Peddling religion

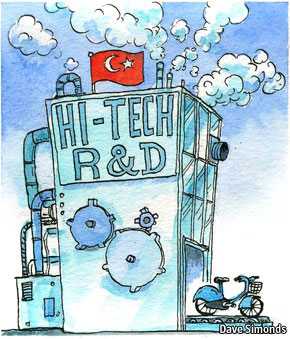

Why secular academics fret about an “Islamic bicycle”

Sep 15th 2012 | ISTANBUL | from the print edition

“A BICYCLE that is produced with God’s blessings in mind and man’s interests at its fore is an Islamic bicycle.” The pronouncement made at a recent conference in Istanbul by Alparslan Acikgenc, a professor from the Yildiz Technical University, brought nods of approval from his colleagues. “A bicycle that is painted with substances harmful to humans cannot be Islamic,” agreed another professor.

“A BICYCLE that is produced with God’s blessings in mind and man’s interests at its fore is an Islamic bicycle.” The pronouncement made at a recent conference in Istanbul by Alparslan Acikgenc, a professor from the Yildiz Technical University, brought nods of approval from his colleagues. “A bicycle that is painted with substances harmful to humans cannot be Islamic,” agreed another professor.

While the exchange elicited a flurry of mirthful commentary, not everyone was amused. Mustafa Akyol, a liberal Muslim writer, called the idea of an Islamic bicycle an “expression of the self-isolating mentality that has stagnated Muslim thought.” Secular academics have long fretted that the mildly Islamist Justice and Development (AK) party, in power since 2002, is promoting Islam ahead of science. They point to the introduction this year of Koran lessons in state-run schools. The emphasis on religious education is part of a controversial overhaul of the national curriculum, which many argue flies in the face of the rigidly secular principles of Kemal Ataturk, Turkey’s founding father. This follows the appointments of overtly pious rectors to various state universities.

“For all their claims of being able to reconcile religion with modernity, Islamic movements in Turkey have signally failed to do so,” argues Ali Alpar, an astrophysicist at Istanbul’s Sabanci University. Mr Alpar is among a group of academics who resigned in protest from the country’s National Academy of Sciences last year after the government announced that it would henceforth be choosing some of its members.

In the event the government decided to let the country’s top science agency, known as TUBITAK, submit some of the names. Mr Alpar and his friends were unswayed. The agency has been steeped in controversy of its own. This erupted when it allegedly forced the editors of its science magazine to kill a cover story on Charles Darwin in March 2009. The move followed tweaks to TUBITAK’s charter that gave the government a greater say over its affairs. The agency later claimed that it had not censored the piece, blaming the change on editorial wrangles. But Mr Alpar says that an article on Galileo that the agency commissioned him to write was also spiked.

Suggestions that AK is steering Turkey towards Islamic rule are overwrought. And as the rest of Europe wrestles with the euro crisis, the Turkish economy continues to grow under AK’s steadying hand. Yet if Turkey is to remain competitive it needs to invest far more in research and development (the Directorate for Religious Affairs, which employs thousands of clerics, was allocated double the amount slated for TUBITAK last year). Alienating the country’s top scientists doesn’t help. “It is time,” says Mr Akyol, “for Muslims to rethink why early Islamic civilisation produced so much of universal value, from algebra to the lute, and why we hardly do that today.”

via Turkey and science: Peddling religion | The Economist.