICAL OVERVIEW

⦁ Bilateral and Multilateral development aid

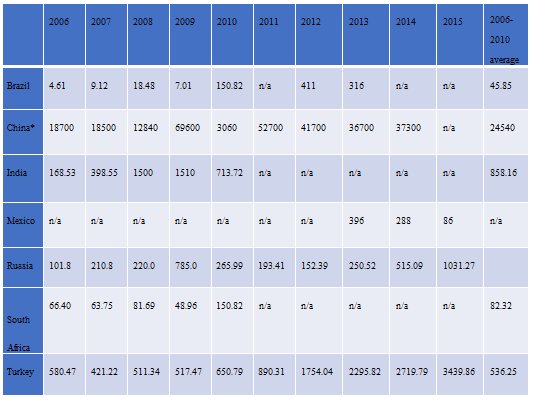

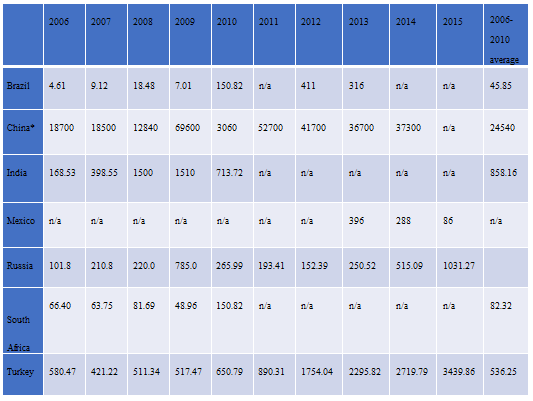

An analysis of the Table 1 below showcases that in average between 2006 and 2010, China ranks as the top provider of SSDC followed respectively by India, Turkey, South Africa and Brazil in terms of bilateral aid. The table further shows that Brazilian disbursement of development assistance tremendously increased in 2010 from 7.01 million USD in 2009 to 150.82 million USD in 2010 and that Chinese development aid significantly increased in 2009 and then sharply decreased in 2010. There has been a significant increase in India’s development aid in 2008 and 2009, which dramatically decreased in 2010.

Russia’s aid disbursement experienced a sharp decline in 2010 and an exponential increase in 2014 and 2015. Except for the years 2007 and 2009, South Africa’s aid provision kept increasing and the amount of its development aid almost tripled in the specific year of 2010. Since 2007 Turkey’s development aid provision has continuously increased and in 2012 there was a twofold increase in the amount compared to 2011. The reasons behind this tremendous increase of Turkey’s aid in 2012 lay in the fact that Turkey distributed 1.6 billion USD to the Syrian refugees and granted a loan of 1 billion USD to Egypt which was disbursed in equal parts in 2012 and 2013.

11 Davutoğlu, Ahmet, “Turkey’s Humanitarian Diplomacy: Objectives, Challenges and Prospects”,

Nationalities Papers: The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity, Vol 41, no: 6,2013,p. 865-870.

12 Davutoğlu, Ahmet, “A New Vision for Least Developed Countries’’, Center for Strategic Research SAM Papers, Vision Papers,No4, July 2012,p.3

13 Dal, Parlar Emel, Samiratou Dipama & Ferit Belder, “Assessing Turkey’s Development Aid Policy towards Africa: a constructivist perspective’’, International Relations and Dialogue of Cultures No 3,2014, p.104-124.

Table 1: Estimates of Development Cooperation Flows (USD millions)

Source: OECD-DAC, AidData dashboard

*China’s data are about aid commitment and not aid disbursement

Regarding multilateral development aid data, it stems from the Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA)’s 2016 report that in 2015 Turkey’s multilateral ODA was less than 2% of Turkish total ODA and that in 2016, bilateral ODA accounted for 6.327billion USD against 250.2 million USD for multilateral ODA14. The OECD specifically shows that Turkey’s contribution to multilateral institutions in 2016 went primarily to regional development agencies (68%), and then

14 Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA), TIKA Development Assistance Report 2016.

to respectively UN institutions (21%), and the World Bank group (2%) (OCED Statistics).

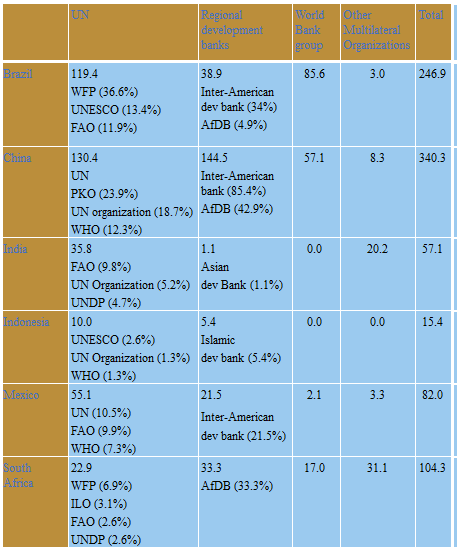

Like the case of Turkey, it is also estimated that China uses bilateral channels in most of its development cooperation. (93% in 2013) (OECD 2015) and that half of Chinese multilateral flows is provided by the Inter-American Development Bank, the World Bank Group and the African Development Bank (see Table 2 below). In the same line, India also distributes 90% of its development aid via bilateral channels15. However, most of its multilateral aid is disbursed through the UN system (see Table 2 below).

In contrast to Turkey, India and China, Indonesia mostly uses multilateral channels, most specifically the UN channels. However, it must be reminded that as seen in the table 2 between 2011 and 2013 the biggest multilateral recipient of Indonesia’s multilateral funds is the Islamic Development Bank 16. The same trend can also be seen between 2005-2009 in the case of South Africa whose bilateral development cooperation is only about 10% of its total aid 17. As seen in the table 2 the African Development Bank and the African Union are the biggest multilateral recipients of its multilateral aid. Brazil also seems to prioritize multilateral development aid because the OECD data indicates that in 2013, Brazil’s multilateral ODA accounted for 66% (208 million USD) of total ODA and that in 2015 Brazil provided 96 million USD of multilateral ODA, of which 57% disbursed to the UN and 43% to the Inter-American development bank18. Brazil and Mexico come closer in this respect because in 2014 Mexico’s multilateral ODA also accounted for 63% of its total ODA19.

Russia seems to lay in the middle among our selected case studies because in 2015 Russia’s multilateral ODA was about 22% of its total ODA and the biggest share of its multilateral ODA belongs to the World Bank Group (about 53% of its multilateral ODA in 2015).In the same year it attributed 36% of its multilateral ODA to the United Nations and 1% to regional development banks and other multilateral organisations20.

15 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Development Co-operation by Countries Beyond the DAC: Towards a more complete picture of international development finance, OECD, May 2015.

16 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Development Co-operation by Countries Beyond the DAC: Towards a more complete picture of international development finance, OECD, May 2015.

17 Yanacopulos H, ‘The Janus Faces of a Middle Power: South Africa’s Emergence in International Development’, Journal of Southern African Studies 40, No1,2013,p.203–216.

18 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Development Co-operation Report 2017: Data for Development, Paris: OECD Publishing 2017.

19 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Development Co-operation Report 2017: Data for Development, Paris: OECD Publishing 2017.

20 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “The Russian Federation’s Official Development Assistance (ODA)”, assistance.htm

Table 2: Estimates of funds accorded to the multilateral system: Non-OECD providers of Development Cooperation beyond the DAC (2011-2013 three-year average, USD million, current prices

Source: OECD, Development Cooperation by Non-OECD Countries Beyond the DAC Towards a more complete picture of international development finance , OECD May 2015, operation%20by%20Countries%20beyond%20the%20DAC.pdf

The comparative assessment of Turkey and the other selected G20 rising powers’ development aid shows that whereas Turkey, China and India and Russia distribute most of their aid bilaterally, Brazil, South Africa, Indonesia and Mexico prefer using multilateral channels. Russia appears to adopt a middle-ground approach since although its bilateral ODA share seems to be bigger, the share of its multilateral ODA is relatively higher than the ones of Turkey, India and China. Apart from Turkey, China and South Africa, which prioritise regional development bank groups, the UN system still remains the main recipient of the multilateral aid from Brazil, India, Mexico and Indonesia. In addition to this, it must be underlined that as seen in Table 2 the UN’s specialised agencies on food security and agriculture are the main channels of funding used by the above-mentioned G20 rising powers choosing to contribute most of their aid through UN channels. Russia turns out to be particular in this context because the majority of its multilateral ODA goes primarily to the World Bank Group.

The table 3 below further ranks Turkey and the selected G20 rising powers in terms of their core and non-core multilateral contributions to the UN development system (UNDS). Core contributions are resources attributed to UN entities without restrictions, while non-core contributions are resources distributed to UN entities with some restrictions with regards to their use and application. In other words, with non- core multilateral contributions, states retain a margin of control with respect to the way the funding is spent. The table 3 below indicates that in terms of average contributions to the UN core development related activities, Turkey ranks as the 5th top contributor after Mexico, Brazil, Russia and China. Unlike China, Indonesia and Russia, Turkey with the likes of Brazil, Argentina, India, Mexico and South Africa provided more non-core contributions than core between 2014 and 2016.

Table 3: G20 Rising Powers’ 2014-2016 average contribution for UN- Development related operational activities in thousands US dollars

Core

Non-Core

Argentina

10,192,666.7

155,575,000

Brazil

29,856,333.3

258,658,667

China

63,379,666.7

55,797,000

India

15,916,666.7

27,202,666.7

Indonesia

9,661,333.33

8,307,333.33

Mexico

26,852,000

57,480,333.3

Russia

44,414,333.3

42,759,666.7

South Africa

6,779,333.33

7,355,333.33

Turkey

24,075,333.3

37,750,000

Source: Self-calculated data based on the UN ECOSOC’s Quadrennial Comprehensive Policy Review (QCPR).

⦁ Sectoral and Geographical Distributions of Development aid

Regarding the sectoral distribution of development aid, TIKA’s 2016 report shows that Turkey spent respectively 780 million USD for the “Social Infrastructure and Services Sector”, 90 million USD for the “Economic Infrastructure and Services Sector”, 23 million USD for the “Manufacturing Sector” and lastly 4 million USD for “Multi-Sectoral activities”21.

In the case of Brazil, the AidData dashboard indicates that between 2000 and 2014, the top sectoral priorities of Brazil’s aid are respectively “Education” (36.11 million USD), “Agriculture” (19.59 million USD) and “Health” (17.65 million USD)22.

In the case of China, between 2000 and 2014, the main sectors where China invest its financial aid are respectively “Energy Generation and Supply” (134.1 billion USD), “Transport and Storage” (88.8 billion USD) and “Industry, Mining and Construction” (30.3 billion USD)23.

The 2014 White Paper on China’s Foreign Aid mentions that between 2010 and 2012, the main sectors of Chinese development aid (more than half went to Africa) were “economic infrastructure” (45% of bilateral funds) and “social and public infrastructure” (28% of bilateral funds)24.

In the case of India, between 2006 and 2014, “Energy generation and supply” (882.72 Million USD) followed by “Transport and Industry” (550.19 million USD) rank among the top first sectoral priorities of India in its development aid program25.

According to the OECD data, Russian Federation’s bilateral development cooperation mostly concentrated on the following sectors: public finance, nutrition, health, education and food security. While distributing its bilateral development aid, Russia prioritizes technical assistance projects, capacity building and scholarships, budget support and debt relief26.

21 Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA), TIKA Development Assistance Report 2016.

22 AidData dashboard,

23 AidData dashboard,

24 Information Office of the State Council (2014) (the 2014 White Paper)

25 AidData dashboard,

26 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “The Russian Federation’s Official Development Assistance (ODA)”, assistance.htm

The main sectors of South Africa’s development aid between 2000 and 2014 are respectively “Government and Civil Society” (89.23 million USD), “Agriculture” (61.53 million USD) and “Education” (37.18 million USD)27.

In sum, this paper argues that in terms of sectoral priorities, like China and India, Turkey seems to focus more on economic and social infrastructures and to pursue in this context a win-win partnership. This means that Turkey follows one of the core principles of SSDC which is about using aid to consolidate economic relations between the two partners in the SSDC. In contrast to Turkey, China, and India, the other G20 rising powers, namely Brazil, Russia and South Africa seem to give priority to social sectors such as health and education and agriculture.

Coming to the geographical distribution, TIKA’s 2016 report shows that the top recipients of Turkish bilateral official development assistance in 2016 were respectively Syria, Somalia, Palestine, Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kyrgyzstan, Macedonia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and Niger. Out of these 10 countries, 3 are located in the Middle East (Syria, Palestine and Afghanistan), 3 are in South- East Europe (Macedonia, Azerbaijan and Bosnia and Herzegovina), two are in Central Asia (Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan), 1 from West Africa (Niger) and 1 from East Africa (Somalia)28.

In the case of Brazil, an examination of the AidData dashboard showcases that between 20004 and 2014, Brazil ‘s main aid recipients include two west African countries ( Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde) , one north African country (Algeria) , 2 south African countries( Angola and Mozambique), one central African country ( Sao Tome and Principe), one Caribbean country ( Haiti), one South-east Asian country (Timor-Leste), and one south American country ( Paraguay)29. Here it must be noted that with the exception of Algeria and Haiti, all of the remaining top nine recipients of Brazil’s aid are, like Brazil, officially Lusophone. This distribution clearly shows that in development cooperation Brazil aims to strengthen its status as a regional power in a specific ‘region’ of the global South30.

In terms of ODA, between 2004 and 2014, China’s top recipients include: 1 Caribbean country (Cuba), 3 West African countries ( Cote d’Ivoire, Nigeria and Ghana), 2 east African countries(Ethiopia and Tanzania), 1 central African country

27 AidData dashboard,

28 Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA), TIKA Development Assistance Report 2016.

29 AidData dashboard,

30 Cabral L, R Giuliano & J Weinstock, ‘Brazil and the Shifting Consensus on Development Co- operation: Salutary Diversions from the ‘Aid-effectiveness’ Trail?’, Development Policy Review, 32, no 2,2014, p.179–202.

(Cameroun), 1 south Africa country (Zimbabwe),1 South-East Asian country (Cambodia) and 1 South-Asian country (Sri Lanka)31.

Between 2006 and 2014, the top recipients of India’s aid include: 2 west African countries (Nigeria and Mali), one east African country (Ethiopia), one south African country (Mozambique), two Middle Eastern countries (Syria and Afghanistan), 3 South Asian countries (Bhutan, Nepal and Sri Lanka) and one South-East Asian country (Myanmar)32.

In 2011, Eastern Europe and central Asia and SSA equally benefited each from 28% of Russian total ODA distribution while Latin America and Caribbean benefited each from 20% of Russian ODA. The same distribution is respectively 12% for South Asia, 9% for East Asia and 3% for Pacific and for the MENA region33.

With the exception of Timor-Leste (a south-east Asian country) and Haiti (Caribbean country), South Africa concentrates the most of its development assistance on the SSA continent (Guinea Bissau, Guinea, Cape Verde, DRC, Sao tome and Principe, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Lesotho)34. This is mainly due to the fact that South Africa prioritises Africa in its SSDC policies35.

All these comparative geographical distributions of the selected G20 rising powers’ bilateral development aid show that whereas Turkey, Brazil and South Africa concentrate their SSDC activities on specific regions with strong historical and/or linguistic ties, China, India and Russia reach more geographically and culturally diversified groups in their SSDC projects.

⦁ ASSESSING TURKEY ‘S PERFORMANCE IN THE FIELD OF SSDC COMPARED TO ITS G20 PEERS

This study argues that in recent years the importance of SSDC as an alternative model of development cooperation to the traditional north-south model has been increasingly acknowledged by both traditional and rising powers. The adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development by the UN General Assembly in September 2015 has further strengthened the importance of SSDC in the field of international development cooperation and one of the key models through which the delivery of the UN

31 AidData dashboard,

32 AidData dashboard,

33 Ministry of Finance, “The Russian Federation ODA: National Report”, 2012,Available at:

34 AidData dashboard,

35 Dirco, “White Paper on South African Foreign Policy – Building a Better World: The Diplomacy of Ubuntu”, Pretoria: South Africa: Department of International Relations and Cooperation,2011.

Sustainable Development Goals can be improved. This means that SSDC has already been benefiting from recognition by the international community, including Western donors. This explains why rising powers are actively engaged in SSDC.

This study has shown that Turkey, China and India give more preference to economic and social infrastructures and in this regard pursue a win-win partnership, one of the core principles of SSDC. Compared to Brazil, Russia and South Africa which seem to give priority to social sectors such as health and education and agriculture, Turkey appears to be a stronger SSDC actor with the like of China and India.

Like the cases of China and India, Turkey distributes most of their aid bilaterally. About 98% of Turkey’ s development aid is bilateral. The preference given to bilateral over multilateral development aid by Turkey, China and India lays in the fact that these countries seek to show their distinctiveness in the field of SSDC through following their own rules, principles and modalities in the formulation and disbursement of their aid activities. In this sense, like China and India, Turkey by prioritizing bilateral aid expressed its willingness to follow its own model of development cooperation, which as seen above presents strong similarities with SSDC. Bilateral development cooperation is likely to increase Turkey’s actorness in the field of SSDC as Turkey would have free-hand as to where and how to spend its money.

However, an extensive focus on bilateral development aid might have reverse negative impact on Turkey’s and the other G20 rising powers’ quest for actorness in the field of SSDC because If Turkey’s bilateral aid rules and modalities significantly contrast with the established rules of multilateral development aid, it is likely that international donors( especially western donors) might be reluctant to grant recognition of Turkey’s actorness-seeking policies in the field of SSDC and Turkey’s actions in the field of SSDC might be seen as illegitimate by the international community. This is why non-core multilateral development aid play a key role in terms of allowing rising powers willing to show their particularities in the field of SSDC to reach this objective without being taxed as “outsiders” of the current international order. An analysis of the above data has shown that with the likes of Brazil, Argentina, India, Mexico and South Africa, Turkey seems to prefer non-core multilateral contributions compared to the core ones. This is an indication of Turkey’s willingness to retain control over the modalities of the use of their financial contribution by multilateral institutions while remaining part of this multilateral development aid order. In this regard, this paper argue that Turkey should prioritize non-core multilateral development aid over bilateral one as the main channel through which Turkey can show its distinctiveness in the field of SSDC while remaining attached to the multilateral rules of development aid.

Similar to China and South Africa, Turkey prioritizes more regional development bank groups than UN Agencies for the channel of SSDC. More than half of Turkey’s

multilateral funding is provided through channels outside of the UN. An integrated overview of Turkey’s financing strategies towards UN and non-UN funds suggests that although Turkey’s financial contribution has been increasing, it should redress the imbalance by contributing more to the funds, agencies and programmes of the UN.

Geographical, cultural and historical connection is another element of SSDC. Like Brazilian and South African cases, Turkish aid concentrate on specific regions with strong historical and/or linguistics ties. In this sense, Turkey’s development path and experience is likely to be followed in an efficient manner by the recipient countries given that they share closer historical and linguistic ties. Turkish case differs from Chinese, Indian and Russia’s whose geographical reaches appear to be almost all encompassing, as the recipient countries are very diversified.

CONCLUSION

This article examined Turkey’s actorness in the field of SSDC in comparison with eight other G20 rising powers. The comparative task focused on a two -layered framework, namely bilateral vs multilateral aid and the geographical and sectoral distribution of development aid of the selected G20 rising powers.

Regarding our selected case studies, the comparative data used in this study have shown that whereas Turkey, China and India provide most of their flows bilaterally, Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa, and Mexico channel a large share of their overall funding through multilateral organisations. This article argues that compared to Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa and Mexico, which prioritise multilateral channels over bilateral ones, China, India and Turkey give more preferences to bilateral development aid. Although bilateral channels provide donor countries with more flexibility opportunities over the rules and modalities of aid formulation and disbursement, it can negatively impact of the legitimacy of these countries’ aid projects vis-à-vis the international community of donors and ordinary citizens, especially when bilateral aid rules challenge the existing multilateral development aid norms. This leads to the point that Turkey is likely to consolidate its actorness in the sphere of SSDC through non-core multilateral aid because it would have the opportunity to show up its particularities as a SSDC actor while increasing international support and legitimacy of its aid activities. Non-core multilateral aid allows Turkey to retain some control over the use of the money given to multilateral institutions while remaining attached to the multilateral rules and as such would have more positive impact on Turkey’s actorness in the field of SSDC.

Furthermore, the data on geographical distribution have shown that compared to, China, Russia and India, Turkey is less e eager to pursue a geographically and culturally extended actorness policies through bilateral SSDC because its top aid recipients are mostly concentrated on countries with strong historical and cultural ties with Turkey.

In summary, Turkey and the selected G20 rising powers are more capable to achieve and consolidate their actorness in the field of SSDC through prioritizing non-core multilateral development aid because it provides rising powers with greater marge of maneuverer in terms of following the core principles of SSDC in the formulation and implementation of their development aid policies while widening international support of their actions.

REFERENCES

AidData dashboard,

Al Jazeera, ‘‘Erdoğan: Türkiye’nin Afrika’da sömürgeci geçmişi olmadı”, June 1, 2016, gecmisi-olmadi

Cabral L, R Giuliano & J Weinstock, ‘Brazil and the Shifting Consensus on Development Co-operation: Salutary Diversions from the ‘Aid-effectiveness’ Trail?’, Development Policy Review, 32,no 2,2014:179–202.

Davutoğlu, Ahmet, “Turkey’s Humanitarian Diplomacy: Objectives, Challenges and Prospects”, Nationalities Papers: The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity, Vol 41, no: 6,2013: 865-870.

Davutoğlu, Ahmet, “A New Vision for Least Developed Countries’’, Center for Strategic Research SAM Papers, Vision Papers,No4, July 2012 .

Dal, Parlar Emel, Samiratou Dipama & Ferit Belder, “Assessing Turkey’s Development Aid Policy towards Africa: a constructivist perspective’’, International Relations and Dialogue of Cultures No 3,2014 :104-124.

Dirco, “White Paper on South African Foreign Policy – Building a Better World: The Diplomacy of Ubuntu”, Pretoria: South Africa: Department of International Relations and Cooperation,2011.

Dreher Axel et al, “The European Union, Africa and New Donors Moving Towards New Partnerships. Highlights”. European Union(May 2015), final_highlights_11052015_en.pdf

Huang, Meibo, “South-South Cooperation, North-South Aid and the Prospect of International Aid Architecture’’, Vestnik Rudn International Relations No1,2015:24- 31.

Information Office of the State Council (2014) (the 2014 White Paper)

Korkut, Umut and Civelekoglu, Ilke, “Becoming a Regional Power while pursing Material Gains: The Case of Turkish Interest in Africa’’, International Journal, Vol.68, no1(Winter 2012):187-203.

Ministry of Finance, “The Russian Federation ODA: National Report”, Available at:

Nganje Fritze, ”Two-way socialization between traditional and emerging donors critical for effective development cooperation’’, Africa up Close ,6 January 2014, accessed on 28 October 2017, at, socialization-between-traditional-and-emerging-donors-criticalfor-effective- development-cooperation/,

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Statistics at https://stats.oecd.org/

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Development Co-operation by Countries Beyond the DAC: Towards a more complete picture of international development finance, OECD, May 2015.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Development

Co-operation Report 2017: Data for Development, Paris: OECD Publishing 2017.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “The Russian Federation’s Official Development Assistance (ODA)”,

Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. ”Turkey’s development cooperation”,

Sucuoglu, Gizem and Jason Stearns, “Turkey in Somalia: Shifting Paradigms of Aid”. South African Institute of International Affairs, Research report, No 24, (November 2016).

Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA), TIKA Development Assistance Report 2016.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), ”Economic Development in Africa Report: South-South Cooperation: Africa and the New Forms of Development Partnership’‘. UNCTAD 2010.

Yanacopulos H, ‘The Janus Faces of a Middle Power: South Africa’s Emergence in International Development’, Journal of Southern African Studies 40, No1,2013:203– 216.