by Michael Rubin

Michael Rubin, editor of the Middle East Quarterly, is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and senior lecturer at the Naval Postgraduate School. (detailed CV is attached to end)

Last month, Turkish prosecutors issued a 2,455-page indictment detailing an alleged plot to overthrow Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan by an elaborate network of retired military officers, journalists, academics, businessmen, and other secular opponents of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). Although the precise facts of the case are not yet clear, the so-called Ergenekon conspiracy appears to be a largely fictionalized construct, with an ongoing investigation geared mainly to warding off constitutional challenges to the ruling party, not coups.

Background

The AKP, the latest of several Turkish Islamist political reincarnations, rose to power in November 2002 on a wave of popular dissatisfaction with economic malaise and corruption scandals within establishment parties. Although the AKP captured barely a third of the vote, this translated into a two-thirds parliamentary majority because much of the popular vote went to parties that failed to meet the 10% electoral threshold for winning seats.

When the AKP came to power, Erdogan disavowed any intention to implement the Islamist agenda he had embraced in the past. Nevertheless, his government worked to weaken or disable all of the inherent checks that would prevent the establishment of an Islamic state in the longer run.

Although Erdogan has presided over economic growth averaging nearly 7% per year, his management of the economy has been deeply politicized. Turkey’s banking and financial board now consists exclusively of AKP appointees, most of whom had careers in Islamic finance institutions. A number of civil servants in technocratic posts have said that the AKP has instituted an interview process, controlled by party loyalists, to supplement the examination process that screens government employees.

The AKP has greatly compromised the independence of the media. Its most notorious encroachment came last year, when the government seized control of the country’s second largest media group, ATV-Sabah, sold it to a holding company managed by Erdogan’s son-in-law, and pressed state banks and the emir of Qatar to provide the financing.[1] In addition to cultivating a massive loyalist media base, the prime minister has effectively bought the silence of other large media conglomerates by distributing lucrative government contracts and privatization deals.

The AKP has also limited the military’s influence in politics by reducing the power of the National Security Council and placing it under a civilian head. This is not a cosmetic change. Almost every month, government ministers appear before the council to answer questions and justify government actions. The cabinet prioritizes the National Security Council’s recommendations. Civilian leadership has removed the military’s ability to set the agenda and, in practice, strengthened the separation between uniformed services and civilian governance.

The Erdogan government has tried to undermine Turkey’s secular educational tradition, most notably by lifting a long-standing ban on religious attire in universities. According to Egitim-Sen, a left-of-center teachers’ union, Islamic influences are creeping into textbooks.[2] Only fierce public opposition stalled more sweeping educational initiatives.

President Ahmet Necdet Sezer served as a critical check on the AKP’s ambitions. During his presidency, he vetoed 65 bills, largely on constitutional grounds, negating more than 6% of those submitted by the AKP-dominated parliament.[3] For example, he vetoed a bill that would have lowered the mandatory retirement age of judges. Had it passed, the bill would have greatly expedited Erdogan’s drive to replace Turkey’s justices with party loyalists. Since the AKP gained control of the presidency last year, this check has been eliminated.

This leaves the judiciary as most powerful check on the AKP’s power. The Constitutional Court, which has sweeping authority both to overturn legislation and ban political parties that contravene Turkey’s secular constitution, has remained staunchly independent thus far because the president appoints the justices (from among candidates nominated by other judicial organs). Although AKP co-founder and parliamentary speaker Bulent Arinc warned in 2005 that the Constitutional Court could be dissolved if it continued to veto legislation,[4] it remains intact and resolute. However, the election of AKP loyalist Abdullah Gul as president means that its independence won’t last forever.

The AKP has had more success exerting influence over the lower courts. In December 2007, the government enacted a new law that requires all judicial candidates to take an oral exam administered by the AKP-controlled Ministry of Justice (codifying a practice already in place). The Union of Turkish Bar Associations organized a demonstration by thousands of lawyers, arguing that this law would allow the ministry to screen candidates based on their political and religious views. According to the US State Department’s annual report on human rights practices in Turkey, the Erdogan government has “launched formal investigations against judges who had spoken critically of the government.”[5]

Wherever the AKP has managed to penetrate the judiciary, the results have been worrisome. Pro-AKP judges have placed liens against the property of political opponents, seized media outlets, and overturned earlier decisions levied against Islamists.

The AKP has extensive control over the police. Followers of Fethullah Gulen, a cult leader whose followers seek to Islamize Turkish society if not overthrow the secular order have, according to a broad range of Turkish journalists, civil society leaders, and even Gulen followers, infiltrated the police. The police often target secular opponents of the AKP on both the national and local level. Businessmen who donate money to AKP opponents have complained of police harassment and spurious investigations.

The AKP has also expanded the authority of the police. In February 2007, according to the State Department, parliament “significantly expand[ed] the authority of security forces to search and detain a suspect.”[6] Four months later, the Turkish news newspaper Radikal noted a rise in allegations of mistreatment and torture by police in Istanbul.[7]

One of the most egregious abuses of power in the criminal justice system involved Yucel Askin, rector of Yuzuncu Yil University in Van. Askin had staunchly opposed Erdogan’s efforts to reduce barriers to college admission for students educated in exclusively religious seminaries and also had enforced the ban on Islamic headscarves on campus. In 2005, police raided his house in search of illicit artifacts (Askin was a known collector of antiquities) and hauled him off to jail. However, they were forced to release him after it was discovered that he had government licenses for every artifact in his possession. Three months later, police arrested him again, this time on charges of accepting kickbacks from the university’s purchase of medical equipment. Again, however, he was released when a judge determined that the university bought the medical equipment in question a year before Askin became rector. While Askin got his life back, the university’s general secretary was not as lucky. Enver Arpali committed suicide after being held for months in prison without trial in the same case.[8]

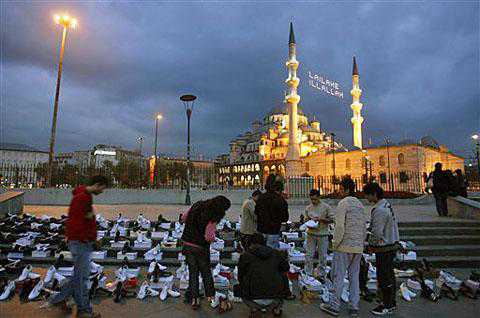

While the AKP has moderated its Islamist agenda at the national level in order to maximize its appeal at the ballot box and stave off the threat of military or judicial intervention, secular opposition leaders fear that this moderation is tactical – that Erdogan is biding his time until obstacles are out of the way. “Democracy is like a streetcar. When you come to your stop, you get off,” he said when he was mayor of Istanbul in the 1990s.[9] At the local level, where tactical caution is not required, the AKP continues to pursue a more radical agenda in municipalities firmly under its control, such as banning alcohol and imposing gender segregation in public transport.

Secular leaders also point to the prime minister’s dictatorial style as a harbinger of what lies ahead. Erdogan, who once bragged of being “the imam of Istanbul” when he was mayor of the city,[10] rules over the AKP in much the same fashion. “Erdogan accepts no advice and no criticism. He’s become a tyrant,” one member of the AKP’s own parliamentary bloc told The Economist.[11] AKP members say that Erdogan handpicked the slate of parliamentarians who could run for re-election under his banner. While the dictatorial control of Turkish political parties is a phenomenon that spans the political spectrum – affecting the center-left Republican Peoples Party (CHP) and National People’s Party (MHP) just as much – the problem is more worrisome in a ruling party that governs without coalition partners.

Rather than bridge the gap between Turkey’s religious and secular constituents, Erdogan has widened it. Although the AKP won 47% of the popular vote in the latest parliamentary elections last year, millions of Turks took part in the waves of anti-government demonstrations that erupted the preceding May.[12] In one recent public opinion poll, only 30% of respondents said they would vote for the AKP if elections were held today.[13]

Staunch secularists believe that this is an insufficient mandate to make sweeping unilateral decisions on basic national issues, and they are using one of their last remaining institutional footholds – the Constitutional Court – to do something about it. In recent months, the court has overturned Erdogan’s attempt to allow Islamic headscarves in universities and formally sanctioned the AKP for its contravention of the constitution (as well as levying financial penalties against it). Erdogan’s supporters denounce such opposition as anti-democratic and reactionary, even fascist. It is in this context that the Ergenekon investigation emerged.

The Investigation

Allegations of a vast conspiracy by prominent secularists to murder and terrorize civilians first began to dominate the headlines in March 2007, when the left-of-center Turkish political weekly Nokta published what it claimed to be diary entries of retired admiral Ozden Ornek. The excerpts discussed a 2004 plot to incite violence as a precursor to a military coup. Although Ornek denied the authenticity of these excerpts, their publication revived a long-standing claims that a shadowy network of generals, intelligence officials, and organized crime bosses have worked in tandem over the years to stage acts of violence.[14]

The timing of these explosive revelations raised suspicions, occurring just weeks before parliament was scheduled to elect a new president, amid widespread speculation that the AKP would attempt to put a dedicated Islamist in the post. While Gul (like Erdogan) has moderated his public pronouncements over time, he was once very direct. As Islamists rose in political power in the mid-1990s, Gul said, “This is the end of the republican period . . . the secular system has failed and we definitely want to change it.”[15]

As Erdogan’s attempts to anoint Gul to the presidency faltered for lack of a parliamentary quorum and the country prepared for early elections, pro-AKP media outlets produced a stream of stories about an alleged “deep state” conspiracy, reporting that went hand in hand with efforts by Erdogan and his allies to portray secularists as the true enemies of Turkey’s constitutional order.

In June 2007, police raided an apartment belonging to a retired military officer in the Umraniye district of Istanbul and discovered a cache of 27 hand grenades,[16] providing a modicum of evidence to support what heretofore had been only rumor and coincidence. According to police investigators, the grenades matched another one that was used (but failed to detonate) in a May 2006 attack on the office of the center-left newspaper Cumhuriyet.[17]

The government, for its part, argues that many of the Islamist terror attacks that have taken place in Turkey in recent years are false flag Ergenekon operations. In May 2006, an assailant swept into the Danistay, the supreme administrative court. Shouting “God is great” and “I am a soldier of God,” he sprayed the justices with gunfire, in alleged protest for the Court’s refusal to ease restrictions on the Islamist headscarf, murdering Mustafa Yucel Ozbilgin. Tens of thousands of Turks attended his funeral, chanting anti-AKP slogans, and heckling Gul (then foreign minister) when he arrived to represent the government.[18] According to police, the assailant confessed to participating in the Cumhuriyet grenade attacks, although his past Islamism and the lack of evidence showing any linkage leads many secularists to conclude that the killer gave a false confession to further glorify his exploits.

In a similar fashion, various pro-AKP media outlets have suggested that the murders of an Italian Catholic priest, Turkish Armenian writer Hrant Dink and the April 2007 murder of Christian missionaries were also Ergenekon corollaries.[19] The problem is that the Islamists captured in these cases have no credible links to the secular establishment.

The Umraniye raid led to the first of several arrest sweeps over the next thirteen months. All of them coincided very closely with major political developments and lacked adherence to basic investigatory and judicial protocols. Authorities detained nearly all suspects prior to issuing an indictment. While such detentions have occurred before in security cases, seldom if ever did they involve such senior personalities, continue for so long and with such sensationalist media leaks.

Most of the arrests occurred in middle-of-the-night raids. Police held these suspects incommunicado for the first 24 hours without allowing them even to call their lawyers. In most cases, police initiated questioning only on the fourth day of detention in order to raise detainee anxiety. Lawyers for those arrested say that police have refused to furnish them with transcripts of the interrogations.

Kuddusi Okkir was arrested in June 2007 on suspicion of financing the alleged Ergenekon plot and held for over a year without charge. For the first eight months he was held solitary confinement, with the authorities refusing even to allow his wife to visit. When he was diagnosed with lung cancer while in prison, officials rejected numerous petitions to enable him to receive outside medical treatment. They finally relented when he fell into a coma in early July 2008, but by then it was too late – he died four days later without ever regaining consciousness.[20] Another detainee held without charge, Ayse Asuman Ozdemir, developed liver disease while in captivity and was also denied critical medical treatment. She finally received furlough after the death of Okkir caused an embarrassing uproar for the government, but it may also be too late to save her.[21]

On March 21, Abdurrahman Yalcinkaya, chief prosecutor of Turkey’s Court of Appeals, filed a lawsuit in the Constitutional Court demanding the closure of the AKP and the banning of over 70 top AKP officials from politics for five years for “violating the principles of a democratic and secular republic.” Erdogan responded hours later with a midnight roundup of new Ergenekon suspects. Whereas previous suspects arrested had been largely fringe figures, this time the net was widened to include some of the most prominent secular intellectuals in Turkey, such as Dogu Perincek, leader of the Workers’ Party; the bed-ridden octogenarian editor of Cumhuriyet, Ilhan Selcuk; and Kemal Alemdaroglu, a former president of Istanbul University. It appears that Erdogan also put the offending judges under surveillance. A scandal erupted in May when the vice-president of the Constitutional Court complained that he was being followed. Uniformed police responding to his complaint found that his pursuers were undercover officers.[22] However, there have been neither subsequent charges nor explanations of the incident.

On July 1, as Yalcinkaya stood before the Constitutional Court to present his case for closing the AKP, Turkish police responded with another tit-for-tat roundup of leading secularists, including Mustafa Balbay, the Cumhuriyet Ankara bureau chief; Sinan Aygun, the president of the Ankara Chamber of Commerce; retired general Sener Eruygur, the president of the Ataturk Thought Society, and retired general Hursit Tolon. Once again, the timing of the raid was not coincidental – the police received their warrant on June 29, but delayed executing it until Yalcinkaya’s arguments were underway.[23]

On July 24, police detained another 26 people, including several members of the Workers’ Party and staff members of Milli Cozum, a right-wing journal, who were charged with “insulting top state officials via media organs.”[24] In total, over one hundred journalists, politicians, and others have been detained in the investigation.[25]

Many of the suspects in these later waves of arrests appear to have been victims of expansive electronic surveillance and guilty of little more than criticism. Those who have been released from detention describe interrogations which resemble fishing expeditions, with police asking them questions such as “Are you aware that you have insulted government leaders many times?” and “Why do you swear so much when you talk on the phone?” Police have even asked some to list with whom they talked when they attended receptions at the US embassy.[26] Selcuk was confronted with wiretapped conversations he had with Cumhuriyet foreign correspondents, discussing their work and story ideas. Ufuk Buyukcelebi, editor of Tercuman, told reporters that police confronted him with a phone tap showing that he had said the AKP “would be closed.”[27] Balbay says that all police questions related to his critical reporting on the AKP.[28] G-9, a group of nine press associations, called the arrests “an effort to silence opposition journalists.”[29]

Another disturbing aspect of the investigation is the cozy relationship between investigators and pro-AKP media outlets. The most egregious example of this came in May 2008, when the Islamist daily Vakit published an apparently wiretapped conversation between the deputy leader of the CHP and a governor.[30]

When the authorities finally unveiled an indictment in July 2008, the contents were unconvincing. The prosecutors said they prepared the indictment with the assistance of 20 witnesses whose identities they refuse to reveal. According to CNN-Turk, these witnesses will also testify in secret.[31] The “coup diary” was omitted from the indictment,[32] even though its alleged contents were the primary impetus for the Ergenekon prosecution. Accordingly, the accused cannot address the authenticity of the diary as it will not be entered into evidence. The indictment appears to absolve both the military and the Turkish intelligence service,[33] and limits the charges to terrorism or forming an illegal group, rather than plotting a coup per say.

Especially troubling is that, despite being a couple thousand pages long, the indictment lacks specificity as to which suspects are charged with what crimes. Indeed, many of the charges center on incitement and interfering in government work, the type of language more common in dictatorships like Syria and Saudi Arabia than in Turkey. Selcuk, for example, is accused of “providing guidance, with his writings, to the suspects engaged in a coup effort,”[34] a charge that an Islamist newspaper has also leveled against this writer.[35]

Another concern is the fact that Zekeriya Oz, the lead prosecutor in the case, is a virtual unknown, in his early thirties, with previous experience only as a public prosecutor in two small towns. This has raised questions as to his competence and whether he has the stature to resist political interference.

Even the limited amount of physical evidence in the case is only as reliable as the integrity of the police who uncovered it. Suspiciously, the grenades seized in Umraniye were reportedly destroyed by court order (though some reports have suggested that only the explosive cores were destroyed).[36] Should the justices uphold the police reports, the defense will be unable to advance alternate theories about the provenance of the grenades, the availability of their type across Turkey, or the linkage between them and other incidents.

At any rate, there are widespread suspicions that police investigators may have planted evidence. On April 10, 2008, workers at the Ankara Chamber of Commerce reported the discovery of a handgun hidden in a toilet in Aygun’s private office, which Aygun had them promptly report. His subsequent arrest led his associates to suspect that the gun had been planted to be found during a subsequent raid. After his July 1 arrest, Nuri Gurgur, the organization’s assembly chair, commented, “If we had not found that handgun then, the police would surely find it today, and it would be impossible for us to prove that Aygun had nothing to do with the gun.”[37] Such suspicions will rise as the indictment focuses on secret witnesses and computer files whose origins are already disputed.

What Next?

Throughout this saga, pundits close to the ruling party have repeatedly drawn equivalence between the Constitutional Court case and the Ergenekon investigation. “Circles who invited everyone to have respect for the judicial process in the [AKP] closure case raised hell the other day during the Ergenekon arrests and made accusations that Turkey has become a ‘police state,’” columnist Cengiz Candar wrote, “But these same groups regarded the closure case as the judiciary’s business.”[38] Ali Aslan, a columnist for the Islamist daily Zaman, expressed similar logic.[39] The obvious subtext of such columns, many of which reference private conversations with the prime minister, is that those who defend Turkey’s secular tradition have no right to demand rule of law and or complain about prosecutorial misconduct. They also indicate that the ruling party may be more interested in headlines than in actually seeing the Ergenekon prosecution through.

In the end, the Constitutional Court did not ban the prime minister from office or strip his parliamentary immunity, making it more difficult to determine to what extent the Ergenekon case is fabrication or exaggeration. An Istanbul court slated to hear the Ergenekon case has cleared its docket until April 2009. At stake when a verdict is returned on Ergenekon, though, will not just be Turkish national security, but also the credibility of the judiciary.

Notes

[1] “Circulation wars; Turkish media,” The Economist, 10 May 2008.

[2] “Flags, veils and sharia: Turkey’s future,” The Economist, 19 July 2008.

[3] Sabah (Istanbul), 30 March 2007.

[4] Cited by columnist Sahin Alpay, Zaman, 7 May 2005. Review of the Turkish Islamist press, BBC Monitoring, 7 May 2005.

[5] US State Department, Country Report on Human Rights Practices, 2007.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid; Radikal, 22 June 2007.

[8] Sabah, 13 November 2005.

[9] “The Erdogan Experiment,” The New York Times, 11 May 2003.

[10] Hurriyet, 8 January 1995.

[11] “Flags, veils and sharia: Turkey’s future,” The Economist, 19 July 2008.

[12] “Thousands stage new pro-secular rally in Turkey,” Agence France Presse 26 May 2007.

[13] Milliyet, 30 June 2008. See also Gareth Jenkins, “Poll Suggests Weakened but Stable Support for AKP,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, 30 June 2008.

[14] Stephen Kinzer. “State Crimes Shake Turkey as Politicians Face Charges,” The New York Times, 1 January 1998.

[15] “Turkish Islamists aim for power,” Manchester Guardian Weekly, 3 December 1995.

[16] “Ergenekon remains hidden in the shadows,” Turkish Daily News, 17 July 2008.

[17] Yavuz Baydar, “Conspiracies flourish in times of mass psychosis.” Today’s Zaman, 16 June 2007.

[18] Sebnem Arsu, “Thousands March in Turkey at Funeral of Slain Judge,” The New York Times, 18 May 2006.

[19] Today’s Zaman, the daily newspaper of the Islamist Gulen movement, urged prosecutors to dig deeper into links between the Dink assassination and the alleged Ergenekon conspirators. Emine Kart, “Dig deeper into Dink murder-Ergenekon link.” Today’s Zaman, 13 July 2008.

[20] Yusuf Kanli. “Death of the ‘financier of a gang,’ Turkish Daily News, 7 July 2008.

[21] “Ayse Asuman Ozdemir tahliye edildi,” Radikal (Istanbul), 18 July 2008.

[22] See Gareth Jenkins, “Alleged Surveillance of Senior Judges Raises Questions about Politicization of Turkish Police,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, 20 May 2008.

[23] “Opposition says Ergenekon government tool,” Turkish Daily News, 2 July 2008.

[24] “26 detained in new wave Ergenekon arrests,” Turkish Daily News, 24 July 2008.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Email communication with Turkish academic, Istanbul, 12 July 2008.

[27] “Sorguda ilginc sorular,” Hurriyet, 5 July 2008.

[28] “Former generals arrested as Ergenekon leaders,” Turkish Daily News, 7 July 2008.

[29] “Ex-generals, journalists detained in Turkish probe: report,” Agence France Presse, 1 July 2008.

[30] Vakit, 26 May 2008; “Watergate Scenes in Ankara: Who Bugged the CHP?” Turkish Daily News, 29 May 2008.

[31] “Military prosecutor steps into Ergenekon.” Turkish Daily News, 15 July 2008; “Ergenekon indictment accepted,” Turkish Daily News, 26 July 2008.

[32] Ibid.

[33] “Ergenekon indictment accepted,” Turkish Daily News, 26 July 2008.

[34] NTV television, 14 July 2008.

[35] Hasan Karakaya, “Ergenekon-dan Neocon’-lara bir yol gider!” Vakit, 5 July 2008.

[36] Taraf, 26 July 2008.

[37] “A few hours when jeopardy doubled.” Turkish Daily News, 2 July 2008.

[38] Cengiz Candar, “Waking up to Ergenekon,” Turkish Daily News, 3 July 2008.

[39] Ali H. Aslan, “Turkey’s American Prosecutors,” Today’s Zaman, 18 April 2008.

© 2008 Mideast Monitor. All rights reserved.

————————————————————————————————————————————

Who is Michael Rubin?

Michael Rubin, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and an adviser on Iran and Iraq in the Donald Rumsfeld Pentagon, is an outspoken and sometimes controversial proponent of U.S. intervention in the Middle East and other global hotspots. Cited by the Washington Post’s Robin Wright in August 2007 as a leading advocate, along with the likes of neoconservative progenitor Norman Podhoretz, for intervention in Iran, Rubin has repeatedly argued that in order to succeed in Iraq the United States must take on Tehran (Washington Post, August 9, 2007). Arguing in a March 2007 speech at the University of Haifa that ” U.S. and Iranian interests in Iraq are diametrically opposed, and will continue to be until one side wins and the other loses,” Rubin has suggested a number of ways of taking on leaders like Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, including assassination. In an August 28, 2006 National Review article, Rubin wrote: “If a single bullet or bomb could forestall a far bloodier application of force, would it not be irresponsible to fail to consider that option—especially when the leaders of both Iran and North Korea threaten to use nuclear weapons and call for the destruction of both regional democracies and the United States?”

According to his AEI bio page, Rubin’s research areas at the institute include “domestic politics in Iran, Iraq, and Turkey; Kurdish society; and Arab democracy.” A frequent commentator on the state of the Iraq War, Rubin said during a July 24, 2006 AEI discussion on “The Future of Iraqi Armed Forces”: “Many people have looked at the current situation in Iraq as indicative of the failure of democracy. I’d argue that that is unfair and that what it’s really indicative of is the failure of counter-terror policy.”

Along with many of his AEI colleagues—including Michael Ledeen and Danielle Pletka—Rubin has, since his departure from his position in the Bush administration as staff adviser, frequently criticized Bush administration foreign policy for straying from its hardline, non-diplomatic track since the Iraq War began unraveling. In an interview with Time magazine, Rubin argued that efforts to negotiate with Iran would simply bolster the regime’s position: “The very act of sitting down with them recognizes them” (May 22, 2006).

“The cost of any military strike on Iran would be high, although not as high as the cost of the Islamic Republic gaining nuclear weapons,” says Rubin. “The Bush administration is paying the price for more than five years without a cogent, coordinated Iran policy. Each passing day limits policy options. Engaging the regime will preserve the problem, not eliminate it. Only when the regime is accountable to the Iranian people can there be a peaceful solution. To do this requires targeted sanctions—freezing assets and travel bans—on regime officials, coupled with augmented and expedited investment in independent rather than government-licensed civil society, labor unions, and media. It may be too late, but it would be irresponsible not to try” (Wall Street Journal, April 14, 2006).

Rubin cautions that U.S.-government aid shouldn’t go to “reformers” who are working within the system but rather to “the democrats” or “freedom seekers.” In an interview with National Review Online, he said: “Reformists are part and parcel of the regime and do not speak for the democrats” (National Review Online, April 25, 2006).

According to Rubin: “The real threat isn’t that Iran will drop a nuclear weapon on Washington, but rather that with a nuclear deterrent, its leadership will become so overconfident that it will lash out with conventional terrorism.”

In an August 7, 2007 editorial, Rubin took aim at the Bush administration, this time for its dealings with Turkey. Rubin charged that the administration had “flip-flopped” in its dealings with “terrorists,” in this case the Kurdistan Workers Party, which U.S. forces have not targeted despite promises to Turkey to do so. He wrote: ” President George W. Bush’s failure to uphold an assurance to Turkish officials that the United States would take action against the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a terrorist group, is merely the latest in a series of broken promises. Bush has backtracked on both the philosophical underpinnings of his foreign policy as well as individual promises to specific nations and world leaders. The president’s record of broken promises will haunt future administrations and mar Bush’s foreign policy legacy.”

Like many of his neoconservative colleagues, Rubin’s political trajectory began on the left. He highlighted his liberal background in a National Review Online interview, saying: “I’m not just at AEI, neocon, Zionist conspiracy central, but I was also Quaker-educated for 14 years and spent one summer interning for a Democrat on Capitol Hill funded by a Congressional Black Caucus Foundation summer fellowship. Let Mother Jones go nuts with that wire diagram.”

In a May 2004 article titled “You Must be Likud!” published by National Review Online , Rubin criticized the “creeping anti-Semitism in the current discourse,” citing with approval Max Boot’s observation: “If neocons were agents of Likud, they would have advocated an invasion not of Iraq or Afghanistan but of Iran, which Israel considers to be the biggest threat to its security.”

At the start of the second George W. Bush administration, Rubin commended the president for being sincere in his commitment to “freedom, liberty, and democracy.” But “the rank-and-file of not only the CIA but also of the State Department and even many in the Pentagon are hostile to the president’s Middle East policies.” Writing in the Jewish magazine The Forward, Rubin predicted that George W. Bush’s second-term administration would “replicate the mistakes of the first. The State Department will carry the day with a renewed effort to engage, and the Islamic Republic will be just as willing to accede” (The Forward, January 28, 2005).

In April 2006 Rubin, along with other prominent neoconservatives, participated in a smear campaign against respected blogger and University of Michigan professor Juan Cole, who was being considered for a tenured position at Yale, Rubin’s alma mater. Writing in the Yale Daily News, Rubin hinted that Cole’s analysis of the Middle East might be skewed by anti-Semitism. “While Cole condemns anti-Semitism,” wrote Rubin, “he accuses prominent Jewish-American officials of having dual loyalties, a frequent anti-Semitic refrain. That he accuses Jewish Americans of using ‘the Pentagon as Israel’s Gurkha regiment’ is unfortunate” (Yale Daily News, April 18, 2006). On June 1, 2006, Yale’s Senior Appointments Committee announced that it had rejected Cole’s nomination, despite three other committees having already accepted it. Several observers were convinced that the rejection was a direct result of the accusations against Cole. “I’m saddened and distressed by the news,” said John Merriman, a Yale history professor. “I love this place. But I haven’t seen something like this happen at Yale before. In this case, academic integrity clearly has been trumped by politics” (Nation, July 3, 2006).

Rubin’s reputation as a scholar took a hit in early 2006 when the New York Times revealed that he had reviewed propaganda articles that had been produced for distribution to the media by the PR firm Lincoln Group, which had been hired by the Pentagon. According to the Times, Lincoln Group “paid Iraqi newspapers to print positive articles written by American soldiers” (New York Times, January 2, 2006). When first asked a month earlier by the Times about Lincoln’s contract with the Pentagon, Rubin said: “I’m not surprised this goes on. Informational operations are part of any military campaign. Especially in an atmosphere where terrorists and insurgents—replete with oil boom cash—do the same. We need an even playing field, but cannot fight with both hands tied behind our backs” (New York Times, December 1, 2005). What Rubin didn’t mention to the Times in December was that he had given the Lincoln Group feedback on its work. When later asked by the Times about his role in the Lincoln affair, Rubin admitted: “I visited Camp Victory and looked over some of their proposals or products and commented on their ideas. I am not nor have I been an employee of the Lincoln Group. I do not receive a salary from them” (New York Times, January 2, 2006).

According to retired Air Force Lt. Col. Karen Kwiatkowski, who worked briefly in 2002 and 2003 in the Pentagon’s directorate for Near East and South Asian Affairs (NESA), an office overseen by William Luti and whose Iraq desk eventually became the Office of Special Plans, Rubin was one of a number of researchers from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy (WINEP) and other like-minded, pro-Israel think tanks who were brought in to staff the Iraq desk. When she volunteered to take a job in the NESA directorate, writes Kwiatkowski, she “didn’t realize that the expertise on Middle East policy was not only being removed, but was also being exchanged for that from various agenda-bearing think tanks, including the Middle East Media Research Institute, the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, and the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs. Interestingly, the office director billet stayed vacant the whole time I was there. That vacancy and the long-term absence of real regional understanding to inform defense policymakers in the Pentagon explains a great deal about the neoconservative approach on the Middle East and the disastrous mistakes made in Washington and in Iraq in the past two years” (Salon.com, March 10, 2004).

After his stint working for the government, which also included serving briefly as a political adviser to the Coalition Provisional Authority, Rubin returned to the neoconservative think tank community, resuming his associations with AEI, the Middle East Forum, and WINEP. Rubin serves as editor of Middle East Quarterly, which is co-published by the Middle East Forum and the U.S. Committee for a Free Lebanon.

In her War and Piece blog, Laura Rozen wrote that “like Ledeen, Rubin straddles the worlds of government consulting, academic-think tank-dom, and journalism-advocacy on behalf of neocon causes. Rubin has spent the past few years as a consultant to the Pentagon’s Office of Special Plans and then the Office of the Secretary of Defense (read: Doug Feith), and more recently has served as a political adviser to the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq … It will be interesting to see where Rubin’s combination of consulting for neocon officials at the Pentagon, and advocacy on behalf of their pet causes at AEI and in the New Republic and other media, will lead him. He certainly seems to be being carefully groomed for something special over at AEI” (War and Piece, April 24, 2004).

Affiliations

Middle East Forum: Middle East Intelligence Bulletin Editorial Board Member; Iran, Iraq, and Kurdish Expert; Middle East Quarterly, Editor (2004-present)

Middle East Forum Lebanon Study Group: Signatory

American Enterprise Institute: Resident Scholar

Council on Foreign Relations: International Affairs Fellow (2002-2003)

Carnegie Council for Ethics and International Affairs: Fellowship Recipient (2000-2001)

U.S. Committee for a Free Lebanon: Former Golden Circle Member

Leonard Davis Institute for International Relations: Visiting Fellow

Washington Institute for Near East Policy: Soref Fellow (1999-2000)

Yale University: Lecturer (1999-2000)

Hebrew University: Lecturer (2001-2002)

Sulaymani University: (Iraqi Kurdistan) Lecturer (2000-2001)

Salahuddin University: (Iraqi Kurdistan) Lecturer (2000-2001)

Government Service

Office of the Secretary of Defense: Staff Adviser for Iran and Iraq and Member of Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq (2002-2004)

Pentagon Office of Special Plans: Iran/Iraq Adviser (2002-2004)

Education

Yale University: B.S. in biology; M.A. in history; Ph.D. in history

Sources

Robin Wright, “In the Debate Over Iran, More Calls for a Tougher U.S. Stance,” Washington Post, August 9, 2007.

Michael Rubin, “Iranian Strategy in Iraq,” Speech at the University of Haifa, March 13, 2007.

Michael Rubin, “President Bush’s Broken Promises,” American Enterprise Institute, August 7, 2007.

Michael Rubin, “An Arrow in Our Quiver: Why the U.S. Government Should Consider Assassination,” National Review, August 28, 2006.

AEI Discussion, “The Future of the Iraqi Armed Forces,” July 24, 2006.

James Carney, “Why Not Talk?” Time, May 22, 2006.

Michael Rubin, “Nuclear Hostage Crisis,” Wall Street Journal, April 14, 2006.

Q&A with Kathryn Jean Lopez, “Dealing with Iran,” National Review Online, April 25, 2006.

Michael Rubin, “You Must be Likud! Anti-Jewish Rhetoric Infects the West,” National Review Online, May 19, 2004.

Michael Rubin, “Bush Marches into a Second Term,” The Forward, January 28, 2005.

Michael Rubin, “Cole is Poor Choice for Mideast Position,” Yale Daily News, April 18, 2006.

Philip Weiss, “Burning Cole,” The Nation, July 3, 2006.

Jeff Gerth and Scott Shane, “The Struggle for Iraq: The News Media; U.S. Is Said to Pay to Plant Articles in Iraq Papers,” New York Times, December 1, 2005.

David S. Cloud and Jeff Gerth, “Muslim Scholars Were Paid to Aid U.S. Propaganda,” New York Times, January 2, 2006.

Karen Kwiatkowski, “The New Pentagon Papers,” Salon.com, March 10, 2004.

Washington Institute for Near East Policy: Biography: Michael Rubin [Web Archive, June 6, 2002], web.archive.org/web/20020606002155/http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/senior/rubin.htm.

American Enterprise Institute, Scholars & Fellows, Michael Rubin Biography,

www.aei.org/scholars/scholarID.83,filter.all/scholar.asp.